WRITING ANIMATION: NOÉMIE MARSILY

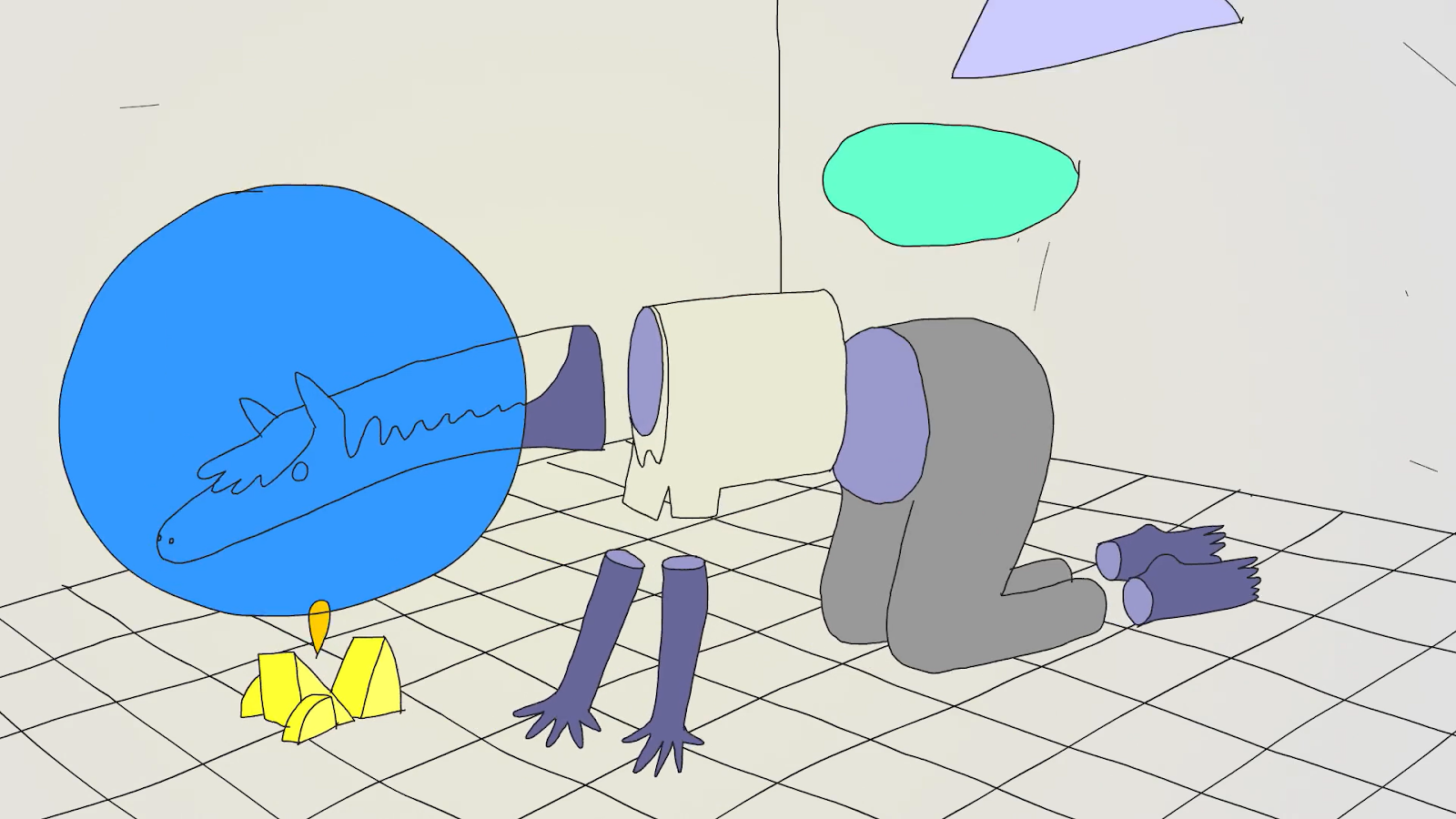

Film: What moves is alive

NOÉMIE MARSILY: Let me quickly introduce myself: I’m Noémie Marsily. I make animated films, including the one we’re talking about today. I also do comics and illustration, so I’m a bit of a jack-of-all-trades. I also teach a bit about comics.

GEORGES SIFIANOS: My name is Georges Sifianos. I was born in Greece and now live in France. I’ve been working in animation for a while now, and I’ve also done a thesis on the aesthetics of animated cinema. I’m interested in both the practice and theory of animation. I taught animation at the Ecole des Arts Décoratifs, ENSAD, where I initiated the animation department. Now I’ve stopped teaching and devote my time to making films. I’ve never done comics.

ZEPE: I’m Portuguese, I studied at La Cambre. Then I worked in several places outside Portugal, including Hungary at one point. When I was quite young, I started doing political cartoons for newspapers, then for comics magazines, but I decided to move to Belgium instead and do a bit of animation because I knew some friends who did.

I set up a website called Beat Bit. William Henne runs it with me. I teach animation and also comics. I like teaching, but I have a bit of spare time where I make short films. At the moment, I’m doing a series and a feature film.

But what interests me most about your film is the research into the possibilities of short films and the crossover between comics and animation.

GS: I remembered your name, Noémie, and I found out what it was: you made the film Autour du lac. I like that film and I think it’s on the Fontevraud DVD…

Autour du lac, 2013.

I’m going to link the dramaturgy with the graphic universe, and we’ll come back to the dramaturgy in a moment. You use a ligne claire (clear line), which seems to be a Belgian characteristic. How do you choose your graphic universe? Do you consider that you have your own “style”, to which you remain faithful and try to develop it? That’s the first possibility. Second possibility: is it a style that you come up with on the spur of the moment? And third possibility: are you trying to find a graphic universe appropriate to the subject?

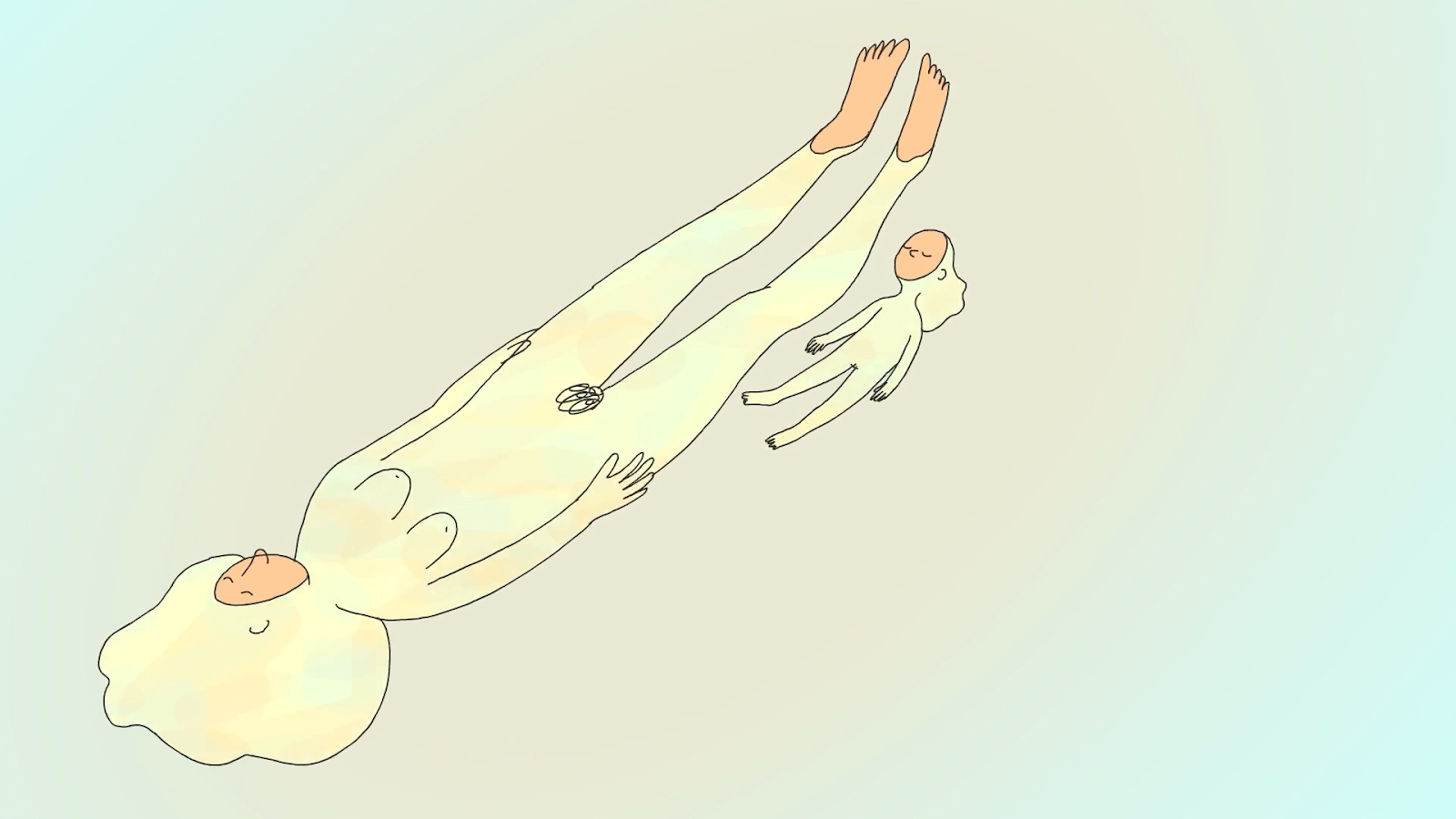

NM: I think it’s a bit of a mix between the second and third proposals. For this film, I didn’t work in clear line right away. At first, I experimented with animated paint and pencil. The painting because there was this dimension of contemplation that is still present in the film. For example, the tree that’s lying on the ground, or the images that stand almost without being animated. I wanted to paint them, but I also wanted to paint the movement. I did two painting tests: the slug that wanders across the tiles and another with clouds in the sky. But it turned out to be very laborious. I need to keep a certain spontaneity. I think I have a lot of patience, but I still need to see that things are moving forward. So I quickly started doing tests in clear line and, in the rhythm of the work, it worked better as a method. It meant I could see the results straight away, and it was easier to go back and correct things. Still, it took me a while to get the hang of it. You speak of an appropriate graphic universe: it’s a fairly fragmented film, and I still wanted to achieve graphic coherence throughout.

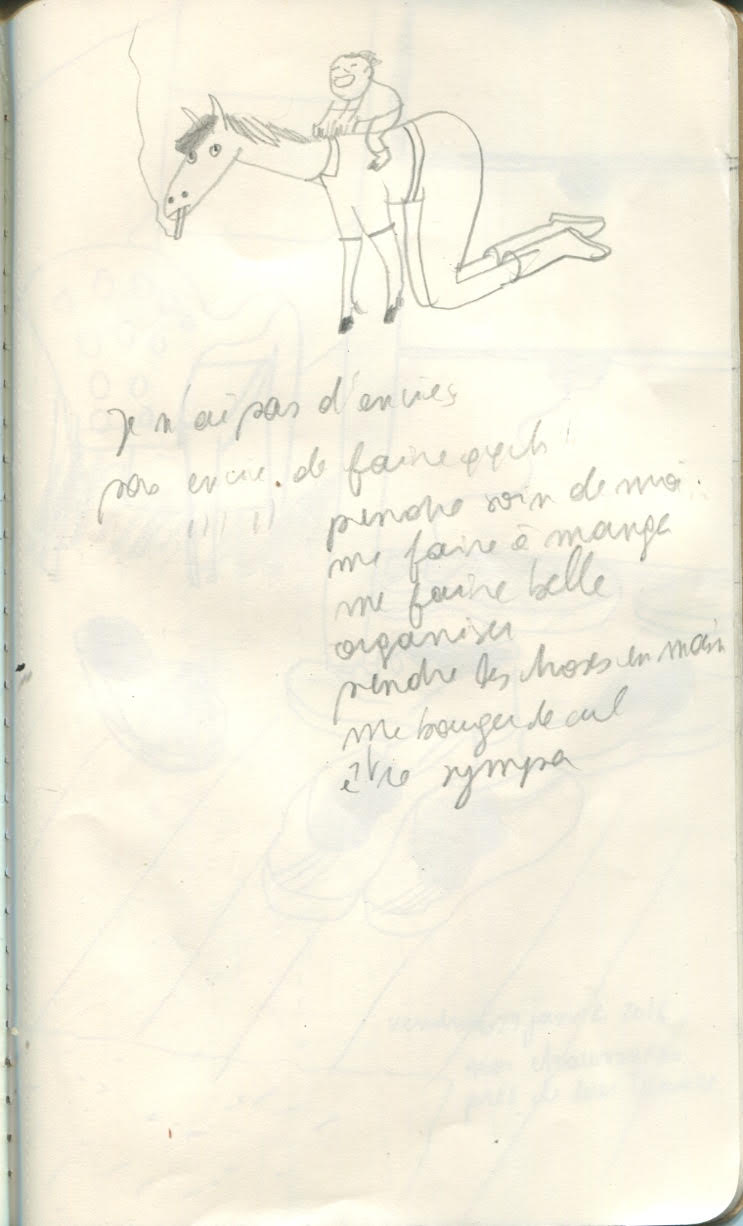

GS: How do you come up with ideas? Were there vague desires that emerged little by little and a story that took shape afterwards?

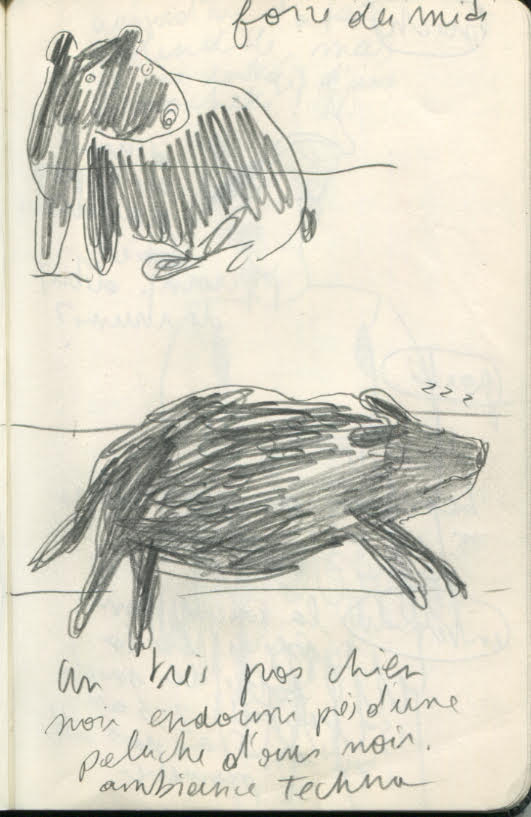

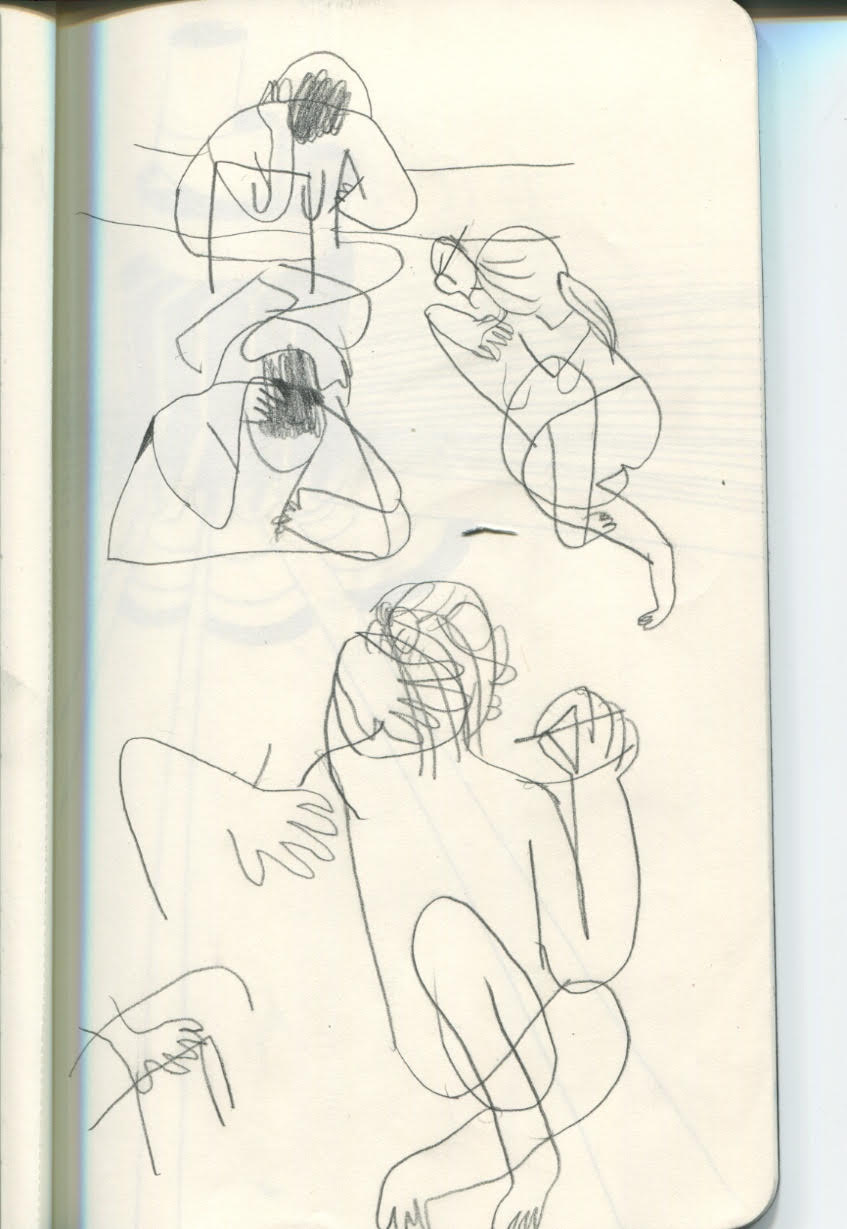

NM: It started from elements that were in my notebooks, where I jot down ideas, write and sketch. I have a lot of them. And when I revisited them, there were several avenues I wanted to develop, but I didn’t really know what the story would be. And at first I wasn’t even sure I wanted to make a film. Maybe I was thinking more along the lines of a book or a comic. It really went off in all directions, so there was this autobiographical dimension right from the start in the fact that I went looking for elements in these notebooks, even elements that were sometimes several years old. I realized that movement was central, so I decided to make a film instead, saying to myself that if I wanted to work on movement, it would be more coherent to do it in animation. So I started animating these little sketches without really knowing where they were going, just out of a desire to see what I could do with these images in animation. At a certain point I said to myself that I was going to make a short film, without really knowing what. I made a kind of animatic with these small fragments already animated, other sketches taken from notebooks, pieces of text. I tried to see if there was a way to tell a story with this. That helped me to refine and tighten it up, so that it didn’t go off in all directions. And that led to themes that dealt with motherhood and slowness, which are ultimately present in the film today. So it started out as something very fragmented, which I still wanted to keep while trying to find a narrative. But I never really settled on a story. I didn’t write a script. Instead, I gradually and more precisely identified what I wanted it to be about, in an impressionistic way, with bits of text and ideas for images. I did a lot of rearranging of shots in the film, deleting some and adding others. I fiddled around a bit right up to the end.

Notebook extract

WILLIAM HENNE: I wanted to have something to say about the final aesthetic choice. Zorobabel, of which I’m a member, produced the film. And I remember that my colleagues, at the start of production, had actually expressed the wish to see technical trials with a chalkier line. Noémie thought for herself and finally opted for this technique, which she masters quite well, namely frame-by-frame drawing in animation software, originally intended for vector animation. Noémie has already made films using this technique, notably for the film Black Soft. So it’s a technique she masters very well. And I hypothesize that, in fact, beyond the fact that it’s a less laborious technique, it’s above all a way of maintaining a fluidity that comes close to something on the order of visual writing. In the end, this ties in with the original idea of telling one’s story in the style of a personal diary.

NM: Yes, it enabled me to retain a form of immediacy and ultimately assume this clear-line aesthetic. I hate doing effects just for the sake of doing effects. And here, in the end, I didn’t think it was worth it.

WH: Indeed, my colleagues’ request was perhaps more a matter of coquetry, linked to an aesthetic taste of their own.

Notebook extract

NM: It’s true that I asked myself a lot of questions about this because, in other films, I’ve used pencil a lot. I like it when it’s painterly. But then I prefer that, if j anime to crayon, animation is induced by the crayon tool. I didn’t want to animate the computer and then give a false aspect of crayon. It doesn’t really interest me, even though I love painterly rendering. And I do comics in colored pencil. It really depends on the project and its intentions.

GS: I really like the result and what I’m about to say isn’t a criticism… I have a good memory of Around the Lake, where your pencil strokes had more substance. And so I wondered about your choice. I said to myself: “Let’s take two simple lines. One vertical line drawn with Rotring and another identical vertical line drawn with grease pencil, and let’s examine the strokes. (Which also brings us closer to the Beat Bit website’s experiments with material and appearance). If we were to describe one of the lines as more “rational” and the other as more “carnal”, would it be the clear line drawn with the Rotring that would be described as “carnal”, or the line drawn with grease pencil?

NM: I’m not sure if it’s the aspect that makes one more carnal or more rational than the other, but it’s the moment of the gesture that’s different really. And then, when it comes alive, movement comes into play. It’s not just the appearance of the line. In this case, I worked with a graphic tablet – and I experimented with pencil, and it didn’t produce the same thing – which enabled me to create a kind of floating spontaneity, leading at the same time to a movement that I can’t reproduce with pencil. This is induced by the graphic tablet. Afterwards, I didn’t want to pretend it was pencil, since it was the graphic tablet that enabled me to move the images in this way. I felt it was the right thing to do for this project.

GS: In general, there’s this fluidity of gesture and movement, so I understand this choice. But for me, the clear line gives a more rational, purified feel, which keeps us a little at a distance. Whereas the messiness of pencil and paint has more to do with matter. And since one of my subjects is the body, I wondered why I’d made this choice. But I think I’ve got the answer: there’s both the idea and the desire, and there’s also the possibility offered by the palette to achieve a fluidity of movement. Which is both desirable and relevant in this case.

NM: It’s interesting what you say about setting a distance. I hadn’t thought about it before. But as I started from a very intimate material and I don’t completely assume it, I was perhaps a little inclined to say that, as the animation process is very slow and I’m going to work on this material as if it were fiction, it finally helped me to make a film out of it. It helped me put things at a distance. Maybe I needed to put some distance between myself and the audience by choosing a more neutral or colder rendering. Okay, I’m talking about myself, but it’s not really me. And you can distance yourself from the subject, because it’s all about me anyway, but I’m doing something else with it.

GS: I don’t think that’s the point, but I’d like to see if the producers were right to push for something other than the clear line. For me, the balance between dramaturgy and aesthetic choice is a constant concern.

WH: I have a rather enlightening anecdote about the writing process. I know the ins and outs of production, as I was in charge of production. When we submitted the file to the Film Selection Commission at the Centre du Cinéma, we took a gamble and told them that we weren’t going to give them all the elements of the script, nor provide a detailed animatic, because we wanted to give the director the opportunity to develop things during the animation process and to leave the possibility of bringing in new ideas, new images and new metaphors during the animation of the film itself. It was a bit of a risk, because obviously, in the Commission, they’re going to have to choose four submissions from twenty or so short films. So they tend to stick to something well formalized that lets them know what they’re getting into. There was also the fact that Noémie already had a substantial filmography and that we could also “start” to trust her. In the end, when the project was debated by the Commission, the approach was well defended by an animated film director who was a member of the Commission. Because it’s important to remember that, in this Commission, we mix animated films and live-action short films. They remained open to this more random type of proposal, and the project was accepted.

GS: They’re far-sighted in any case, it doesn’t happen all the time. I do understand this approach, which consists of working in small fragments from scattered notes. Along the way, certain themes can be integrated, others discarded… But how does someone choose to integrate elements that, each taken separately, can lead the film towards one theme or another? Do you show your project to other people as you go along, or do you protect it from the gaze of others?

NM: I regularly showed it to one person. Right up to the end, I was afraid I wouldn’t be able to bring all these elements together. The sound work really helped to hold things together and structure the elements.

GS: When did sound design come into play?

NM: Quite quickly. I was in contact with the sound designer. He was aware of the project and the way I was working, and I regularly explained to him where I was at. We met up a few times for a chat without really working on the sound yet. He needed to talk to me to understand where I wanted to go. It wasn’t obvious to him, even if the project touched him, but I think he didn’t see exactly what it was all about. At one point I had more and more animated shots and I had fragments of text. We decided we had to attack this sound. So we recorded the text fragments without any real structure between them. And it didn’t work. He tried to put them in a bit of a jumble, left and right, but it all sounded far too fragmented. There was no coherence between all the elements. So I thought I had to do things differently. I wrote a kind of poem from the scraps of text. I reformulated it in a much more structured way. It really followed a narrative and, since I already had a lot of plans, I knew better and better how I was going to arrange them, even if it wasn’t quite definitive yet. It gradually became clearer. We recorded the text, edited it and that helped me to move certain shots around. Then Christophe Rault, who did the sound, took a few liberties with the text, so things changed a bit. He made some suggestions I hadn’t expected. He placed certain parts of the text that I was thinking of putting elsewhere. It was surprising for me when he sent it to me. It gave the film another angle. It’s a bit like weaving together shots, images and sound. After a while, it made sense, it was much more coherent.

GS: I think it’s a very good example of collaboration indeed, this “ping-pong” aspect. As far as I’m concerned, I’ve always thought that, when a collaboration works, it’s not an addition of ideas, but a multiplication. In other words, a crossover leads to new twists and turns, not just an accumulation.

A more down-to-earth question: do you use an evolutionary animatic? Is the articulation work done on paper, or is it done by an animatic, with a pre-editing of the storyboard images, and with the sounds, and little by little evolved?

NM: Yes, there’s no paper version of the storyboard.

GS: I’m thinking of all the institutions that demand a standard academic format, but it’s clear that this is not a universal practice. It doesn’t work like that. Sometimes you have to cheat to present them with a project in storyboard form.

NM: It depends on the project. Some need to be storyboarded, but that wasn’t really the case here. It really depends on the project and the intention.

GS: Watching the film, there are certain transitions that I really like. For example, the diluted face corresponds to a plastic vocabulary that I like. It’s a fluid, mobile material made up of moving lines, with snatches of text that can interchange. It’s a plastic material that moves…

Watching the film, I spotted at least two themes: motherhood, with the relationship to the other, who is the child. (Incidentally, I find this more a feminine reflection than a masculine one. Well, that’s an aside. There’s the subjective view of this situation).

On the other hand, there’s the slug that leaves traces, which seems to me to be the subject of recklessness. I see the slug as a third being who is reckless, unlike the others who hide. And then there’s the accident: it’s crushed. I didn’t quite grasp the link between the theme of motherhood, its relationship with the other body, and this issue of recklessness with the traces the slug leaves behind.

NM: There’s the theme of motherhood. You metamorphose into a mother and so, for me, the slug is a bit like what no longer has room to exist when you undergo this metamorphosis into a mother. It’s so time-consuming, so energy-consuming and so disturbing that it’s as if we’re leaving something that continues to exist, like a mollusk that doesn’t have the time, the space or the energy to go on existing. But the slug moves on anyway. It doesn’t give off anything very powerful or fiery, but it keeps on going in spite of everything. Now, I don’t want to get all psychoanalytical on you either, but the idea is to be able to acknowledge the existence of that part of your personality or identity, and to take care of it, i.e. you can end up crushing that part without paying any attention to it.

GS: Is this a call to prudence because there’s responsibility involved? We’re responsible for someone who can’t survive on his own. He had the recklessness of youth, and now we need to give way to more prudence. The slug was a metaphor, representing an alter ego. Was the subject of recklessness intentional, to show this risk? Is this a split being, or a kind of fusion? We’re re-examining a way of being… It’s an opening to life… In your story, it evokes the question of what others think. Like in the pool with the stingrays, where humans stroke them mechanically. I don’t know whether to side with the stingrays or with the humans, or both?

NM: I hadn’t thought about this notion of caution. I thought it was more about a kind of exhaustion. I believe that this character, in what she’s going through, reaches a form of exhaustion as much in her new role as a mother as in her relationship to the world and to others. This character needs to recharge her batteries, away from it all, while continuing to observe the world. The character is more like the stingray who stays in touch, but a little in the background. He can’t completely escape the world either, because the world is interesting. All those shots where we see the city and nature, it’s this character who carries on despite this kind of exhaustion that pushes him to stand back and continue observing life and the world. The zest for life is still there.

GS: For example, I didn’t quite grasp what the biker’s face represented, since it represents the other and takes on a certain importance. In my opinion, it’s not compulsory to have a clear answer. I don’t mean this as a criticism, just as a question.

At one point, there’s also a little bird flying with a slice of bread around its neck. Is there a particular reason for these scenes? Are they simply amusing, like the bird scene, or significant, like the biker? How do these scenes fit into the story?

NM: I’m fascinated by these kinds of details that I see in real life, and I just want to share them with the viewer. These details may not be very interesting, but I think they are. Because I think there’s a kind of absurdity in some of these little details, like a biker chewing gum or a pigeon getting its head stuck in a slice of bread. I wanted them to be part of the film, but they don’t have any particular meaning, but I think these scenes resonate with each other. It’s an introspective film, and I want to draw people into this kind of introspection and say, “Well, if you come with me to this place, you’re going to experience something that’s part of a slightly dislocated identity, which nonetheless continues to be conscious of a whole host of slightly bizarre things to which I want to give importance”. For the biker, the text says at one point that we’re just observing our fellow creatures, watching them live and watching their faces move.

The pigeon is a bit uptight, so it may also resonate with what the character is going through. But I didn’t want to insist on their meanings either. I think there are several ways of getting into this film. In the feedback I get on the film, some people are moved or intrigued by certain shots and not others. Some may miss it completely, but will instead latch on to the narrative via another angle of the film. As William also said earlier, I wanted to keep the creative process open until the end, and I also want to keep it open for the viewer, even if I don’t want to just say “work it out for yourself. I think I’m trying to hold things together so that they have an effect on the viewer. That’s why I call it a bit of an impressionist approach. In any case, I’m trying to make sure that all these little elements, in the way I’ve arranged them and in the progression, in the way they’re animated, in the way the sound and the text come into play, that this whole thing provokes something of the order of an emotion, which isn’t necessarily exactly defined, but that it stirs something up. I think that, if you take them all separately, it’s complicated to determine that such and such a shot is a metaphor for such and such a thing, or to say this or that. It’s more like a recipe: when you eat something, you can’t feel the flavors separately.

WH: I find it interesting to let oneself be carried away by unusual images that might seem arbitrary in the course of the film. But if the author has been challenged by an image, to the point of feeling the need to keep it, it’s because it resonates somewhere in her writing. These images, which may seem esoteric, have not necessarily been clearly formalized with a precise meaning. But as soon as we know that they resonated in the author’s head, we can probably still find something in them as viewers. If the viewer doesn’t find any meaning in certain images, and their meaning remains floating, he or she will simply be challenged by the unusual dimension of these images, which strike the imagination.

GS: I’m careful to distinguish between the notions of “resonance” and “meaning”. It’s important precisely insofar as we’re talking about resonances rather than meanings or logical “causes and effects”. We are entering a narrative that is poetic rather than prosaic. Instead of looking for the logic of cause and effect and structuring as in a detective film, we’re dealing with evocative associations of scenes.

Does the narrative rely more on the text to explain, rationalize and convey the significant aspect? And as a result, are the images freer to wander? Or could it be the other way around?

NM: As I was saying earlier, the text helped structure the film, serving as a narrative thread. Without the text, it becomes too hermetic. For a while, the text had a much more obvious form, but as the sound engineer also played with the text, it sort of rewound the tracks so that we didn’t have the image on one side and the text on the other. The idea was to play with both and make the whole thing work. In fact, the text really helps to hold on to something for the poor viewer who might be lost.

GS: This brings us back to the subject of temerity and caution. If the text were written a little more freely, in a poetic way, i.e. with associations of ideas, and didn’t necessarily have a legible thread for the viewer, would this kind of mixing of images and sounds be prudent? Or would we be taking too many risks if we didn’t have a clear thread for the viewer to follow?

NM: It can be done. Here I didn’t want to leave people too much on the threshold, with no way of getting in. Even if it’s poetic, there’s still a narrative. And I wanted to tell something more or less precise. I could quite conceivably do something purely poetic, yes. But then that would be another project. But I think it’s possible. I’m not being cautious, it’s just that at some point I’m not making the film just for me. I know that people are going to watch it. I know that it’s already a rather curious object, and that it may seem a little hermetic. I’m totally in favor of experimentation from every point of view, but the question is always to what extent you want to give clues or not, or to do pure experimentation. It really depends from project to project. Here, in any case, I wanted to leave open the possibility of being able to hold on to something, because I wanted to share an emotion. It’s more poetic than prosaic.

GS: I particularly appreciate moments of graphic abstraction, specific to animation, which allow things to be said in a way that other mediums can’t with the same force.

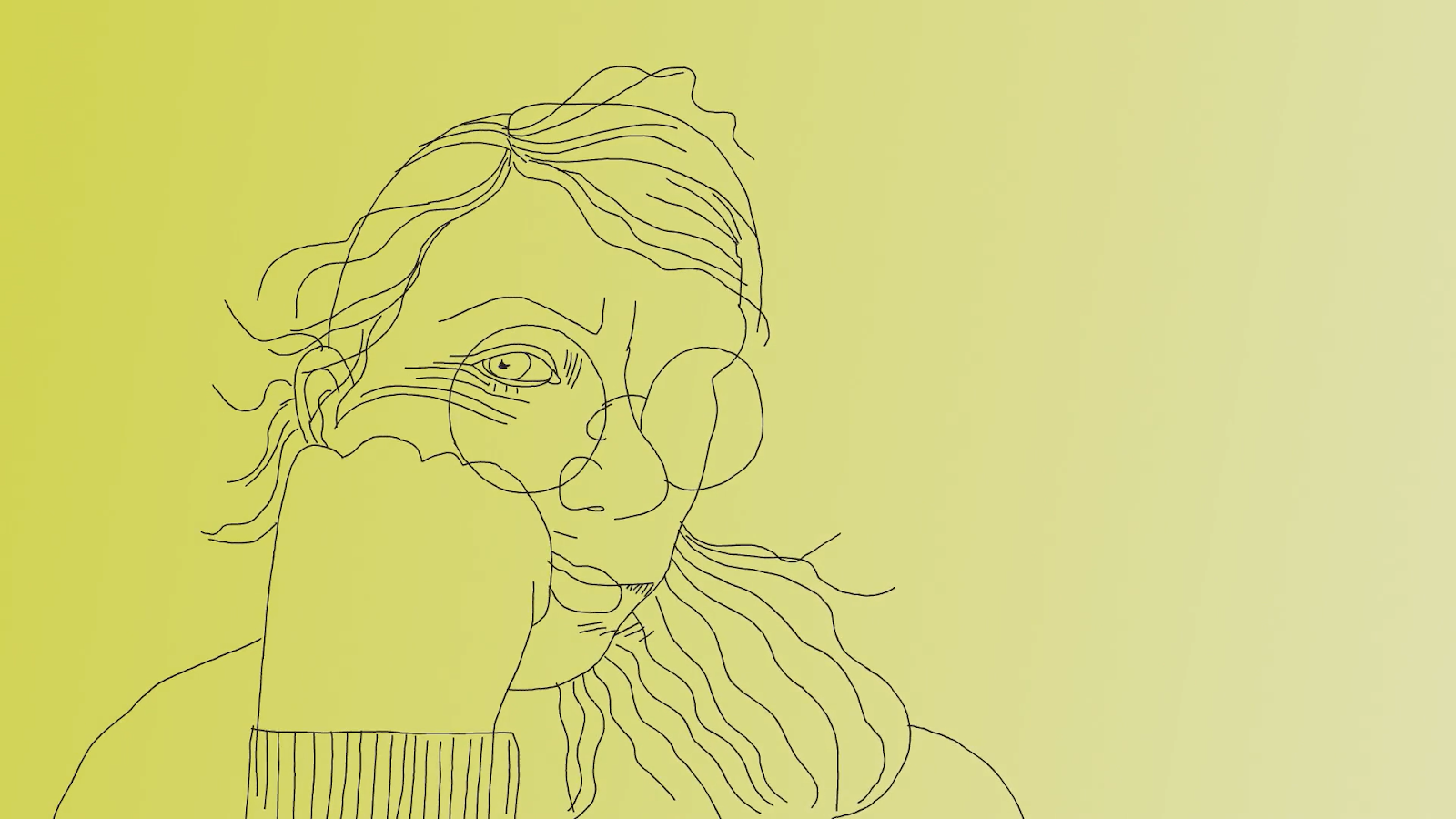

At one point in the film, the character has the posture you have now, and there’s a dilution of forms. And later, the face is dislocated with flashy, vibrant colors, like in a nightclub.

Can you comment on these passages, how they fit in and how you see them?

NM: They’re self-portraits and I wasn’t sure what place they would take in the film, but when I animated them, I didn’t premeditate the way things become abstract, distort or fall apart. Each time I started with an observation drawing, the first drawing of each of these shots, and I redrew image by image starting from the last image without reviewing the previous one. And so yes, it was more of a kind of experiment. With the animation process which is slow and repetitive, the image was deforming itself little by little and I knew I was drawing my face but at one point it just became a shape that I repeated and which I let deform like an exercise in animation.

GS: Did these scenes find their place in the film a posteriori?

NM: I said to myself quite quickly that I could put some in the film but it took me a while to find their precise place in the film. I really like painting self-portraits. It actually fascinates me because it’s a capture of a moment when in fact the creation of the image itself takes time. It gets diluted anyway and it’s a trace of something but it’s completely indefinable. It’s very curious to draw yourself. It just becomes a set of random traits and it resonated with this questioning of identity and introspection that there is in the film. There are some that I didn’t put in the film, there are some that I reworked a little bit to lengthen them a little bit in relation to the rhythm of the film. They found their place more in relation to the text and the other shots which were next to it, because they are each part of sequences.

Christophe Rault on sound was also very interested in these self-portraits and it helped him to structure things. It became a kind of pillar, in editing, to create a narrative in arcs, made up of other shots and to arrange the shots, the sounds and the parts of text that were placed between.

GS: I don’t remember there being any music in the film. Is there one?

NM: Very little. Just at the end in the last part of the film after a cut, we see the tree on the ground and the music arrives at that moment and accompanies the entire end of the film. At the beginning, I didn’t even want any music at all and it was Christophe again who came up with this music at the end. There are a lot of sounds that aren’t necessarily sound effects throughout the beginning of the film. There is a lot of sound work. It’s also narrative in its own way and at the end, there is music but there is almost no more sound. There isn’t much other sound information left besides the music and a little bit of text.

WH: You said you showed the progress of your work to someone else. I imagine it’s Johanna Lorho who gets thanked at the end.

NM: Yes.

WH: Joanna Lorho is a director that Zorobabel co-produced around ten years ago. I wanted to know if this exchange was more a form of encouragement or if it had real effects on the editing, writing and ideas.

NM: A bit of both in fact. It’s really the idea of the outside view, in fact, because when you’re in the project, there are times when you don’t really know what you’re doing. And so yes, the discussions with her gave me a little comfort in the idea that there was still something to be said with all that, because sometimes I wasn’t quite sure anymore. She saw things that I didn’t see and so that pushed me to take certain scenes a little further, to dig a little deeper into certain aspects, to structure, to find consistency.

GS: At the end of a job like this, when you take a little distance and dream of the next film, you can take stock: are there things you would have done differently with all the What experience do you have now on this film?

NM: I don’t think I would have done things differently but I won’t do things the same way again, at least for a future project. But I don’t see how I could have done it differently. I detached myself from this film. It’s always curious to talk about it again in such detail because I’m no longer in this process. I have ideas for a project but again I don’t know yet if I’m going to make a book or a film. And in any case if I make a film, I think I’m not going to write more beforehand. Not that one approach is better than the other, but I would like to try to be less fragmented in the next one, just to try something else, but not because it might fit better with what I’m trying to do.

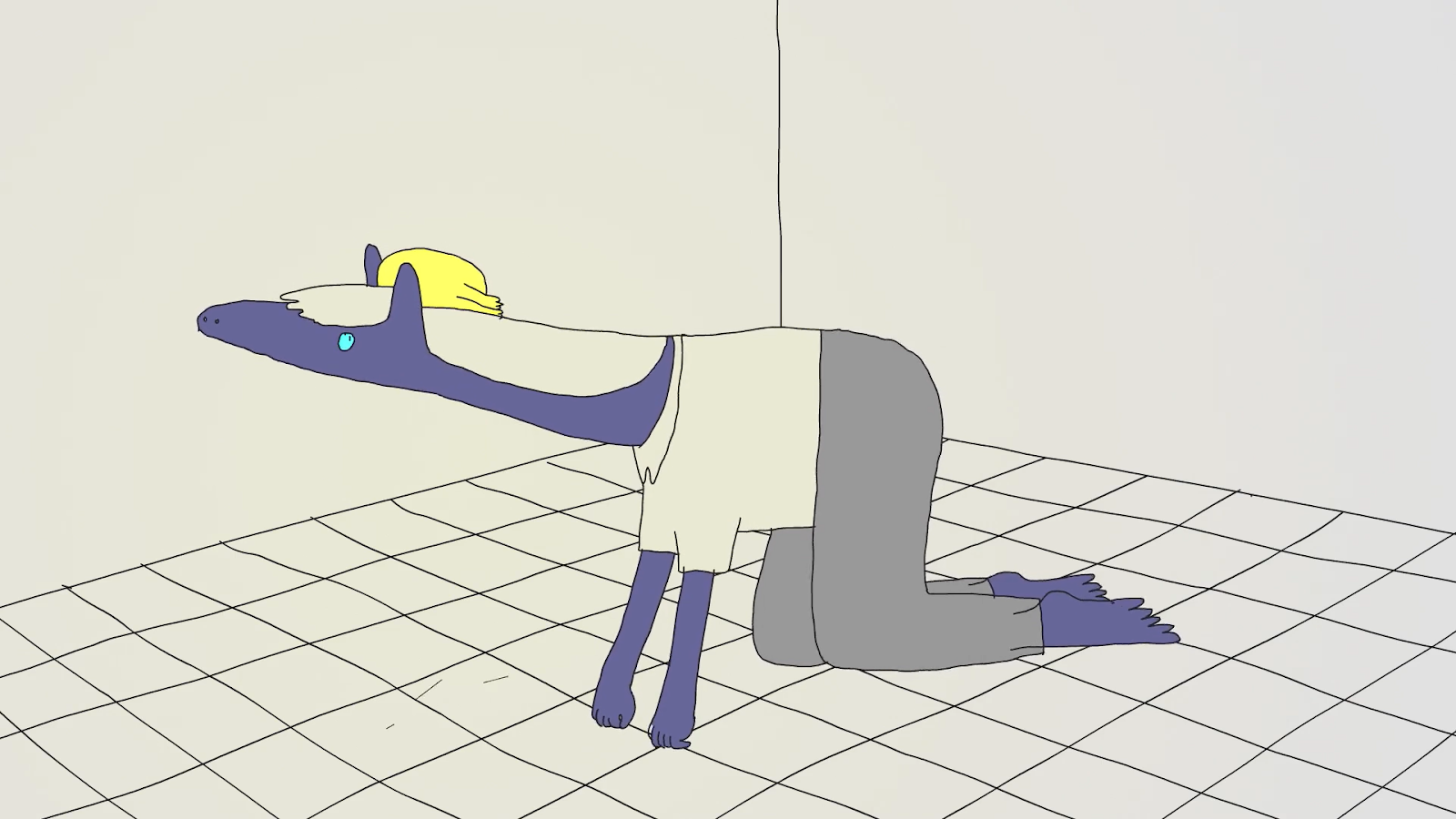

GS: Fragmentation is a word, but it is also an image that exists in the film: it is the mother who acts like a horse and breaks up into pieces and, if I remember correctly, the pieces come back together afterwards. There can be a source of fragmentation and a source of assembly. Am I interpreting correctly? Is it conscious?

NM: Yes, it’s rather positive, it’s coming together but not quite yet. We all have the possibility of having moments when we are more coherent and more put together and moments when…

Notebook extract

GS: It’s part of the specific plastic vocabulary that is actually developed in the film.

We mentioned earlier shots like that of the tree or the biker, which are not directly linked to a dramaturgical line. Nevertheless, they are there, they take their place, like impacts which somewhat condition our perception. Even if we forget them, because they are not linked to the narrative. This is a problem that I ask myself personally: how to manage what is connected and what is dislocated or fragmented so that the viewer does not get lost?

NM: The animatic or pre-editing of a film was presented like a lasagna: there was a track with all the shots, a track with all the self-portraits, a track with all the shots showing small observations of unusual things, a track with all the shots at the sea and with the child. There were several layers like that. That’s what was difficult. All that coexisted and if I could, I would have left them at the same time. But when you make a film, you have to arrange them one after the other. It was complicated to know which part of the lasagna to put after the other. I was explaining this lasagna story to Christophe Rault and that’s how we came up with this idea of arcs in the narration which helped me find the order of things.