ANIMATION & PLASTIC ARTS

William Henne

The notion of Plastic Arts is superimposed on that of Visual Arts, which encompasses painting, sculpture, video, photography, comics, digital art and therefore cinema, as opposed to literature and music. The Visual Arts therefore include animated films and animation proper (the distinction between animated films and animation is described in the article ANIMATION, FILM & ANIMATION FILM). The word plastic refers to form.

In formal terms, animation is a hybrid discipline that shares a series of technical, aesthetic and conceptual attributes at work in other disciplines: material, colour, composition, volume, light, drawing, narration, dramaturgy, scenography, movement, rhythm, expressiveness, editing, sound… Like other practices, animation has been constantly reinventing itself since its origins – from its formalisation through pre-film animation devices – emphasising one or other of the aspects listed above.

If we consider that painting, sculpture or photography are petrified places, a space that is a priori immobile, frozen in an instant or a limited duration, animation is a space that shares graphic and chromatic properties with these disciplines, while at the same time deploying this space in time and movement.

We will begin by looking at how other disciplines have used movement in their productions. This will be an opportunity to create possible links with animation. It should be made clear, however, that these examples are not intended to create an antecedent or an origin for animation. If we need to find antecedents to animation, which is indeed a nineteenth-century invention, we can refer to Maurice Bessy’s book, Le mystère de la chambre noire (Pygmalion, 1990).

Secondly, we will give examples of animation that involves plastic properties traditionally attributed to other disciplines, that have been influenced by these disciplines, that refer to them or that have collaborated with them.

Finally, we will look at examples of artists in the field of what is known as modern and contemporary art who have used animation in their work, in continuity with the first part.

Without necessarily going back to the cave paintings with the famous hyperkinetic boar at Altamira (late Upper Palaeolithic, Magdalenian -17,000 to -14,000), let’s start with a famous and iconic painting from the Renaissance. In Sandro Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus (Nascita di Venere) (1486), movement is conveyed by the subject, the appearance of a goddess, by the tense composition and by illusionist devices: all the contorted bodies shift from their centre of gravity within this triangle on the verge of collapse, criss-crossed by motifs that denote the effervescence of the mythological scene and therefore denote its movement: angels’ wings outstretched, a shower of flowers, fabrics and hair blown by the wind, and sea waves stylised by a graphic line rather than a trompe-l’œil rendering (in the manner of a Hockney with his sinuous lines suggesting the undulation of the water in his Californian pools). Finally, there is a discreet graphic sign underlining the breath of the angel with swollen cheeks, heralding the vectorisation discussed below.

Modern artists such as Kandinsky and Mondrian would use these dynamic compositions in a non-figurative register.

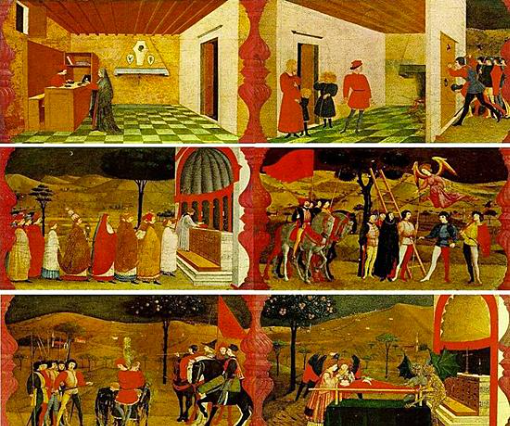

The 6 episodes of The Miracle of the Profaned Host by Paolo Uccello (1467-1468) constitute an overtly narrative sequence that involves, in the ellipses produced between the static images, a series of virtual displacements of the characters left to the viewer’s imagination.

In The Haymaking (De hooioogst) by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1565), the succession of figures at work, or groups of walkers, in a line or side by side, evoke snapshots of the same movement (whereas Vincent van Gogh’s Sunflowers (1888) is more evocative of time, through the different stages of flowering in the same vase). In a way, movement is represented on both a visual and a dramaturgical level, insofar as these decomposed actions assign individuals their social role and their (narrative) function in terms of the division of labour.

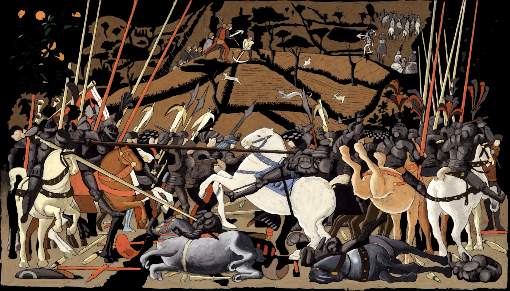

Effects of displacement can be found in Paolo Uccello’s compositions, such as in The Battle of San Romano (1438-1456), where the fanning out of the spears evokes dynamic patterns of death. Generally speaking, a repetitive motif produces an effect of movement, in the gap between recurrence and difference, and is used systematically in certain paintings, figurative or otherwise, in twentieth-century art (Josef Albers, Andy Warhol, Claude Viallat, Roman Opalka, Tarashi Murakami…).

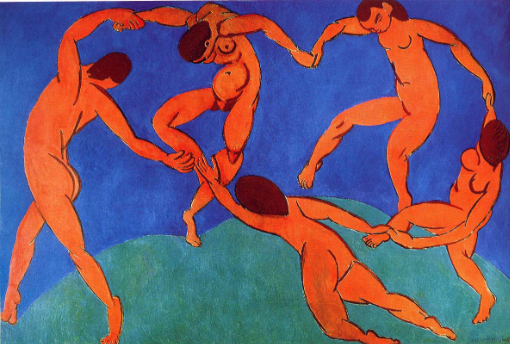

In a similar, more systematic device, Henri Matisse offers a sequence of steps in the joyful round of La danse (1910-1911), whose figures could easily be isolated, seeming to represent the same character, and recombined in a zoetrope or animated gif.

Again in a narrative mode, Claude Monet’s series, such as Meules (1890) or the 28 canvases of Cathédrale de Rouen (1892-1895), depicted at different times of the day, describe the changes in light and weather, and are as much about the expanse of time as the spatial changes in shadows. The narrative ellipses encountered in the Uccello sequence are again present, except that here Monet emphasises the continuity between the images through the systematic persistence of the motif and the single point of view (in reality, Monet chose two different points of view).

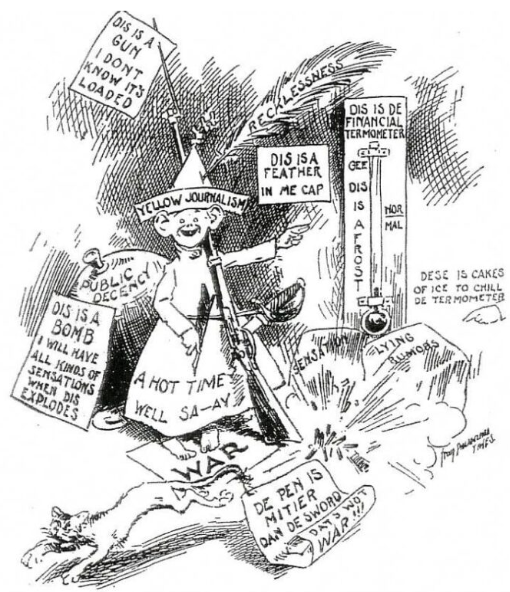

In 1912, Marcel Duchamp presented his Nude Descending the Staircase No. 2, inspired, in the artist’s own words, by the chronophotographs of Étienne-Jules Marey and the photographic studies of Thomas Eakins and Edward Muybridge. Each part of the body of the famous geometric nude describes a range of interpenetrating positions that not only unfold on the canvas, but are also accompanied by multiple sutures and graphic striations that can be likened to conventional codes such as those found in press cartoons or comic strips of the period (such as Richard Felton Outcault’s Yellow kid, 1895).

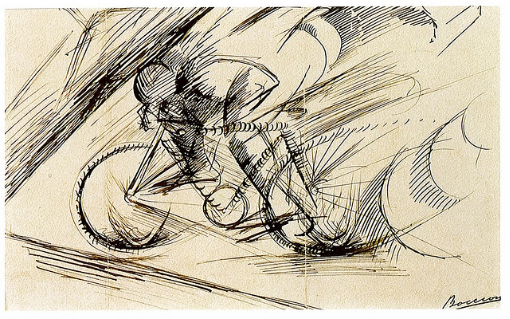

This use of speed strokes, which we call vectorisation and which sometimes merge with the work of hatching, light and shadow, is at work with the Futurists, as in this preparatory drawing by Umberto Boccioni for his Dynamism of a cyclist (1913). Added to this is a factor of expressive distortion. This distortion, this anamorphosed body, dedicated to the glory of modern speed, is in some ways an extension of the figures in tension or imbalance that represented movement in more “realistic” paintings, following the example of Expressionism.

In addition to illusionist, graphic or narrative devices, movement is embodied in the gestural paintings of Jackson Pollock, who was himself influenced by the currents of modern art and painters of the past who liberated the brushstroke, from Rubens to the Fauves, via Rembrandt and the Impressionists to Roberto Matta. But in Pollock’s interlacing paintings, the movement is latent, a result of the spectator’s projection into the painter’s gesture, either through a transfer of affect, a form of empathy, provided the spectator agrees, or through a cerebral approach that conceptually reconstitutes, in the traces of paint, the act that generated it.

And for the sake of completeness, even if it takes us somewhat away from the subject, a final type of movement is at work in an image, in a multi-frame or a polyptych: that of the viewer’s gaze on the canvas. By playing on the depth of landscapes, on perspective and vanishing lines, on narrative, on contrasts of colour and light, we organise a circulation of the gaze that is no less a movement.

Sculpture uses the same illusionist, graphic and narrative processes as painting. From the outset, it has sought to represent movement. In Hellenistic sculpture, a work like The Victory of Samothrace depicts the breath of air in the folds of the drapery, and suggests imminent flight thanks to the outstretched wings and supported right leg. A promise of movement that contradicts the consistency of the marble.

More interesting is the thesis of Georges Sifianos, who worked for years on the Parthenon Frieze. Using a cautious and justified form of anachronism, he sees, among other things, in this bas-relief, in certain variations of figures, logics that can be compared to animation (the thesis encompasses, moreover, multiple issues in aesthetic, ideological and moral terms, we refer you to the work of Sifianos).

As in painting, deformation is also exercised in volume, as in Umberto Boccioni’s Forme uniche della continuità nello spazio (1913), to take an example from the Futurists, generating the same paradoxical tension between dynamism and material as in classical sculpture.

But modern art was not limited to these illusionist or expressive effects. Having largely discarded illusionism, proponents of modern art created sculptures that physically engaged movement, such as Alexander Calder’s or Pol Bury’s kinetic sculptures.

There are probably paintings that have used mechanical, electrical or electronic principles to physically set in motion motifs on the canvas, placing his works on the borderline between installation, sculpture and video art. Modernity has also consisted in overturning categories, and this article is part of that process of crossing and bridging disciplines, underlining the inevitable porosity between them.

Photography illustrated the movement just a few years after its advent. By its very nature, the simple act of freezing movement produces effects similar to the illusionism of painting and statuary; it presupposes a before and an after. Because a priori this moment has really existed, it is a Ça-a-été, to quote Roland Barthes. From then on, in this relationship with the ‘ reality ‘, the photograph encourages the viewer to extrapolate the moment he or she is contemplating.

We have already mentioned Étienne-Jules Marey, Edward Muybridge and Thomas Eakins. In Muybridge’s case, movement was rendered by a sequence obtained using several cameras, whereas Marey’s Chronophotography technique consisted of taking a series of snapshots on a single fixed glass plate coated with gelatin-bromide, using a single camera equipped with a single lens, placed in a mobile photographic chamber.

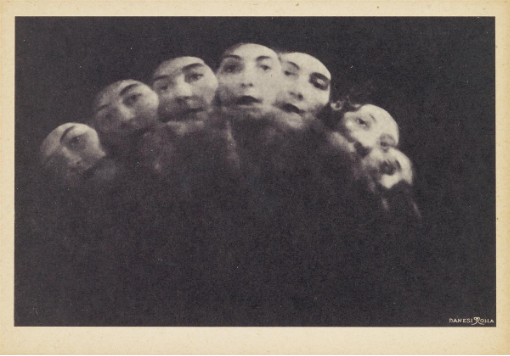

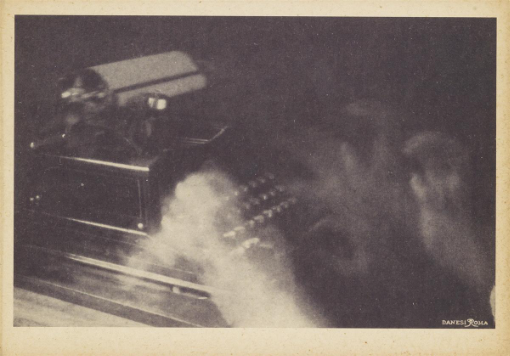

In his work on photodynamics, published in the form of 6 postcards in the years 1911-1913, the Futurist artist Anton Giulio Bragaglia used multiple exposure to depict an action, just as he used a long exposure time to capture both the stages of a movement (a modern movement, in this case associated with a (type)machine), but also a ghostly rendering that seems to give information about the different speeds of each hand at the moment they are printed on the film, as well as a motion blur (the sharper the hand, the slower it is, and vice versa). Motion blur can be a figure that decomposes and fades in front of a sharp background, as in Bragaglia’s photo, but it can also materialise as a figure against a blurred background, when the camera follows the moving subject.

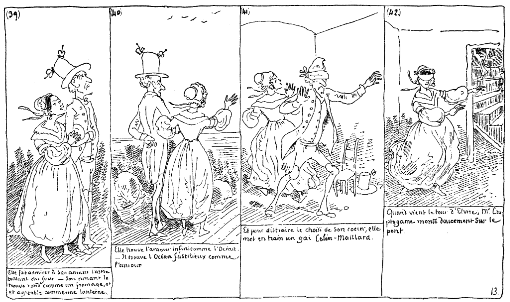

The comic strip is an art of duration, inscribed within the images (which can concentrate different actions, figures or places in the same space), between the images and their sequential logic, between the texts and between the pages, suggesting multiple articulations, to use Thierry Groensteen’s terminology (arthrology), in a continuous and discontinuous way, but also at distant moments in the book (below Histoire de Monsieur Cryptogame by Rodolphe Töpffer, 1830). We will refrain from making an inventory here of the operations that generate movement in comics, as the scope of this field of study can reach heights of sophistication that take us far from our subject.

A grotesque scene from Hergé’s The Crab with the Golden Claws (1941), one of the author’s favourite panels, is quoted too often but cannot be ignored. It lists, to use animation jargon, the key poses of the berabers on the run from Captain Haddock’s fire of insults.

It’s a process that Cyril Pedrosa, who comes from an animation background, uses systematically in L’âge d’or (2018), where he uses different poses for the same character.

These processes also refer to the choice that the draughtsman makes in representing a movement in a single pose, by selecting the moment that best expresses it. For example, the beginning and end of a movement will often be more meaningful and expressive than an intermediate pose.

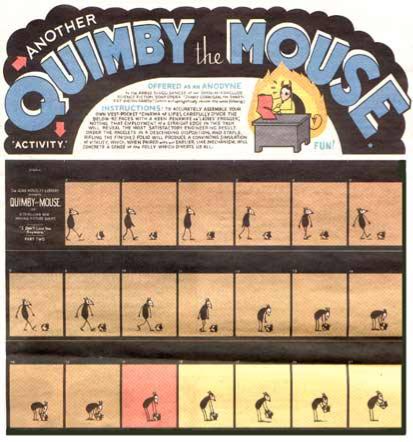

Pedrosa does not refer explicitly to animation, which is not the case with Chris Ware’s Quimbie the mouse (1993-2003).

Comics embody the notion of vectorisation par excellence, inventing a host of graphic signs, culminating in their use in manga, as in these plates by Osamu Tezuka and Yuichi Yokoyama, where onomatopoeia itself becomes a vector of movement (see art historian Ryan Holmberg’s study of speed lines in manga, published in issue 9 of La Crypte Tonique’s magazine, L’œil sur les rails, 2013).

In a book devoted to manga, Thierry Groensteen points out that the breakdown of actions in manga and the economy of drawings in anime (Japanese animation) curiously tend to converge.

Then there’s the question of movement in cinema. The second notion seems to cover the first: cinema is time, and it is movement, if only through the sequence of images, to which are added processes that reinforce the illusion of movement such as editing (cuts, splices, discontinuities, jumps of axis, etc.), camera movements (panning, travelling, zooming, changes of focal length, steadycam, etc.), variations in depth of field, special effects (speedlines, blur, vectorisation, etc.), lighting (contrast, shadow, stroboscopic effect, etc.), playback speed (slow motion, fast motion), sound (sound effects, off-screen, music, sound effects) and, of course, acting. It differs from animated film in that it records images mechanically, in an exogenous way, whereas animation takes a more analytical approach and chooses what it stages.

ART IN ANIMATION

Let there be no mistake about the title of this chapter: animation is indeed a visual art. As stated in the introduction, we are talking here about the presence of other visual arts in animation, as much by the simple fact that they share common properties as by the interplay of references, influences and quotations.

Animation is an interdisciplinary field (drawing, colour, set design, dramaturgy, sound, etc.) and naturally calls on other disciplines, including those outside the visual arts such as music and literature.

The phenakistiscope, zoetrope, thaumatrope, praxinoscope and other optical games of pre-cinema spontaneously took over drawing: simple, practical, inexpensive, didactic and, above all, high in contrast, making it easy to perceive shapes that move quickly through devices that do not make them easy to read (slits, mirrors, rods, etc.).

This pre-eminence of drawing was to last throughout the history of animation, for technical reasons – these drawn optical games laid the foundations for traditional animation and drawing is less expensive than volume – but also for cultural reasons, linked to the emergence of press cartoons, caricatures and comic strips in the 19th century.

The inventors of animated cartoons, Émile Cohl (Fantasmagorie, 1908, vimeo.com/16526021) and Winsor McCay (Little Nemo, 1911, vimeo.com/175922680), were originally cartoonists.

In the XXth century, the drawing becomes the integrating and normative tool that sets the standards for the animation industry.

Animation was to accompany the various trends that marked the 20th century, meeting the formal challenges posed by painting, sculpture, engraving, photography, film and even architecture: In the examples that follow, we insist on this notion of accompaniment, whatever the influence that artistic currents may have had on them, because these films are so contemporary with the plastic research of other disciplines. And what’s more, these formal inventions more often than not stem from the very properties of the support and the specific tools used.

To make Lichtspiel Opus 1 (1921, vimeo.com/262027844), Walter Ruttman, who had patented his process, painted simple, plain shapes in oil on glass plates, which he transformed frame by frame by erasing and reshaping the silhouettes on coloured backgrounds. Max Butting’s three-part sonata, which supports the film, does not follow the progression of the figures; it is a simple sound accompaniment. The material appears from time to time in contours, gradations, discreet blends and barely faded traces on the glass. The film, which premiered on 27 April 1921 in Berlin, is considered to be the first non-figurative film in the history of cinema.

In 1920, the Russian architect and painter Naum Gabo used the word constructivism in the Realist Manifesto, considered to be the manifesto of this movement which, since 1917, had focused on simple, rigorous geometric compositions and which was equally at home in architecture, theatre, dance and painting.

In Rhythmus 21 de Hans Richter (1921, vimeo.com/227255950), orthogonal, square or rectangular shapes appear, grow, shrink, superimpose and echo the projection screen, playing with its dimensions, limits, geometry, margins and multi-axial symmetry, while at the same time working with time (hence the polysemous title: it is as much a graphic rhythm as a musical rhythm – even though the film is silent).

A few years earlier, in 1915, Suprematism gave a similar solution, attesting to the two-dimensionality of its medium.

n 1921, the Swedish painter and film-maker Viking Eggeling began creating the 6,720 images, using cut-out paper and aluminium figures, that would make up his Diagonal Symphony (Diagonalsymfonin, 1923, vimeo.com/576389010), a silent symphony of white geometric shapes on a black background shot in the UFA studios in Berlin, a first version of which was screened publicly for the first time in 1922 at the VDI in Berlin and which was shown in its finished form in 1925 at the first international exhibition of avant-garde films at the UFA’s Kurfürstendamm theatre in Berlin. As the only original copy was lost in the Berlin bombings, a reconstruction (which does not present itself as such) was made in the 1940s on the initiative of Hans Richter, based on Eggeling’s preserved rolls. Although not very faithful to the original work in its construction and rhythm, this is the version broadcast today.

The pin screen used by Claire Parker and Alexander Alexeieff, for example in Une nuit sur le mont chauve (1933, vimeo.com/664290584), is a process that plays specifically with light, like the light that prints the film. This vertical white screen is perforated with hundreds of thousands of holes, each with a retractable pin through it, and is lit from the side. We might be tempted to draw a parallel with pointillism, because the image is made up of these multiple pinpoints, but in practice the animator pushes (and pushes back in the other direction), with varying degrees of intensity, sets of pins with his tools, objects of various shapes, which is closer to modelling the material as in a bas relief. The pins cast shadows that vary in length depending on how far they are pushed in, creating a range of gradations from black to white, and giving the animated image the velvety, woven look of an etching or charcoal drawing.

In An optical poem (1938, vimeo.com/133071705), Oskar Fischinger animates two-dimensional geometric shapes made of cut paper on a multi-planar title-board, varying the scales by substitution. The shapes sink, emerge, accumulate, respond to each other, dance to the rhythm of Franz Liszt’s Second Hungarian Rhapsody and describe a cosmological field in constant transformation, torn between a flat space, a layered space and a deep space.

Norman McLaren’s Fiddle-de-dee (1947, onf.ca/film/fiddle_de_dee_fr) is the quintessential example of a form of expression born of the very material that constitutes it. McLaren draws, triturates, smears, paints, streaks and scratches the film itself, generating translucent, dancing layers of random matter and colour, echoing the frenzied, joyful violin of the song Listen to the Mocking Bird.

The same is true of the film Free radicals Len Lye (1958-1979, vimeo.com/341712243), scratched onto 16mm film with needles.

In 70 (1970, vimeo.com/792168779), Robert Breer continued his non-figurative experiments begun in the early 1950s. Lines, shapes, colour and matter intertwine to produce a suffocating, hypnotic stroboscopic effect.

Jan Švankmajer was a member of the Prague Surrealist Group (or Group of Surrealists in Czechoslovakia), which was founded in 1934 and continued until the 21st century. He joined the movement in 1970. In his films, viewers will find all the features of this artistic movement: the dreamlike, the unusual, psychoanalysis, the absurd, collage, etc. The possibilities of dialogue (Dialog vĕcný, 1982, vimeo.com/12073562) makes explicit reference, in its first part, to the composite portraits by the 16th-century Italian Mannerist painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo. Švankmajer takes advantage of the transformative power of animation to orchestrate these cruel and destructive encounters between faces composed of different categories of materials, ultimately resulting in uniform, homogenised figures.

In the feature-length volume film Krysař (Le joueur de flûte, 1986, vimeo.com/192649758), Jiří Barta adapts the German tale in a style that is resolutely inspired by German Expressionism, while also making reference to medieval bas-reliefs and medieval painting on wood. To contrast with these unstructured characters and settings carved in wood, Barta uses real rats, which become more alive than humans.

anadian-American director Caroline Leaf made her first film in her final year at Harvard University, animating sand on a light table (Sand or Peter and the Wolf, 1969). She quickly switched to animated painting for her second film, and won an Oscar for best animated short for her fifth film, The street (1976, onf.ca/film/rue). His visual work is rooted in the tradition of painting: transparency, touch, matter, colour, light, modelling, reserve, flat space. Leaf takes advantage of this moving material to produce fluid, textured transitions, not only between scenes, but also between actions, with a number of plastic discoveries, as in this example cited by Georges Sifianos: another example that shows a state of mind through a gesture that would be impossible to perform using any other medium: the dying grandmother tries to kiss her grandson, who doesn’t want to. The boy’s desire to escape is shown by his left arm slipping out and becoming his right arm before freeing itself from the grandmother’s grasp. This sleight of hand is only possible by blurring the shapes in the paint. The moving painting literally becomes a narrative, conveying the psychology of the characters.

As a link to an earlier example, let’s mention his film Two sisters (1990, vimeo.com/29399991), made by scratching the black emulsion of exposed 70mm colour film. Leaf’s work in reserve and the modelling he produces are inevitably reminiscent of engraving.

Stylistically, and without Leaf making any explicit reference to particular artists or paintings, Chagall and Nolde come to mind.

Swiss filmmaker Georges Schwizgebel also maintains a link with painting, but in a dual relationship. His films are shot through with references to cinema, music, literature and painting. Painting is invoked in the technique used, acrylic and gouache on cellulo, but also through his quotations from Johannes Vermeer, Édouard Manet, Diego Velasquez, Henri Matisse, Giorgio De Chirico, Georges Braques or even Paolo Ucello in The Battle of San Romano (2017, vimeo.com/656704401) where the director sweeps the canvas in a circular fashion and deconstructs the forms in a series of incessant transformations.

In itself, photography has an obvious technical link with animated film through the sensometric (response to light of a sensitive surface such as a photographic plate, for example) and mechanical process. Today, the images that are captured on a Rostrum camera, or in volume animation, pixilation for example, are captured using a camera that generates sequences of images in the same way as the film used in old cameras. Here, animation, film and photography are closely linked and raise shared aesthetic questions.

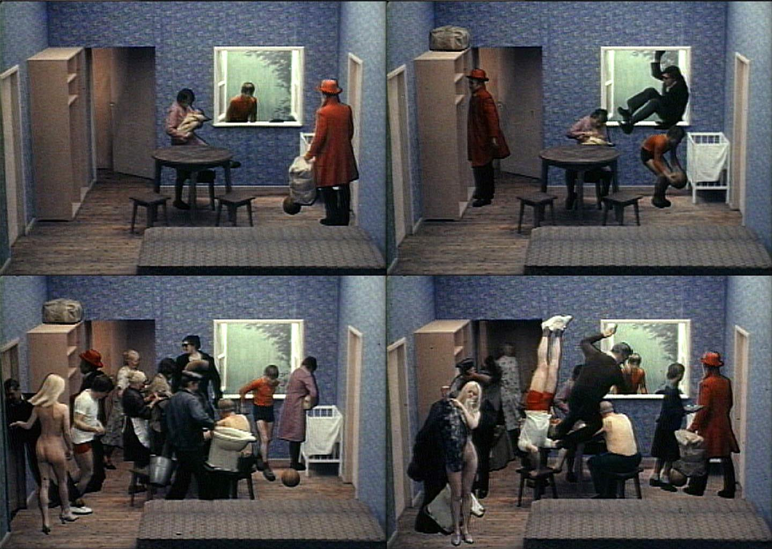

Photography can be used as material, in the manner of a collage, in a film such as Tango by Zbigniew Rybczynski (1981, vimeo.com/38580206), which breaks down the movement cycles of 26 actors into 22 photographic sequences that he cuts out, recombines and re-photographs on his set. The characters gradually invade the space, repeating the same action until the space is saturated, the director’s virtuosity consisting in never making them collide. Tango’s photographic collage also echoes the cohabitation of different individuals who act according to their own logic without taking others into account, like the couple making love on the bed. It’s a paradox: the collage seamlessly integrates the different actions in an illusionistic way, but the actions are indifferent to each other. Later, as techniques evolved, Rybczynski would use video overlay effects, foreshadowing what would come with compositing software.

More simply, photos are used in cut-out paper animations such as Stéphane Aubier’s Les Baltus au cirque (1998, dai.ly/xeyjb)…

… or in mixed media films combining cartoons and photographic sets, such as Ralph Bakshi’s Cooskin (1974, vimeo.com/159504835)…

… or in L’architecte de Geneviève Antoine, Jacques Faton et Patrick Theunen (1987, vimeo.com/122619982) which also both mix live action shots. The drawn characters are anchored in reality, the better to confront it.

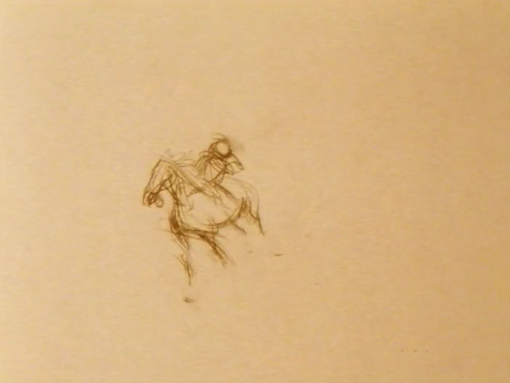

Animated films share the same visual storytelling techniques (direction, dramaturgy, framing, point of view, editing, sound, etc.) as live-action films. Very often, animated films refer to cinema by parodying and boxing up its visual and narrative codes, as in Philippe Capart’s Dead end town (1996, vimeo.com/244274601), which plays so much on Western stereotypes that the film takes the liberty of showing us all the scenes literally in reverse, including the sound, with a suggestive drawing barely sketched in pencil, to the point where certain photograms are totally cryptic (the action is only revealed by the animated movement).

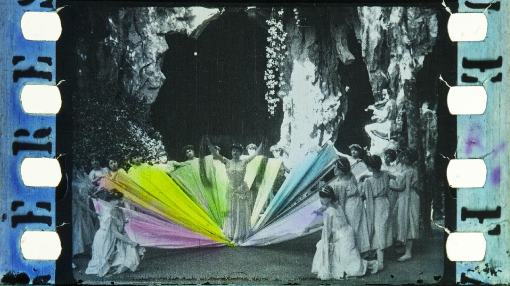

Cinema, on the other hand, uses animation for its special effects, starting with one of the first colouring processes where small hands were used to tint the transparent emulsion frame by frame, before other mechanical, but still laborious, processes took over, such as the stencil technique. This produces a pictorial vibration in the image that can be found in experimental short films and animated painting.

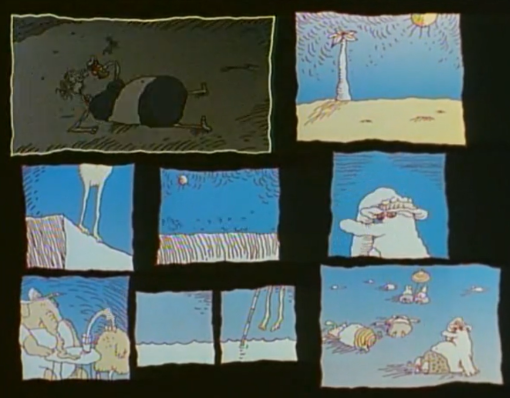

What about comics in animation, apart from the countless adaptations for the screen? Is Paul Driessen’s use of split-screen space reminiscent of a comic strip (The end of the world in four seasons, 1995, vimeo.com/10137093)? It’s not certain. The logics of movement, of entering and leaving the screen, the temporality of the action is not comparable to the usual sequentiality of comics (even if linearity has been overturned a lot in the history of comics).

Links between the two disciplines can be established in this film through certain modes of operation between the images, but there is nothing to indicate that Driessen was thinking of the comic strip when he conceived his device rather than the polyvision of Abel Gance’s Napoleon (1927).

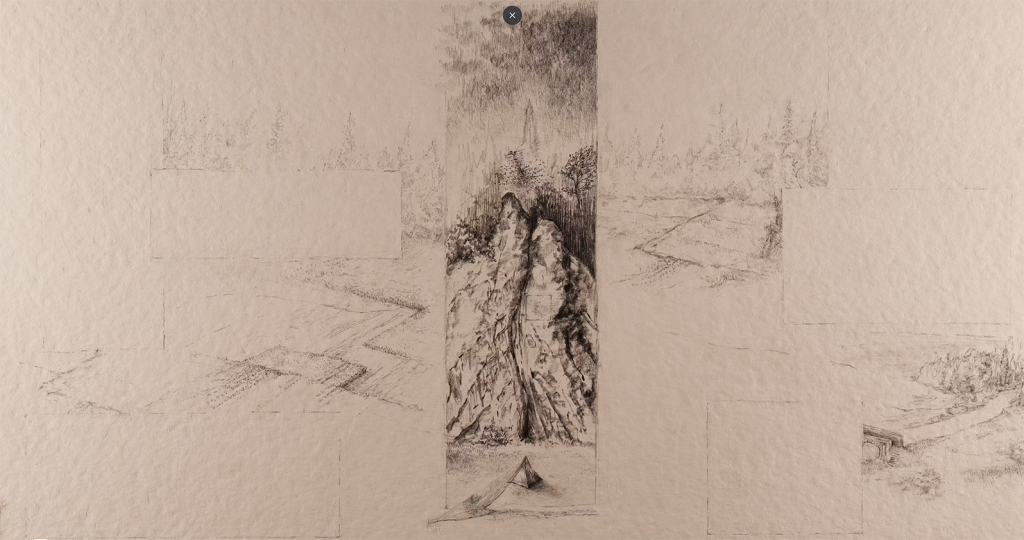

In 2024, Belgian director Nicolas Piret made the experimental short film Silent panorama (vimeo.com/zorobabel/silent-teaser), using graphite pencil to draw the stages of the animated movement directly under the camera, erasing the previous phase of the movement at each frame. The process of animation is made sensitive on screen by the very perceptible texture of the pencil on the granulated paper, mingled with the repentance and successive erasures. The entire film is shot on a single sheet of drawing paper. Piret refers explicitly to the composition of a comic strip by creating a space with sub-frames. This singular unfolding of narrative space in cinematographic space, each sub-frame offering a development of the action or a descriptive insight into an element of the setting, could potentially be extended indefinitely.

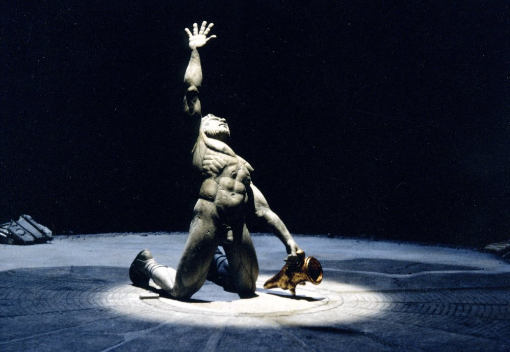

We can’t resist leaving our subject – the visual arts – for a moment to look at the performing arts (theatre, mime, dance, opera, music) through the films made by the British director Barry Purves (Next: the infinite variety show (1989), Screen Play (1992), Rigoletto (1993), Achilles (1995), Gilbert and Sullivan: the very models (1998)), who rethought the stage space in each of his animated puppet films by taking advantage of the transformational possibilities of animation.

This diversion via the performing arts is not innocent, and we’ll come back to it in the conclusions.

CONTEMPORARY ART AND ANIMATION

In no way do the links we are going to establish between animation and what is known as contemporary art constitute an attempt to legitimise animation by lumping it in with the historically more legitimate arts. We believe that animation has, from the very beginning, proved its full legitimacy, and that in itself, one artistic discipline is not fundamentally more artistic than another – it all depends on what you do with it. So we have no pretension of wanting to debunk old prejudices that still confine animation to the sphere of children’s entertainment, let the ignorant wade in their prejudices. Finally, the question of the legitimacy of a discipline is not a real issue for us, we don’t need the validation of our contemporaries to know the value of a discipline.

After all, the question of animation in contemporary art is perhaps only a question of location. As soon as an animation is exhibited in a gallery or museum, its status changes and it falls into the field of contemporary art. This is how Jan Švankmajer’s The Possibilities of Dialogue (1982) came to be exhibited at the Tate Modern in London.

Let’s look at a few examples where animation is used as the main technique in certain works of contemporary art.

Une seconde d’éternité (d’après une idée de Charles Baudelaire) (1971) is an installation by the Belgian artist Marcel Broodthaers, who presents the world’s shortest film, entitled La signature or Ma signature. It shows a loop of the artist’s initials, MB, being written in twenty-four images. Broodthaers ironises the notion of an artist’s film by depicting the emblem of an artist’s (narcissistic) identity, his signature (and its market value). Broodthaers writes: “For Narcissus, one second is already the time of eternity. Narcissus has always respected the time of 1/24th of a second. For Narcissus, the retinal image lasts forever. Narcissus is the inventor of cinema“. Animation is used here in its simplest form, like the drawing itself: a loop of sketchy drawings in the manner of pre-cinema animated cycles.

In works such as Felix in exile (1994, vimeo.com/66485044), which is part of the Guggenheim Museum collection, and History of the main complaint (1996, vimeo.com/434807183), William Kentridge explores historical and political themes linked to apartheid, as well as autobiographical concerns. He uses charcoal animation, erasing part of the drawing from a film shot and modifying the moving parts frame by frame, leaving evanescent traces of the previous stages of drawing.

Kentridge is a jack-of-all-trades: actor, director, draughtsman, engraver, sculptor, painter, tapestry-maker, animator and film-maker, all of which he happily combines in his productions for theatre and opera.

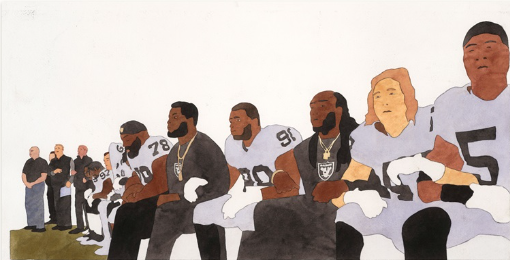

The German-Japanese artist Kota Ezawa uses highly stylised vector animations to recreate historical and cultural events from video sequences, such as the three minutes of The Simpson Verdict (2002), which is part of MoMA’s permanent collection.

He also creates watercolour faux fixes of news photos.

Ezawa aims to create an archaeology of various media moments in the face of the flood of images that invade us.

Digital animation is at the heart of the work of American artist Takeshi Murata, as in Melter 2 (2003, static-files.rhizome.org/Q2839), a set of generative, non-figurative and colourful compositions projected in November 2012 onto the 15 video panels in Times Square.

Japanese artist Tabaimo creates immersive installations based on traditional cartoon sequences, exploring themes such as isolation, urbanisation, gender and the relationship between public and private space, as in public conVENience (2006, youtu.be/UbpAt5nafA4), an animation projected onto the entire wall. The choice of animation, rather than the live action traditionally used in video installations, comes simply from the fact that she uses drawing in all the rest of her work. This gives her control over all the parameters of the image, such as texture, temporality and references to the colours of Ukiyo-e, a Japanese artistic movement from the Edo period. She is also keen to maintain a clumsy style in her drawings – what is sometimes called bad drawing – which turns out to be very expressive: “When my clumsy drawings move, it produces unexpected effects“. Finally, this also gives her complete freedom in terms of staging: vignetting, stroboscopic effects, variations in scale, surreal, fantastic and unusual scenes… She believes that the work is only complete thanks to the viewer’s interpretation.

British artist Julian Opie uses a computer to animate highly stylised characters, verging on the pictographic, with a paradoxically naturalistic movement. His pedestrian walks, like those in Walking on O’Connell Street (2008, youtu.be/Lk2u6xilJNQ), are shown in public spaces.

In Village (2020, vimeo.com/413593321), a 3D animation takes us on a monotonous hour-long stroll through the streets of uniform houses, set to music by Max Richter. Opie came up with the animation after being struck by the labyrinthine street network of a small town in south-west France.

The Italian graffiti and video artist Blu is best known for his film Muto (2009, vimeo.com/993998) , a short film shot in Buenos Aires and Baden in 2008, which features a series of animated murals that move from place to place.

The artist Shahzia Sikander, born in 1969 in Pakistan, presented her first immersive installation Parallax in 2013, with music and sound by the composer Du Yun, a 15-minute animation constructed from hundreds of drawings and paintings, in which abstract, figurative and textual forms coexist and jostle with each other. (vimeo.com/160354141).

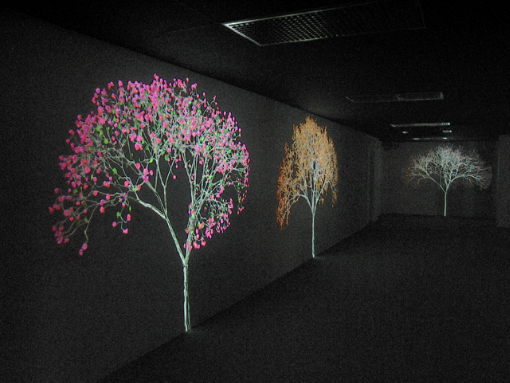

This type of immersive animated installation is comparable to the work of American artist Jennifer Steinkamp, as in Mike Kelley Mike Kelley (2007, vimeo.com/691448232), which shows digitally created trees moved by the wind and changing with the seasons.

Canadian artist Jon Rafman explores the virtual worlds of video game culture in A Man Digging (2013, vimeo.com/67294179).

To return to our introductory remark, with the example of Svankmajer, on the fact that the question of the place of presentation and the context of exhibition is perhaps decisive in the inclusion of an animation in the field of contemporary art, we can note that certain artists show their work both in galleries and at festivals, such as William Kentridge or Richard Negre. Where appropriate, the format of the work is adapted to screen projection. Of course, some animations only make sense in the context for which they are intended, such as Tabaimo’s animated sequences on the three walls of an exhibition room, or Julian Opie’s walking figures placed in public spaces.

We might ask, for example, how Kota Ezawa’s animations about historical events or current affairs differ substantially from an animated documentary: if we leave out the broadcasting context, the boundary is imperceptible.

This exercise in comparison between different disciplines challenges the categories of art: visual arts, performing arts, contemporary art, street art… These categories help us to think about the practices they encompass, and we use them for the sake of convenience and consensus. But we have to recognise that, in practice and in usage, they all interpenetrate.

Kentridge brings animation to the stage, while Purves brings the stage to his animated films.

Artists use animation for a variety of reasons, sometimes because it is simply part of their artistic background, an integral part of their practice (Kentridge, Negre, Tabaimo…), sometimes because it provides them the expressive, graphic and conceptual resources they need for their creative endeavours (Broodthaers, Opie, Blu, Steinkamp, Rafman…).