WRITING ANIMATION: OLGA & PRIIT PARN PART I

William Henne: Can you give a brief description of your career?

Priit Pärn: I was born in 1946 in Tallinn and grew up in a small town with a Soviet military base and I studied biology in Tartu University from which I graduated in 1970. During these studies, from 1968, I regularly drew caricatures for newspapers which constituted my artistic background. I was a caricaturist for a certain time. After University I moved to Tallinn and I worked six years as a plant ecologist. I made designs for 3 animated films from Tallinnfilm Studio. I then changed career in 1976, I went to Tallinnfilm Studio and started my career as an animated film director and artist. I made my first film in 1977, Is the Earth round? [Kas maakera on ümmargune?, 1977].

Is the Earth round? (Kas maakera on ümmargune?, 1977)

But I continued to draw caricatures and started illustrating books, and writing some books, which I still do, one of my favourite hobbies. I more or less stopped caricature in the end of the 80s and I started to make graphic arts, etching, etc. I discovered large-format charcoal drawing. I had many exhibitions – more than 30 – around Europe. In 94 the Finnish Film School, which was teaching live-action film, invited me to teach during one semester. Then I was invited to Turku, Finland. They wanted me to create an animation department at Turku art Academy and I teached during 13 years in Turku. I was still living in Estonia and every month I went for one week.

In 2003 the school received a prize for the best animation School in the world in Ottawa Festival. We had just 12 finished students in our school. We even beat the Royal College of Art.

In 2006 I was invited to create an animation department in Tallinn in Estonia. In 2007 I stopped teaching in Turku and I taught International Bachelor’s (in Estonian) and Master’s courses in English at the Estonian Academy of Arts until 2019. Our students collected more than 140 prizes in international festivals.

Olga joined the team in 2007.

Olga Pärn: Priit became so important in Finland because of his film Breakfast on the grass [Eine murul, 1987] won the Grand Prix in Tampere short film festival in 1988, which was such a big breakthrough for Estonian animation.

Breakfast on the grass (Eine murul, 1987)

Priit Pärn: It was still soviet time but step by step it was going to be crushed to pieces and Breakfast on the grass was for me a film to say goodbye to soviet union. It was unexpectable for Finnish people. I gave interviews for three days.

Georges Sifianos: What was censorship like at the time? Were films allowed to be shown or were they subject to restrictions?

PP: To make a film you need money. The money cam from the state. There was a very tough control. First I wrote a script that had to go through different levels of decision-making. First at the studio level, then at Estonian level, which gave the green light to go to Moscow, where important people decided whether or not the film would be financed, or whether something had to be changed.

When the film is ready, you have to show it here and there. The worst outcome is that they don’t allow the film to be shown anywhere. They put it in a safe and say goodbye. The best outcome is that they accept. Then I don’t know how many millions of people would see it if it were broadcast on all Soviet television channels. Sometimes the film leaves the Soviet Union to be shown at international festivals. For my first film, Is The Earth Round?, in Moscow they have been shocked mainly about the graphic style, saying that it’s not animation but they gave a permission to show it in Estonia but not outside.

Is the Earth round? (Kas maakera on ümmargune?, 1977)

If something was forbidden, it was a very important thing for soviet animators to see this film, because it suppose to be something fresh and surprising. To get money and make my first three films, I showed very different scripts which have been very different from film what I then made. which was risky if they caught me. It would be my last film. But I was lucky. In 1982 I made The triangle [Kolmnurk, 1982]. It was a scandal and they told me I had to cut eight minutes from a 16-minute film. I said I wouldn’t do that.

The triangle (Kolmnurk, 1982)

They had very strange rules: if they caught me while we were still working on the film, they’d stop production and change the director. But if the film was ready, nobody else would come along with scissors to cut out any part of it. I said that I don’t care. Working is just a pleasure to work. For the studio it was important to have money for the next film. There was almost half a year of negotiation with Moscow and we finally made a compromise. So I cut out two seconds and they never send the film outside of the soviet union. I think that in this period The triangle would maybe be shocking for the animation world. They finally showed it on soviet TV and some soviet festivals.

The triangle (Kolmnurk, 1982)

OP: The triangle is a legend for Soviet animators. It was shown before a feature film in the cinemas in Kiev. When Igor Kovalyov saw the film, he went away straight after, bought a new ticket and came back to watch it again. Igor made the film Hen, his wife with a similar drawing style. This changed the world of illustrations and printed graphics.

Hen, his wife, Igor Kovalyov, 1990

PP: After The triangle I knew that it couldn’t work anymore. In 1983 I wrote the script of Breakfast on the grass [Eine murul, 1987] exactly the way the was finally made. But in 1983 Moscow said that such a film would never be made in the Soviet Union. We tried again a year later, changing only the title. They recognised the project and rejected it again. So I started to work as a graphic artist.

Priit Pärn Illustration for the book Päässa tuulee ja ajatuksia sataa, Jukka Parkkinen, Markku Haapio, WSOY, 1992

In 1986, during Perestroika, under Gorbachov, some key people were changed in the main Soviet film department. We sent the project again, there was a long silence and we finally received the message that it was a very good script and that they have been waiting a long time for something like this. The film was finished in 1987 and when we showed this film they took it and sent it to festivals. Most of the people watching the film in the screening room had been working there for 20 or more years. And, if you remember at the end of the film, the inside and outside of the building are identical to those of the building where we screened our film and where these fat ladies were also in reality.

Finally Breakfast on the grass was sent to many festivals.

Breakfast on the grass (Eine murul, 1987)

Zepe: There were also commissions for film and press cartoons in Portugal, but I imagine they were more ignorant and disorganized.

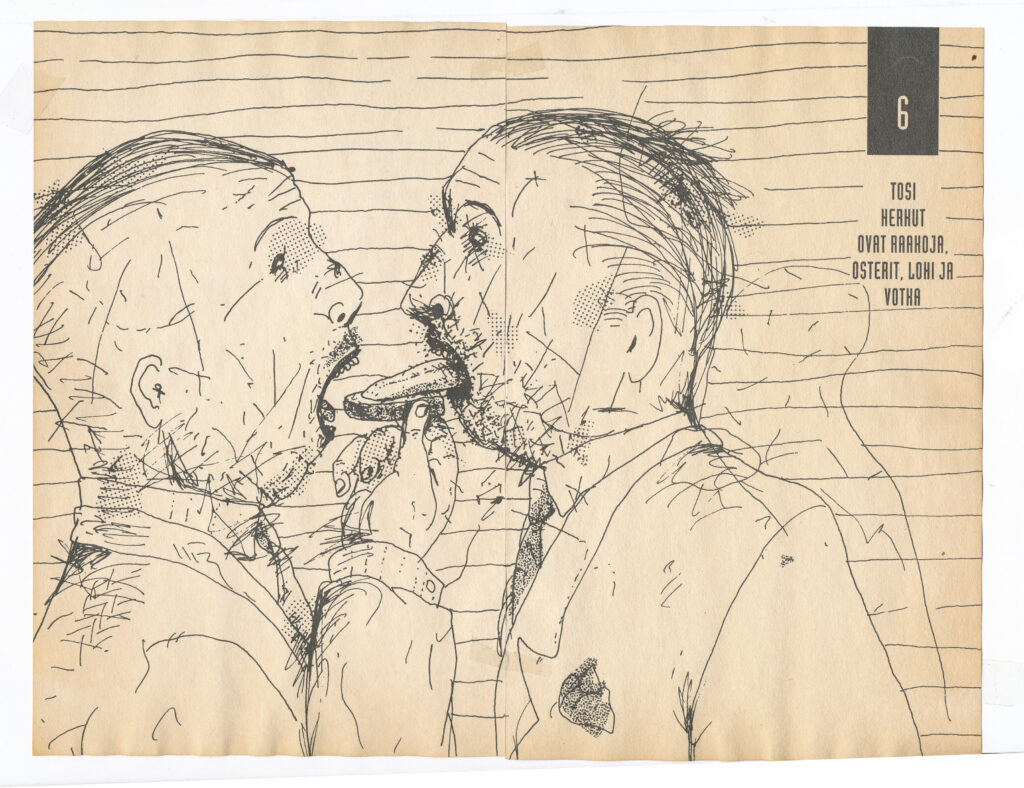

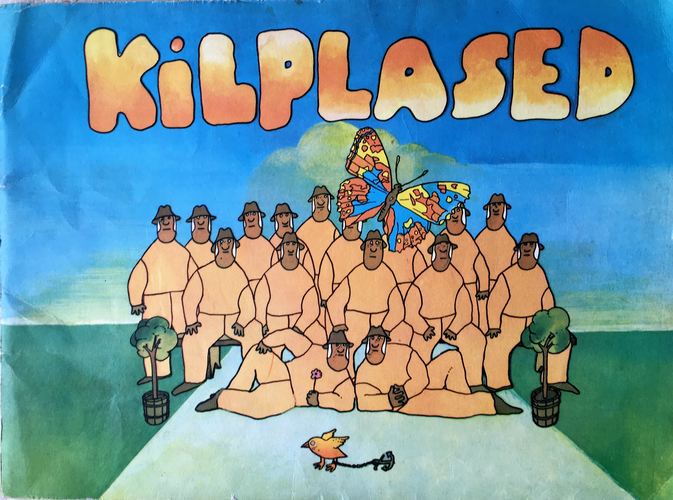

PP: My first cartoon book was published in 1977 more than 50 years ago.

Kilplased with Kaarel Kurismaa (Kaarel did the colors, book published by Kunst, 1977)

Z: What were your influences?

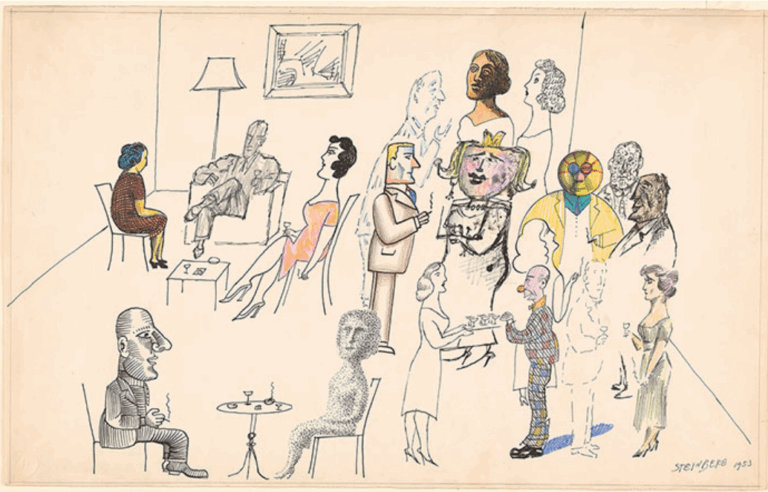

PP: My influences in caricature come mainly from the Czech Republic and Poland. They had very different styles. It was possible to subscribe to or even buy their humour magazines at certain kiosks. It was like a window to the world. I created my own drawing style. I even have lectures for my students because I have this material to show them: how I started and how my drawing has developed after three, five or twenty years. I have a lot of drawings connected to images, playing with lines and images. It’s not political satire or newspaper caricature. I always tried to be against the system but my main interest was to play with visual images. Saul Steinberg was very important to me. It was good preparation for animation. You have to break the world into pieces and reassemble them in a new version.

Techniques at a Party 1, Saul Steinberg, 1953

Z: In your country was there more liberty for cartoons in a newspaper than for films?

PP: Films were, of course, subject to stricter control because they were broadcast on television and shown in cinemas all over the Soviet Union. Officially, animation was an art form for children, so it was easy to say that children wouldn’t understand.

For drawings published in newspapers, it depended on the type of newspaper that published them. They could decide that it was politically incorrect and that it was a political mistake and then punish the person who had decided to print it. When I started in the 70s, they would sometimes find that certain drawings were against the regime, so they would phone the publishers of the newspaper or magazine and order them to stop publishing Mr Pärn. It wasn’t official, so you could bring in your drawings and they would accept them, but they were never published.

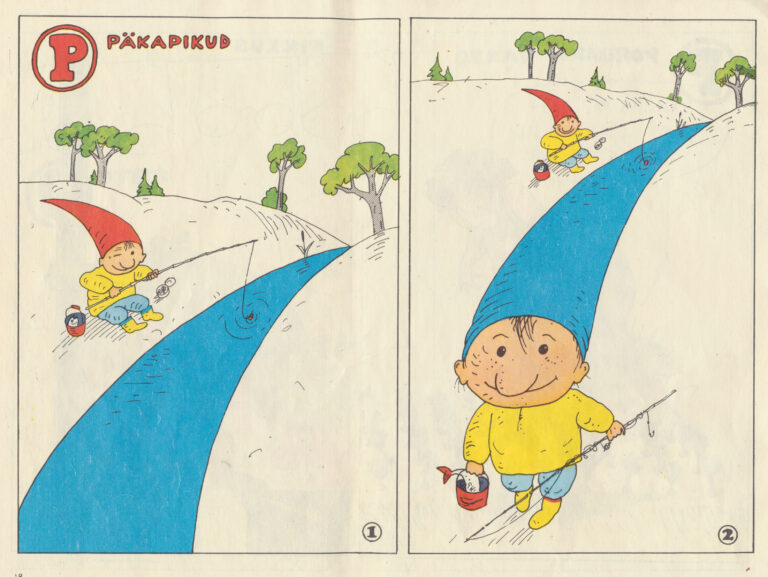

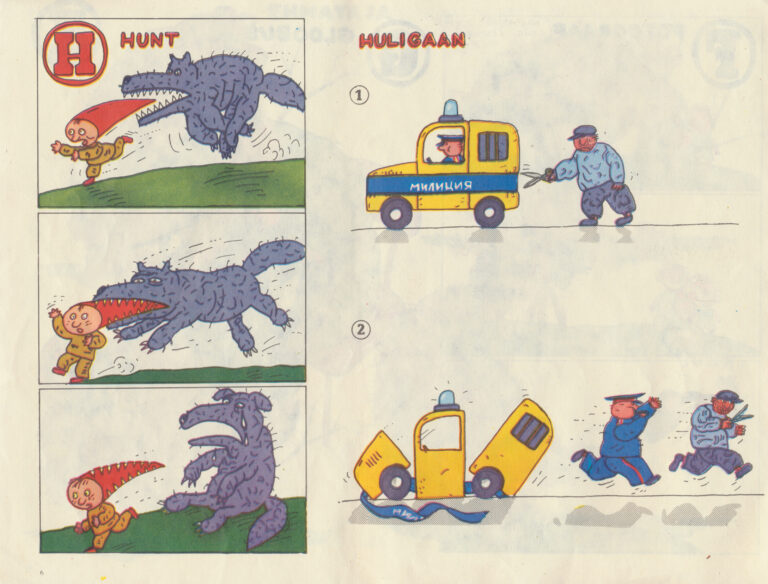

Naljapidi aabits (The Funny Alphabet) comic book, drawn by Priit Pärn and printed in 1983

In 1987, they tried to extract borate in Estonia, which would have destroyed nature. There was a protest movement. My drawing on phosphate fertilisers was published, depicting a man on a cart pulled by a very skinny horse, throwing this shit in the field and saying ‘And shit…’. and the piece of shit falling on the ground is the Estonian map.

The Central committee of the Estonian communist party punished the chief editor of the newspaper. People made t-shirts and hats with this drawing.

OP: Even today, it is the best known caricature drawing in Estonia.

GS: One can describe your universe as an absurd surrealism. Is there any tradition in Estonia? And what is Olga’s background?

OP: I was born in 1976, just the year that Priit started doing animation. I come from a family of architects. My family broke up. My mom started to do animation films so I grew up in an animation family. I saw how life of an animator was hard. She started making films with sand. I saw her working day and night under a large rostrum camera in a darkroom. When I was a teenager, I used to say two things to myself: never animate, never teach. So, after the Art Liceum I finished Belorussian Academy of Arts with a specialisation in etching, was fascinated by gravures and for making money I started to work in Animation as an Artistic director, storyboard artist and sand animation animator. I was teached by my mum all secrets of her experience with the sand. At the age 26 I understood, that I want to starts my own carriere as an animation film director and I choose as a post graduation school La Poudriere in France (Valence). In the video library of the school I had a chance to watch Priit’s films and my favourite one was 1895. When Priit came to Valance to teach my group in 2005, my school alow me to ask Priit to be my mentor for my diploma film The Dreamer, which I made in so called black painting style. After La Poudriere I was working half a year in Paris as a storyboard artist (for the series Zoe Kezako) and then Priit invited me to Estonia to live with him. I went. From that moment we’ve been unseparated and we are working together. In 2014 we’ve completed the film in sand animation technique, which we upgraded heavily (You could see these innovative process in my Making of Pilots on the way home). Probably, important moment is, that I love to do illustrations. Some of the books we do together, but mostly we illustrate separatly. I have illustrated 11 childrens books and working for the Estonian Children Magazine Täheke quite often.

Making of Pilots on the way home by Olga Pärn

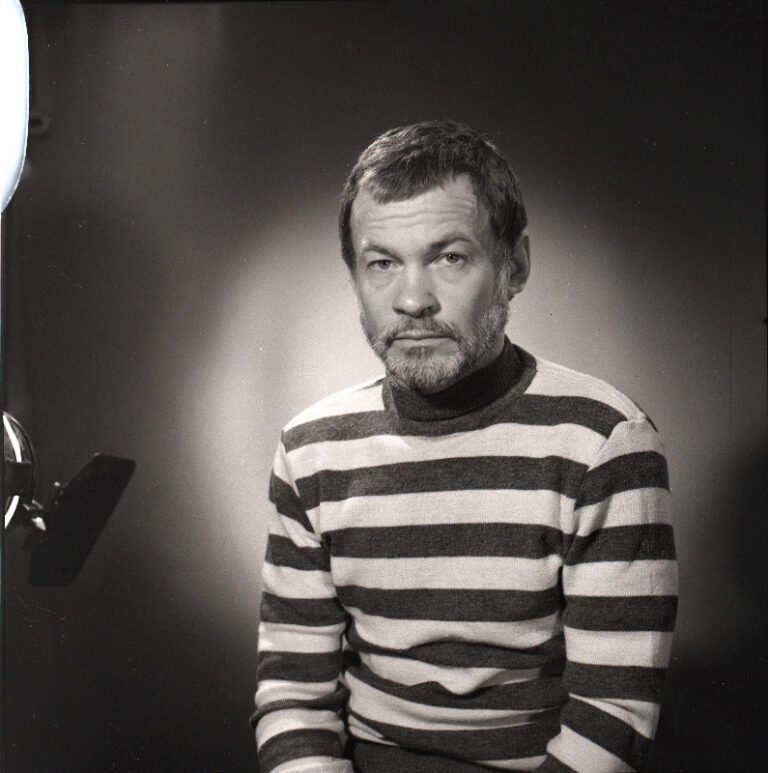

Priit and Olga Pärn (photo: Märt Rudolf Pärn)

PP: Things were a little different in the other Soviet republics than in Estonia. When I arrived in Estonian animation in 1976, there were already animators who had come from cartooning, so animation was very popular in Estonia.

The studio was founded in 1956 by two people who made one or two films a year, mainly for children. When I arrived, there was a certain stagnation, it had become old-fashioned. Then a great team of young animators arrived and started making films. The atmosphere was very different from that in Moscow or Belarus.

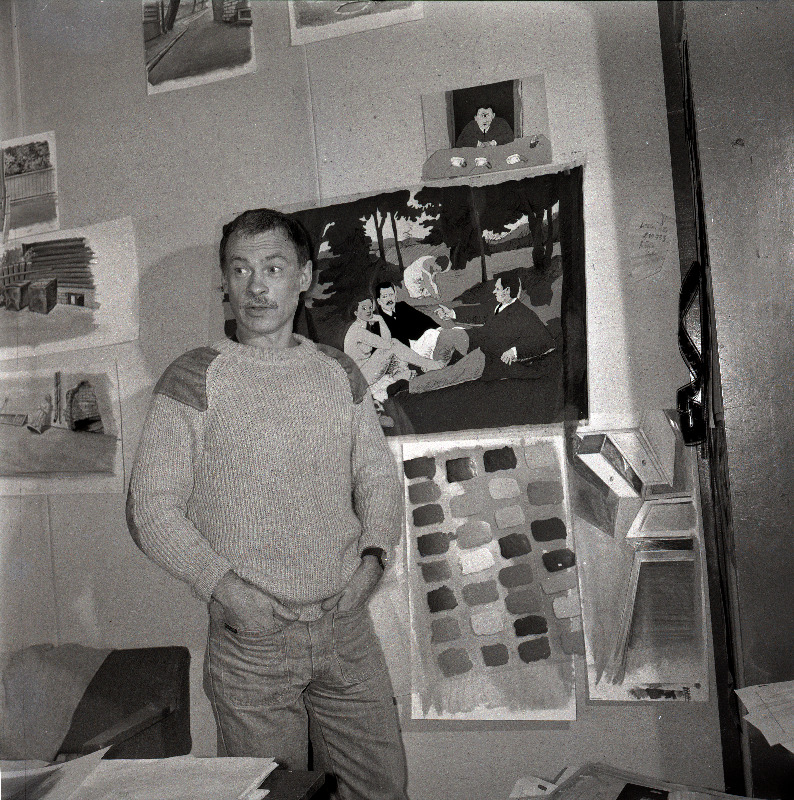

Priit Pärn (Estonian Film Institute)

OP: What is very important to say is that Estonia became part of the Soviet Union later. At the end of the first World War, Estonians gained their independence. They were independent until the second world war. The Estonian language belongs to the Finno-Ugric group of Languages. When I arrived in Estonia to join Priit, I immediately started learning Estonian, because all this richness, playfulness and out-of-the-box thinking is linked to their language and way of thinking. I came from Belarus and when I arrived in France, all the words related to cinema came from French. I immediately started to learn and speak this Latin language. But when you arrive in Estonia, you feel like an idiot because you don’t understand any of the words.

PP: Not completely. Estonia has these international words like sport, electricity, tractor… But the Hungarians and Finns have invented their own words to describe these concepts. Recently, these English words were incorporated into their language.

GS: Is there any tradition of absurd surrealism in literature?

PP: Maybe it’s more theoretical. It’s difficult to make a surrealist animated film. Surrealism is totally serious, not comical. The group of surrealists expelled Mr Dali because they thought what he was doing was funny or ironic.

On the other hand, the absurd dimension is present.

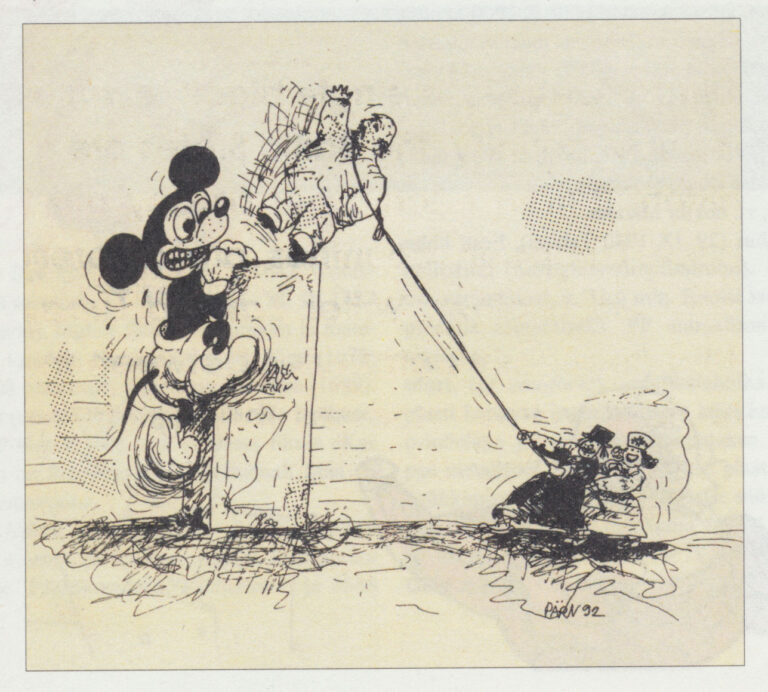

Priit Pärn’s caricature from 1992

OP: I think that the resistance of Estonians and the resistance in animated films is connected. Priit’s resistance lay in the fact that he thought outside the box, whereas everyone else was forced to think inside the box. Film artists from the soviet union, in particular, have all censorship inside of your head, so called selfcensorship. You don’t even realise it because that’s the way your mind works before you realise it’s censorship.

When the Soviets came to Estonia and killed and deported many people to Siberia, Estonians still remembered the free times. Some artists had learned art in Paris. The Soviets weren’t able to destroy all the culture. There was still freedom in the minds of Estonians.

PP: I can’t explain why, but the Estonians were a bit more allowed to do certain things. This play with caricatures has always been on the edge of what was tolerated.

In general, I already know exactly when I make a drawing whether it’s going to be published or not. It was an interesting game. For us, the corridor was not as narrow as in Moscow. We could go in a gray area. Olga saw this in such beautiful colors.

OP: Of course.

Naljapidi aabits (The Funny Alphabet) comic book, drawn by Priit Pärn and printed in 1983

Z: During a dictatorship – and I think it was the same in Portugal – you create a certain type of metaphor to resist and you almost invent your own language, which is much more powerful than when there is a revolution, when everything changes and everything is possible.

PP: They can find something critical and they don’t know how to publish.

Of course, you can see that they’re afraid of what to do next. It was a game.

OP: Priit drew a lot of caricatures based on the interplay of words and lines in an abstract way. It’s very enjoyable for an open mind.

PP: It’s close to animation.

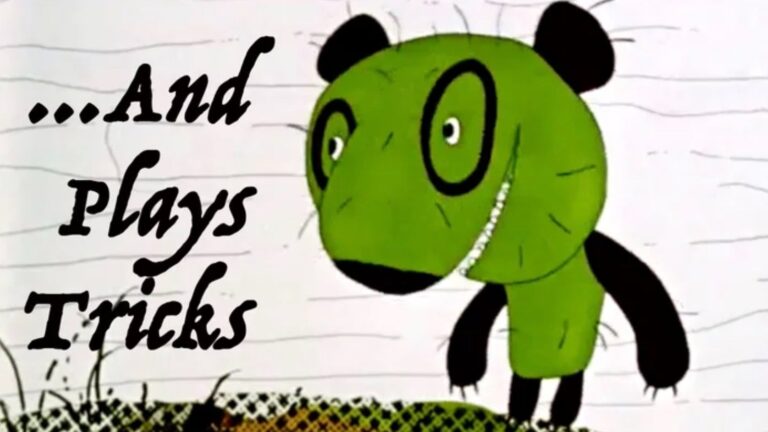

GS: In some of the first films, for example Time out [Aeg maha, 1984] or …And play tricks […Ja teeb trikke, 1978], the organization is made with an association of forms that resemble each other, one inviting the other, sometimes like visual puns, calambour visuel. What is the method to link your scenes and create a coherent unit? You have a lot of caricatures but you have to join them to make the film.

Time out (Aeg maha, 1984)

…And play tricks (…Ja teeb trikke, 1978)

PP: Caricature is a very short animated film, in one frame. One picture is telling a story. If I can’t tell this story with one frame, I can tell it in a strip of three frames. If I can tell it with more frames, I have more freedom. The year after Breakfast on the grass won the Grand Prix at the Tampere Festival in 1988, I was on the jury and a professor from a film academy told me that he wanted to invite me to teach their students for one semester. There were not animation students but live-action filmmakers. I had never studied cinema, how could I teach it? He told me that all I had to do was throw a stone in the water and I started to design this stone. I started in January 1990. I tried to understand what’s happening in my head when I create a caricature. I ended up working out a system. You need an absolutely free imagination and, at the same time, a very structured way of thinking, like mathematics. You create something, then you analyze it. It was finally a very organized system.

In the early 80s, the soviet Union was in a very difficult economic situation and culture was always the first to be threatened. After Triangle, I couldn’t make films and then I found a magazine for kids to publish caricatures for 10 years. I’ve collected these drawings in a book.

Naljapidi aabits (The Funny Alphabet) comic book, drawn by Priit Pärn and printed in 1983

At the Tallinnfilm Studio, 1982 happened that no one was ready to start a new film and they asked me to do it, even though I had decided not to make any more films. But I decided to help them and I made Time out.

Time out (Aeg maha, 1984)

OP: This film is connected with the drawing book made just before.

GS: One gag follows another. What creates the link?

PP: It was more complicated because the pictures were not much connected to each other. The idea came from this drawing with a cat running around, like when you’re in a hurry in the morning. You try different things, then the clock is broken, and this person is free, and the world where this person finally arrives was very dangerous and military with soldiers.

When the film was almost finished, the studio recognised the military references and told us we had to cut certain scenes. The colourist and I negotiated. We decided to cut certain scenes. If we hadn’t done that, they would have trashed the whole film anyway. It’s a funny story because the film was supposed to be 10 minutes long and after cutting a lot scenes it was still 10 minutes long. Originally each action followed on from the previous one. When we cut certain actions, we had to combine the remaining actions.

OP: There is also an uncut copy on videocassette from Canada.

PP: It is not an uncut copy, it is copy before the final cut. There are still soldiers. Then we had to cut them. It was impossible to cut all these scenes because the soldiers were everywhere and I suddenly had the idea of making them into clowns. They agreed. In those days, we used transparent celluloid sheets with the drawing on one side and the paint on the other. The poses of the soldiers and the clowns were exactly the same.

OP: So they repaint the soldiers to clowns.

Time out (Aeg maha, 1984)

GS: During that first period, you were stringing together one visual gag after another. But in general you use parallel editing, in Luna Rossa for example, where we follow different actions in different places, thanks to the observer behind the screens. In Breakfast on the grass also.

PP: In Breakfast on the Grass, there are four parallel stories and I realised at a certain point that it was perhaps becoming too complicated to understand. The four stories don’t start at the same point, but they all end up in the garden at the same time. I designed the structure so that the story ends when each character has made their contribution to Manet’s painting.

There are two possibilities: the first is that they don’t have the missing element, they try to find it, or they have it and lose it and find it again. To obtain this element, the character must do something related to humiliation. I had to build this schematic construction. I had maybe five different ideas and then I selected the best idea that fit the story. For me, making a script means making a construction. This is what I teach to my students. Every film is a line you can draw starting from zero, lasting 10 minutes or two hours. I have to calculate what I can do. For beginners like students, I give some rules, some tricks or techniques and they will create step by step.

Priit Pärn (Estonian Film Institute)

GS: When you gave a talk in the Lucerne International Animation Academy (LIAA) in winter 2009, you gave the example of the hammer and the nail: who is stronger? the hammer or the nail? And if, instead of a nail, it was a screw: who is more strong? And why? Can you develop this idea again?

PP: The question was not who is stronger. It was an analysis of system . In my exampel the system cosist from three elements : hammer, nail and screw. You had to describe elements of tis system and also connections between them. And you giving to this objects some human feelings. A hammer is just a tool for a nail. A nail needs a hammer, but if a hammer is used on two pieces joined by a nail for 200 years, there is no longer any need for a hammer. A couple is united by a relationship of love and hate. If you add a screw, it becomes a triangle. What might a nail feel towards a screw: love? I think the screw is more sophisticated. The nail wants to stay with its hammer and doesn’t really want to see that damn screw. But a hammer can be used to screw in a very brutal manner. Then we will create the story. How do we put that online? What do we show first? The hammer, then the screw, or both together. There is moisture. The nail hates the hammer. Or the opposite: at first, they seem to form a lovely couple, then the screw arrives. If you replace the hammer or the screw with a human being, you already have a story for perhaps a feature film or a novel. So it’s a possibility to analyse or a structured jealousy, using A, B and C. I won’t go into too much detail about this technique, but if you’re working on building this abstract structure, try to build it as long as possible without assigning names. No A, no B, no hammer, no name. If you immediately give names like, for example, a dog is running on a road and a car hits a tree better to avoid the dog. If it’s possible, try to work on the result without reason: a car hits a tree, why? You’re going to develop ten different possibilities and then look at what suits you best. If you immediately decide that it was because of the dog that the car hit the three, it’s fixed in your brain and it’s very difficult to change, especially for beginners.

GS: How do you organize the ideas that come? You accumulate notes? The ideas are coming spontaneously? In all the films there are a quantity of ideas, some being developed, some not. How is it developed? How does one idea bring another?

Z: Plan by plan or situation by situation, is there an invisible layer you want to convey, beyond what is just visible? Do you preserve it without knowing exactly what it is, or do you have a clear idea of what you want to achieve, from story to screen? Luis Buñuel once said, “If you ask me what it is, I cannot tell you exactly. I feel it more than I understand it. Anyway, if I could fully understand it, it wouldn’t have the same result.” So, maybe there is an invisible film that is not told, something that appears beyond its surface.

PP: I actually try to follow a basic idea. Salvador Dali likes to say that all his images are coming from night dreams. I don’t really believe him but I have one film that came from my night dream. I didn’t remember it exactly when I woke up. Somebody told me a story or maybe I was in the cinema watching a film or somebody showed me a script. It was that Karl Marx goes to the hairdresser and shaves all his beard and hair. Nobody recognizes him because we all have just seen one portrait of Karl Marx. It seemed funny and I told the idea to my friend and then step by step I started to feel that maybe it would be interesting.

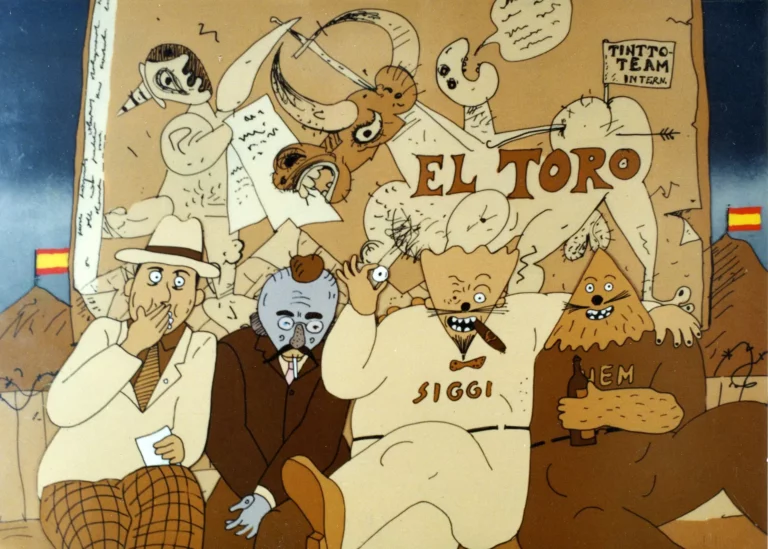

Karl And Marilyn (Karl ja Marilyn, 2008)

During the period when you’re making the construction in your head, or you will write a simple version, for example, Life without Gabriella Ferri, the longest of our films, the second we made together. There were parallel stories because all the time, something would appear, then come out and be linked to the story. It’s a construction: a stork is flying, is shoot and starts to fall down. I needed to kill this runner. How to get rid of this runner? He runs and says ‘life is nice, life is nice’ and then the stork falls down and goes through his chest.

Life without Gabriella Ferri (Elu Ilma Gabriella Ferrita, 2008)

Life without Gabriella Ferri (Elu Ilma Gabriella Ferrita, 2008)

OP: It’s a destiny, Priit!

PP: Yes.

Actually when I write and start to draw a storyboard on small pieces of paper in the beginning. I put the papers on the floor and move them like cars. I’m already editing it, but I can change it a lot. Some people spend a lot of energy and time drawing up a storyboard in a very definitive way. This is sometimes necessary if you want to apply for money. But in the same way, the script settles in your head and is already finished. Unconsciously, you don’t want to change it. If you play with these small pieces of paper – you will come to the storyboard – it’s a long way.

When I work alone or when I work with Olga, the films are visually quite different. Every film has a different story and every film deserves its own visual work. It may be the most difficult but the most exciting period in the making of a film.

OP: The films we made together with Priit are constructed stories. It’s one type of film. 1895, made by Priit is another type of film. It is constructed like a huge calembour (french word for pun).

1895, Priit Pärn and Janno Põldmaa (1995)

PP: They are epical films not like Hollywood style scripts. What happens in a film results from the previous event and provokes what follows. For 1895, I gave myself some rules. It was a long story made to celebrate 100 years since the invention of cinema and suppose to be shot in Talinn’s puppet film studio by our old puppet film director (by Elbert Tuganov). It was to be partly financed by Germany, which wanted to make a film showing a praxinoscope and other pre-cinematiqe objects. They had a problem with the script and they asked me to help. I did something and then it came out that there was no money from Germany. It then transformed to a Finnish company prepared to invest in the film, but wanted a film in drawing and for me to direct it, which I had no intention to do. All eastern european studios had already collapsed at that time. I was supposed to jump out from this train to let the project to Janno Põldma, the cameraman. But then I started writing and suddenly realised that it was a fantastic way of making a really good film. I wasn’t interested in making a film about the invention of cinema. At that time, terms such as ‘politically correct’ had already appeared. We are in the most comfortable position to make a film, but this politically incorrect film will insult everyone and every nation. The film should therefore be a total lie. For me it is an epic film. The main hero is Jean-Paul, which nobody knows in the beginning.

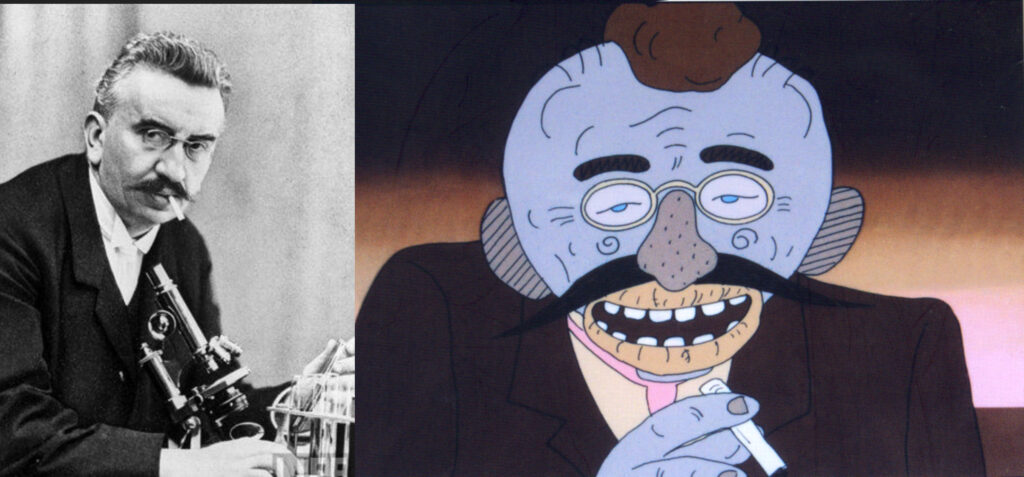

The design of the main character (on the right) made by Priit Pärn for animation film1895, the photo of Louis Lumiere, the prototype of Jean Paul in 1895 (on the left). From archive of Olga & Priit.

OP: Did you want to be sure that everything was credible?

PP: Yes. I worked out the character design of Jean-Paul. I used a portrait of Louis Lumière with this cigarette in his mouth. Jean-Paul smokes a cigarette throughout the film. All the dates are indicated so that this piece of film dates from 1852. If you try to follow the dates, you will notice that they are incorrect and not chronological. We’ve used a lot of references from the history of cinema, but we’ve just taken them, we don’t control them and we don’t control whether they’re right. We had to create silly little sequences. In 1995, I was almost 50 and I was quite good at it. It was the first film in which I used a voice-over and it was quite exciting, but it wasn’t easy either, because I realised that I was describing what you could see to create the text, so the text and images give something new. If you look at student films, they’re always 97% written text which is mainly a description of what you can see, like a radioplay.

The film was made after Hotel E, after which I stopped making films anymore. Then a woman from Channel 4 offered to fund a new project if I started a new one. I said ‘thanks, but I don’t make films any more’. Then this film with Jean-Paul came along and I sent the script to this lady. She replied that it might be humour, but not humour for British audiences.

We finally made the film with Finnish money.

1895 by Priit Pärn and Janno Põldmaa (1995)

OP: They liked Hotel E, didn’t they?

PP: Yes because Hotel E is simple, with a binary structure. If Breakfast on the Grass was for me a farewell to the Soviet Union, Hotel E was on the border between the Eastern and Western systems. It’s not a film about me. The idea came to me after an exhibition in the late 80s. I travelled to take part in festivals and juries in France, Belgium and elsewhere. It gave me a wonderful feeling and coming home was so depressing. Every time I received an invitation, I went. The changes in Estonia were very quick. In those days, there were no mobile phones. You had to come and sit someone down to ask them to explain what happend during your absence. You understand how you have to behave. This idea of two different rooms in the film, with someone going back and forth, was a good structure. There was this strange black and white world where you’ve being punished. That part eventually evolved into stagnation. They’re just sitting there for that reason. And there was this colourful, beautiful world where one person was missing and repeat the same thing, but technically at a higher level, with a beautiful table.

A lot of people asked me who I was to criticise?

Hotel E (1992)

Channel 4 were probably expecting something similar, which could be very tangible indeed. Hotel E may be in some ways critical, but criticism isn’t the main aim. The main thing was to build on this visual base. A lot of work went into creating these two different worlds, thanks to a painter, Miljard Kilk, who did an incredible job.

Making 1895 after this gave a very good feeling of total freedom.

Miljard Kilk with his painting Europe (Esti Joonisfilm – photo: Olga Pärn)

OP: Where did the idea of using actors in Hotel E come from?

PP: The idea came suddenly.

OP: It was the first time that you worked with actors. (p.s. in fact not the first time. Priit used Mati Kütt as George for the opening sequence with the same name in Breakfast on the grass. Mati was photographed for the key frames, which was used as a references for the painted animation sequence.)

PP: As we had to create two completely different systems, one in dirty black and white world with flies, the other so called beautiful world, we came up with the idea that the colours of the second system should be so soft that you’d feel bad looking at it. It’s beautiful but it’s too much! Millard spent a few months balancing his colours and came up with the idea of limiting the colour palette, only 11 different colours and it seems that all the colours match each other. The characters in the colourful world are beautifully painted, but their movements are a little clumsy. If you’re drawing characters whose anatomy isn’t quite perfect, the movements need to be very stylised. But if the characters are anatomically correct, they should move correctly. Like in Breakfast on the grass.

OP: Yes, that was not the first time.

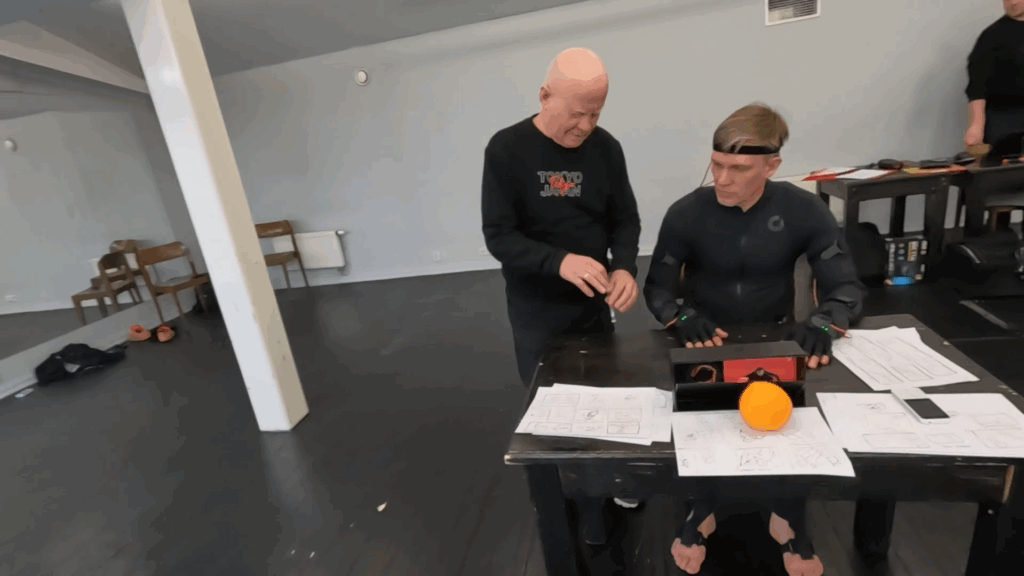

PP: To show that the characters really enjoy their life, all the movements were slow. They enjoy how they are moving. And it wasn’t easy to obtain these movements. Now for Luna rossa, we have actors with motion capture suits which allow a fine control of the body. But at that time, to preserve a form of stylisation with rotoscoping, we filmed the actors and played this video image on a very old black and white television set, then shot the image on 35 mm black and white film. The image was so bad that it was impossible to see the small details. It’s impossible to draw a line from it. The result is this stylisation, with flat colours. The animators selected key images and interpolated between them. So it wasn’t exactly rotoscoping.

Hotel E drawings

Z: What I like most about in Luna Rossa is the part where the woman moves. It’s strange, almost like a collage of elements and movements, in total contradiction with the adaptation of real-life footage. The animation is indeed not treated like rotoscoping but still remains hyper-realistic. It’s a mixture of real footage and ambiguous movements. It’s the opposite of rotoscoping. There are different approaches in this contrast: gravity, sensuality, sometimes a vicious behavior of characters, and at the same time, a very naive representation. It’s just perfect!

PP: Thank you.

Hotel E (1992)

WH: In Luna rossa, there is the same paradox : a movement obtained by motion capture produces stylised movements.

OP: It’s exactly the right bridge between the films. Watching Hotel E, I was really interested to know how Priit could work with actors. It’s rare when an animation director is working with actors. Tanel Saar, who plays the main character, is an actor in physical theater. He staged the Breakfast on the grass in a physical theater.

PP: He did not use the film’s script, but tried to create an animated film on stage in the theatre. It was very fresh and very funny.

Frames from Priit Pärn’s film Breakfast on the grass (1987)

Eine murul, poster for the theater performance composed by Olga Pärn – director of the performance: Tanel Saar (teaser of the play)

In 1987, Priit Pärn’s animated film Eine Grul (Breakfast the grass) was released to the public. This grotesque tale of four human fates aptly portrayed the perestroika mentality of the time. Eine murul (A grasshopper) is still one of Priit Pärna’s best-known works and reminds us why the Soviet Union was bound to collapse sooner or later. Director Tanel Saar reflects: “I’ve always been fascinated by Pärna’s cartoons. First of all, I’m fascinated by how the stories of four people are so skilfully woven together. Secondly, I can also sense something of today in this socially critical story from 30 years ago. “Eine auf Grä is a satire on bureaucracy. It seems to me that, even today, the individual has to face up to many social, societal and, in particular, bureaucratic horrors in the pursuit of his dreams. Through humiliation towards a goal. I am tempted by the challenge of finding a way of translating this fascinating animated film into theatrical action – how to find a counterpart in a live performance, with live music by Madis Muuli. And still understand how far can and must a person go for their dreams?” The premiere took place on 4 May 2017 in the Tornisaal of the National Library of Estonia.

OP: It was in 2017. They invited us to the theater and he talked with Priit about the construction of the play during the process of staging it. He wanted Priit to collaborate. Priit had the idea for the script of Luna rossa. We had these fantastic actors and Priit experience with Hotel E and his ability to work in choreography. And there was motion capture.

Tanel Saar (photo: Laura Raudnagel/ERR)

PP: To be precise, the idea of using motion capture came when we decided to make the film. The story was not finished yet, but it was clear that there would be security cameras, which are always placed high up. You can imagine if somebody approaches such a camera, he’s deformed, his head is big and his feet are small. And you have to move them correctly…

That’s when the idea of motion capture came up. Nobody in Estonia or in Baltics or Scandinavia knows about it except for commercials.

Making of Luna rossa

OP: Nobody used it yet for an artistic animation film.

PP: I really don’t know why suddenly I had the idea of taking different liquids to security control. Two young terrorists each take a sip of a different liquid and kiss in a plane.

OP: First it was just a kiss. It was a joke.

PP: It’s a bit similar to the Karl and Marilyn story: you start from a small skeleton then you put meat around this skeleton.

Andrea Martignoni : So why did you place the story in Naples?

OP: It’s an imaginary Naples, you know.

Luna rossa (2024)

AM: Yes, I know. We also see Toto… and Gabriella Ferri in the stylization of the character and also the photo that came from the drawer.

OP: Yes, you recognized all of them!

PP: It’s the only time Gabriella Ferri and Renzo Arbore are in the same photo.

OP: I was looking for reference photos on the internet for making the character design of Gabriella in 3D, to understand how to construct her face, because Gabriela is not with us anymore, she’s gone. When we were looking for that, we found only one photo where Renzo Arbore and Gabriella Ferri were together. This photo is in the film, in the drawer.

PP: In Conversano Festival Imaginaria, Luca Rafaelli told us that Renzo and Gabriela had some romance, shortly.

OP: Luca was sure we knew. We made the whole film without knowing. We knew they were singing together because Renzo was doing the show on Italian television and when he gave his last concert in Rome, at the end of OrchestraItaliana, the first thing he said was that they would perform the song Luna rossa, sung by great Gabriella Ferri.

Luna rossa (2024)

PP: Finally we’ve already worked on the film and we knew that it had to be the song Luna rossa. I remember I found a version of it. The Moon is already in the sky and from somewhere, maybe from an open window, you can hear Gabriella singing Luna rossa. Then we found this concert version of Luna Rossa with Renzo, Eddy and Francesca singing together in neapolitan dialect.

OP: That was recorded for television. There was no author rights for that because it’s on YouTube.

AM: You also used the Claudio Villa version, didn’t you?

OP: Yes, we found it later. At some point we understood there was no place for Gabriella’s version of the song.

PP: It was so complicated for the rights.

OP: For the version performed by Gabriella. We understood that for the story, we will use three versions. The one with the Orchestra Italiana with Renzo Arbore, Francesca Schiavo and Eddy Napoli, who is the son of the poet Vincenzo De Crescenzo who wrote the lyrics in neapolitan dialect. We were looking for different versions and we found the version, performed just by Eddy along (also in Neapolitan dialect) and then for the Grand Finale we used the Claudio Villa‘s one version, performed in Italian.

AM: One of the most famous versions of the song. There are at least 50 different versions of this song, almost as many as O sole mio.

OP: Yes, it’s one of the most popular, and we found that Claudio Villa’s version is so sad, it was so heartbreaking that it had to be the final song. It expresses all the tragedy of the situation.

AM: This song was obviously the right choice if the film is set in Naples.

OP: That came all together because we’ve never been in Naples and Priit said that probably after this film we shouldn’t. We constructed the film like a fantastic piece. It’s not connected. We used their characters (the artistic, stage credos of them) because they are beautiful. And little by little we realised that the story was so tragic and so ugly at the same time. It works best if you set it in a fantasised sunny Italy, which is the most beautiful place in the world you can find. To make you feel bad.

Luna rossa (2024)

PP: It’s not that we decided because, once again, it was a question of what this world looks like. Because it has to be for this film: all the colours and so on, you recognise them in Luna rossa. How did these characters appear? I think it was when we already worked to draw these characters, especially Gabriella. Her face changes so much in the different photos that it’s hard to tell it’s the same person. When we found these three singers singing together, I said straight away that they would be the heroes of our film.

OP: We had a stop frame of them singing together like the video which is on the screen in the plane. We stopped the picture and Priit said: ‘Look Olga, they look like our terrorists. They’re so bloody beautiful! It’s exactly what we need for the film, for that story!’

Luna rossa (2024)

PP: The process of making a two-minute film with a kiss at the end and an exploding plane was the first idea. Now it’s more than 30 minutes. You can make links with other films and these parallel stories aren’t really parallel stories, they just go with the flow of the story: they meet in the street, Gabriella and the guy go underground, he tries to explain by showing her the photograph of Francesca, then we see Francesca on the balcony with her cactus. Gabriella and Francesca change bags, probably with the liquids, then Eddy and Francesca on the beach try to test the liquids: ‘Does it work? Yes, it works!’ He kills his dog, she gets rid of her cactus and finally they’re at the airport.

It’s a very concrete storyline.

Luna rossa (2024)

OP: At the same time, Priit, there is obvious action, but we also follow the feelings. When Renzo watches Gabriella’s recordings in her flat, we sense that there are feelings between them. It’s not sad.

PP: Gabriella is showing the boarding passes from the Bluffansa to Renzo through the camera with the number of the flight. She probably knows he’s watching her and she plays for Renzo, walking with manners when she knows she’s in camera range.

Luna rossa (2024)

AM: You will be very welcome to Naples because people in Naples are very welcoming people. The only thing I suggest is to take care about the security control in Capodichino airport.

OP: The airport in the film was created using Google Street View, so it’s accurate. At one point, when we started building the sets, we based them on photos of Bergamo, so it’s a collage. We used a lot of old vintage photos of Naples, free of author rights, from more than 100 years ago. We took some details and characters from these pictures and they look like shadows standing in the background and looking at what is going on. It’s very important.

Luna rossa (2024)

PP: The shadows are in the plane so maybe not for the first time.

Priit and Olga Pärn in Raphaël Gianelli-Meriano’s film Portrait of Priit Pärn (2006)