THEORY

MASTERCLASS

WRITING ANIMATION: BORIS LABBÉ

Georges Sifianos: Can you tell us about your work, how it was conceived, your background…?

Boris Labbé: I come from Occitanie, from the Pyrenees. My Pyrenean origins may well have influenced me.

I’ve always drawn, it’s a constant in my life, even if I’m drawing less and less, because my work is focusing more and more on digital tools, but with a potential that comes from drawing.

I went to a scientific lycée and was very interested in science when I was young, as well as drawing and art. Then I very quickly decided to study art, so just after the baccalaureate I went to the Beaux-Arts in Tarbe for 3 years, where I was immersed in the context of a school that was better equipped to teach contemporary art, which stemmed from conceptual art and post-Duchamp art.

In my first year as a young student I tried out a whole range of disciplines: photography, ceramics, etc. Then I became interested in Land Art and in my second and third years I concentrated on drawing, large format drawings, 1 m by 2 m, not at all geared towards animation or calibrated for film. In fact, I didn’t see myself as a future film director at all. I was thinking more along the lines of a visual artist or draughtsman.

At a certain point I got a bit bored of my own production, and even of the teaching at the Beaux-Arts, and I needed to put that back into play. At the same time, I discovered video art at the Beaux-Arts and I also discovered animation, but from a distance because there was no specific animation course. My desire to draw and to add a temporal dimension to my drawings led me to apply to schools specialising in animation, in particular EMCA. I didn’t finish my course at the Beaux-arts, I only did 3 years instead of 5. I could have done 5, I only did 3 years, but I still got a diploma, a DNAP [Diplôme National d’Arts Plastiques] and I went to EMCA. I also applied to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Poitier, which had a digital art section. Digital art, drawing and animation were all in the back of my mind. It was the EMCA school of animated film that appealed to me most at the time. These courses are what determine you, and I probably could have done something else if I hadn’t come across them.

GS: Have you seen any films in the meantime that have interested you?

BL: I knew Michel Ocelot’s work. I wasn’t familiar with independent animation as it’s called, I didn’t know many short films. But I had seen The man who planted trees and obviously a few animated film gems and I liked them. I’d also seen what the La Poudrière school and the Gobelins school were doing. I didn’t know the EMCA school very well, they didn’t have very good communication. It wasn’t easy to find out what was really going on when I joined in 2008. When I went to take the competitive exam, I saw the profiles I had around me, I saw what was going on, and that interested me. I wasn’t a connoisseur at all, I was going into uncharted territory. I didn’t yet know Norman McLaren or pre-cinema. I had a lot of gaps in my knowledge of cinema and animation in particular.

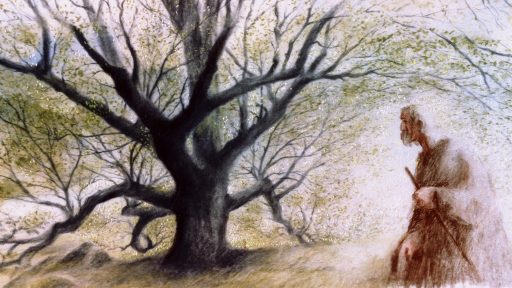

The man who planted trees by Frédéric Back, 1987

GS: Did EMCA give you this culture?

BL: Yes. At EMCA, yes. At the Beaux-Arts, there were art history courses but often the teachers themselves didn’t know much about animation either. They tended to show us video art. I was influenced quite early on by Bill Viola, who still remains in the shadow of my work when I make video installations. A French artist like Pierrick Sorin does some interesting installations, in his relationship with the studio work and special effects of Georges Méliès, who has always fascinated him. I love Méliès too.

Bill Viola

Pierrick Sorin

Georges Méliès

Everything I’ve developed in animation comes from EMCA, but I didn’t have the profile of the typical student. Some of them had gone to prep-schools to get into animation, and they were often prepared to do animation, whereas I wasn’t at all. And I did my first storyboard for the EMCA competition, I also did my first nude for that competition. They took me on anyway. At EMCA there was a director of studies, Christian Arnau, who was interested in contemporary art and wasn’t into hardcore animation either. And that worked in my favour.

GS: You’re really playing on two fronts: you’re making films and installations at the same time. In my opinion, this raises a fairly fundamental question: by its very nature, an installation is local, so it doesn’t have the capacity to reach a large audience, whereas a film, by virtue of its format, can circulate all over the world. Is this encounter with the public important to you? Is there another kind of encounter with installations?

BL: As a student, I thought I would be more of an animator than a filmmaker. But that was later contradicted by the fact that my early career as a professional artist developed more in the cinema than in the exhibition halls. The production relationship is different, meaning that you don’t talk in the same way when you’re going to make a film and you don’t talk to the same people, and you don’t have the same money when you’re getting ready to make an installation. It’s night and day. When it comes to developing installation projects, the budgets are fairly low and a bit cobbled together. It may have an impact in one museum or another. When it comes to film projects, in France we have a very consolidated industry and we manage to have sufficient budgets to do interesting things. The production relationship is very different. As far as audiences are concerned, I was quick to show my short films internationally. By the age of 24-25, you could say that I already had an international career. It’s true that the film format explodes careers. If I were a sculptor, I wouldn’t have had an international career from the start. A screening in Annecy with 1,000 or 1,500 people seeing the film all at once gives you access to what you might call a ‘mainstream’ audience. But, at the same time, the short film audience is made up of specialists, it’s a bit of an animation niche, as some people call it, and we often find that, from festival to festival, we see the same people again, we discuss the projects in the same way… and we also find it hard to reach the press or the real general public that we only reach in the feature film format. Even so, it’s hard for ordinary people to get through the doors of local cinemas and festivals.

My approach as a video artist, outside cinema, complements this first approach, that of making films and showing my work in the field of cinema. Showing a project in an exhibition is a way of getting animation out of its usual place, which is usually the animated film festival, and confronting it with an audience that is completely unfamiliar with animation and could in fact be considered as the ‘general public’. It’s an average audience, sometimes more or less keen on art or contemporary art. This allows us to meet a different audience, to talk about our projects in a different way, to build bridges between visual art and cinema and also to present an art of animation that is not cinematographic. Because obviously animation exists and can exist outside the cinema.

* At the end of the exhibition in Paris at the Drawing Lab, there were 2,113 visitors.

Ito Meikyū installation (detail) at Drawing Lab in Paris, 2024.

We speak differently depending on the medium we choose and the audience we’re aiming for. This project, which was exhibited at the Drawing Lab in Paris, was the subject of a nice article in Libération and Beaux-Arts Magazine, something we don’t get in animation, even though it was selected 5 or 6 times at Annecy. It’s a way of pushing our work further and showing it to other people.

GS: You mentioned the theme of solitude. In your films, we can see a cosmogony, models of cosmogony, as in Orogenesis. In all your films, there is an interest in the idea of birth. There is often a mise en abyme. There is an abundant constellation of figures activated by a repetitive, looping action. What are you looking for in these looped actions? Are they determined by chance or by dramaturgical considerations? Do these interactions build a narrative? Is it simply a question of musical and rhythmic organisation?

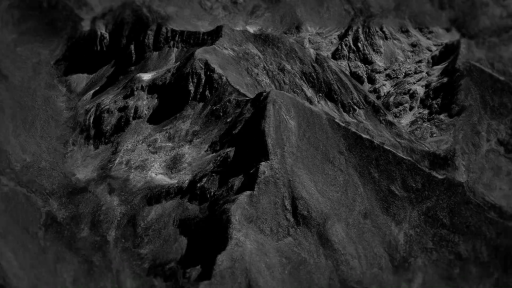

Orogénesis, 2016

BL: In this work, birth is really important as a symbol and as an act in the creative process. When we say creation, we are creating, so in a sense we are giving birth. I like the idea that the creative process is itself an image and a mise en abyme of the living world or the world of ideas. Because ideas emerge through connection, through interweaving. It gives rise to ideas in a seminal way. In all my projects, this motif of things that emerge, the emergence, growth and decline that often go through a crisis phenomenon, which will lead to a new growth phenomenon. There was a question about the philosophy behind the project. With the idea of the eternal return, of palingenesis, of the fact that things are eternally renewable, through the movement of animation and the creative movement, we are always trying to get back into the game, to find a form of positive movement which is that of creation, rather than being absorbed by negativism. Even though a lot of people describe the films as quite black and pessimistic, that’s all there is to them. They are quite contrasting films.

Orogénesis, 2016

GS: Sometimes there’s a touch of humour, like in Orogenesis, with the link to knitting.

BL: I’m not sure that this film came from a desire for humour. Let’s just say that, on this project, humour is at the beginning and the end of the project. The beginning of the film looks like a slide show, which is the negation of cinema, it’s frame by frame that doesn’t move. The first time we showed it at Annecy, the audience gasped for breath during the first minute because they thought the film wasn’t working.

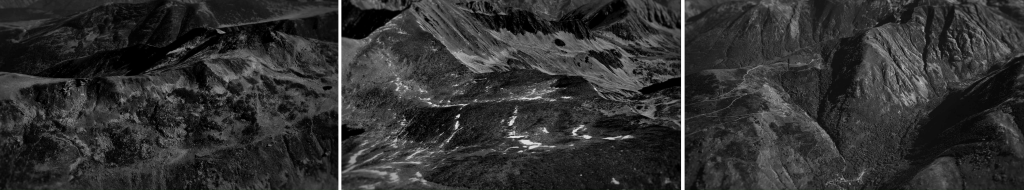

Orogénesis (the first 3 shots), 2016

It’s just that my father is a mountain guide and, when I was little, he used to make slideshows of his photos at home. It’s a personal connection.

The allusion to weaving, knitting and fabric is not so much humorous as conceptual: the interweaving, the interconnection and the compositional effect of full and empty zones… The more I progress in my practice, the more I come across this idea of weaving.

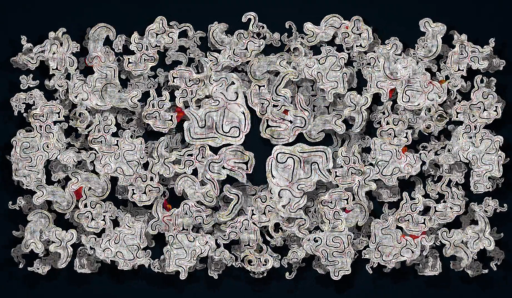

Particularly in the virtual reality project, Ito Meikyū, Ito is the thread and Meikyū is the labyrinth. In French, I’ve translated it as Fil d’errance (Wandering thread), so the image of weaving, thread and fabric, either as an image of existence or as all the work I’m also doing on fractals. A fabric is also a fractal, so from the moment you repeat a motif, it tends to behave like a fabric. Ito Meikyū‘s idea peddles the idea of text as textile. This creates lines, threads or ideas that are increasingly inserted into my artistic project. As well as the idea of the fold, of folding.

Ito Meikyū, 2024

GS: How do you choose the action modules?

BL: There’s an element of chance in my work. And each project develops a theme that guides me. In Rhizome, the theme is the creation of life, which combines Darwin’s vision with that of Deleuze. The little cells that develop are quite simple: at the beginning, little spheres that are the stem cells begin to differentiate along three different lines: vegetal, organic and mineral.

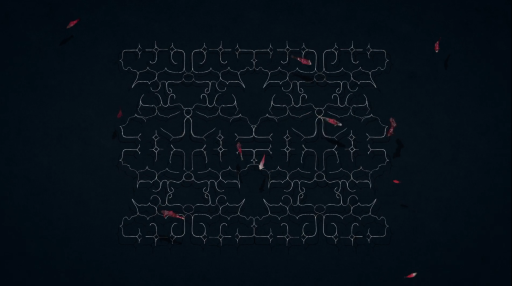

Rhizome, 2015

The mineral branch will create architectures, the organic branch, animals and the vegetable branch, plants. Everything mixes together and creates new chimeras. At the end of the film, it all mixes again and creates colour. It generates abstraction and regeneration. All these cells correspond in a sense to the development of a programme. It’s procedural but handmade. Everything mixes together organically, even if I had planned this idea of mixing the different materials, like a chemical reaction, they are at the same time dedicated to the chance of drawing day after day and dedicated to our ideas as animators. We mixed the shapes, making them mutate and transform, with a base of shapes created from research into shapes that could be animated. But their arrangement is quite random. In Rhizome, there’s a play between cellular form and globality, and that’s the strength of the film and its relationship to migration: everything migrates and mutates, moving from the micro to the macro and the gigantic. In the end, it’s the film that begins to mutate.

Rhizome, 2015

La chute (The fall) has a stronger relationship with painting through different references: Botticelli who illustrated Dante, by Goya, by Henry Darger and others. All these references become a corpus and are arranged. The shapes are not necessarily arranged in a linear or didactic way; it has more to do with a surrealist approach, that of collage, which brings chance into play. But a chance that creates symbolic and narrative dynamics. La chute is a narrative film: at the beginning, the plants are linked to human forms that mutate and become monstrous. The plants themselves become carnivorous and begin to devour characters. This produces a dramatic effect. The birds are a representation of angels who are both birds and insects. This is an ambiguous intersection of scientific and artistic imagery. An ambiguity that generates different discourses within the same film. The line isn’t very clear in terms of meaning, but maybe it generates a lot of meanings.

La chute, 2018

William Henne: La chute is probably the film that comes closest to a classic animated short. There’s almost a play on words in the film, obviously because of Dante’s circles of hell and because of these loops and animation cycles. And it ends in a spiral. Which ties in with the symbolic dimension you were stressing.

La chute, 2018

GS: You don’t necessarily want us to draw a definitive conclusion about the meaning, but there are still motifs that produce meaning.

If you don’t mind, I’d like you to develop the formal aspects: you use a number of figures, such as repetition, symmetry, mise en abyme and random camera movement, which can also be found in musical composition.

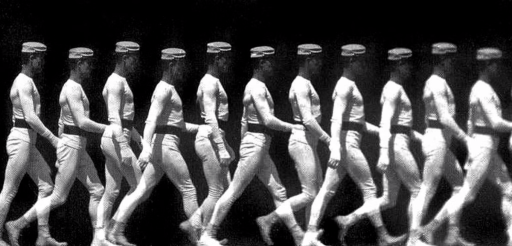

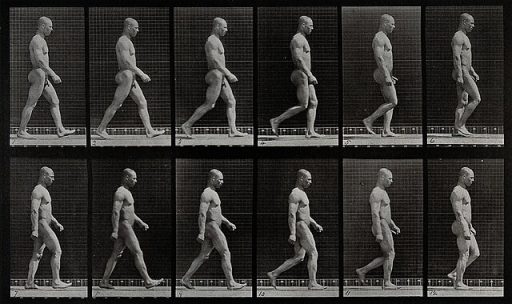

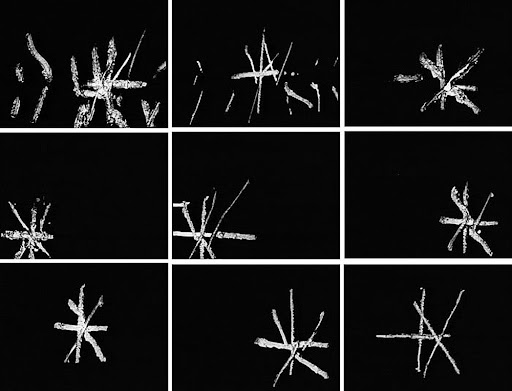

BL: As soon as you learn to animate, the first time you do something you make a loop. Animation and looping are almost the same thing. You can obviously learn to do things other than loops, but I think that the beginning of animation, and even of cinema as a moving image, is through the loop. The analysis of movement by Étienne-Jules Marey or Muybridge focused on walking, running and so on. In my artistic project, I always have 100 or 150 years of animation in the rear-view mirror. If I had started work in 1905, 30 or 40, I would have done the same thing because it was already there.

Marche de l’homme by Étienne-Jules Marey, 1886

A man walking by Eadward Muybridge, 1887

Philosophically, it is the symbol of events that repeat themselves and of the eternal return. It’s the dramaturgy of humanity, but not only that: there are many similarities with the biological world and with the movement of the planets.

In my artistic project, I sometimes feel stuck because there’s not just the loop, there are stable systems and chaos theory, which is very difficult to bring into play in an animated film and with drawings. To create chaos, you have to use digital tools.

GS: I’ve noticed that your loops are not systematic: for example, a character performs an action, then waits, then starts another action. There’s a plethora of characters and actions that allow the viewer to get lost. It’s an organisation of chaos.

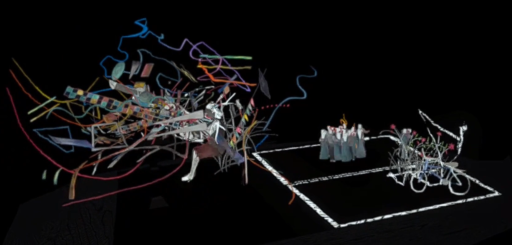

BL: Yes, I work with canon loops, like in music. Rhizome is a very good example: at the beginning, the first little spheres loop for half a second. Then they duplicate each other and begin to loop for a second. Then 2 seconds until 4 seconds. At some point, in this profusion of shapes, animations lasting between one and 4 seconds interact synchronously and sometimes asynchronously, like a cannon. When I was animating, I used to calculate when certain characters were going to interact every second or every fourth time. This creates machinery. I create machines, my films are close to automaton theatre. I create little machines that work together, and working in canon simplifies things formally, otherwise it would be too complicated to understand what we’re doing. If there are loops of different durations, that poses a lot of problems; errors sometimes creep into the programme, into the manufacturing process. And it poses a lot of problems in terms of sound when you want to synchronise things, when you want to create harmony and rhythm and everything is arrhythmic. That’s where the idea of the canon and the function of tempo came from quite quickly.

Rhizome, 2015

GS: This brings us naturally to the musical dimension. What is your relationship with music? Do you play music? The approaches you take are often close to musical composition.

BL: I played the piano when I was young but I’ve forgotten all about it. Honestly, that’s not where my work comes from. But I do listen to a lot of music.

When I started making my first films, I did the sound, as in Kyrielle and Ils tournent en rond. When I was a student, I started asking a friend who does sound for films like Cinétique for sound design. For Caverne, I worked on pre-existing music by Didier Malherbe, a French composer who is fairly well known in experimental jazz. I don’t really have any training in sound and I quickly felt limited, so as soon as I left school I stopped making my own sounds, preferring to collaborate and seize the opportunity offered by cinema and the audiovisual sector to meet and share the creative process, the creative territory, with other people, particularly composers.

Didier Malherbe (photo : Niquette Malherbe)

One important thing: at one point I listened a lot to Steve Reich and minimal repetitive music. I tried to analyse it and understand how it worked. Steve Reich does the opposite of what I do, he creates loops that desynchronise and resynchronise.

Caverne, 2011

GS: The phase shifting…

BL: Yes. I’ve never reached that stage of creation. In animation, it’s difficult. It’s feasible and the idea of phase shifting is interesting in that it creates a tremor: at the moment when the notes fall right, it creates this constellation and this explosion.

I was lucky enough to do my first artist residency at Casa de Velasquez in 2011-2012, with composers in particular. There I met Daniele Ghisi, a composer with whom I work a lot.

Daniele Ghisi (photo : Ersnst Von Siemens Musikstiftung)

Aurélio Edler-Copes, among other things, created the sound for Rhizome. Most of them came through Ircam, so they come from experimental and acoustic music. I found that I had a lot in common with them, particularly from a research perspective, in terms of the experimental dimension and a vision situated between tradition and innovation, which sometimes manifests itself in the use of digital tools.

Aurélio Edler-Copes (photo : Aurélia Bertol)

I have a lot in common with Daniele Ghisi, who is also interested in early music, the music of the Middle Ages, which he brings back into play with his digital tools. He is also a mathematician and programmer and creates software and tools to transform sounds in his own way.

I like the idea that the artist is also a technician. I’m not an engineer, but I like prototyping and producing creations that are out of the ordinary. And this is achieved by working with materials and digital technology.

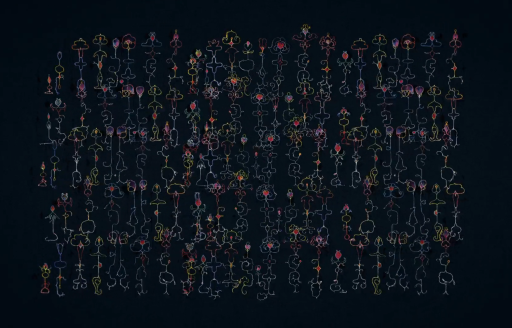

WH : In the Sirki film series, the link between the music and the image is the most obvious, not only in terms of rhythm but also at the level of the layers, those of the compositing that resonate with those of the voices. They work together. The music is by Marewrew.

Kaparamip (Sirki), 2019

Ciciri (Sirki), 2019

BL: It’s Ainu music. This project was commissioned by the city of Sapporo. I went to Hokkaido in northern Japan for a residency. Right from the start of the residency, I asked them to allow me to do a residency based on sound research and the creation of Ainu sound. Repetition is not just a modern phenomenon, it’s part of the shamanic tradition. In the Sirki series, I linked embroidery motifs from Ainu kimonos, which I revived, with the repetitive sound of the canons of traditional Ainu songs. The Ainu language has no written tradition. This is a form of homage but also a work of conservation. One of the songs is about a child learning to walk, another is about cutting up a whale (the Ainu have been whaling since ancient times. They were reputed to be great hunters).

Marewrew (photo : Hiroshi Ikeda)

WH: The reference to fractals is also the most obvious in this series through the systematic zooming out. It doesn’t necessarily work like real fractals, where normally there is a similarity of pattern at different scales. So it’s more an evocation of fractals. In one of the episodes of the series, Tetarape, the zooming out is such that it creates a moiré effect and brings out a new pattern, generating pattern on pattern.

Teratape (Sirki), 2019

BL: Mise en abyme produces a new type of composition and that’s something you find when you’re making a film, you can’t really plan it in advance. It’s a way of taking the process and conclusions of a film like Rhizome and applying them to simpler, much shorter films, with more precise motifs at the same time. It’s almost a subject for study.

We haven’t talked about the camera in terms of the idea of zooming out, which is a recurrent feature in my cinematographic language because it obviously allows elements to fit into the frame. This idea of multiplying and adding is important. The frame doesn’t really exist, there’s always something outside the frame. By using digital tools and the virtual camera, we quickly realise that cinematographic space is potentially infinite because the virtual world has no background. The virtual camera speaks of the infinite depth of virtuality. I use the camera in a rather free-floating way. It can walk through walls, it has no physicality, it has no body, it is disembodied. It is omniscient.

Rhizome, 2015

GS: Disembodied or individualised? This device, which functions like a free electron without perceiving its limits, which represents the camera, is perhaps the individual in the end. You make a choice in the chaos.

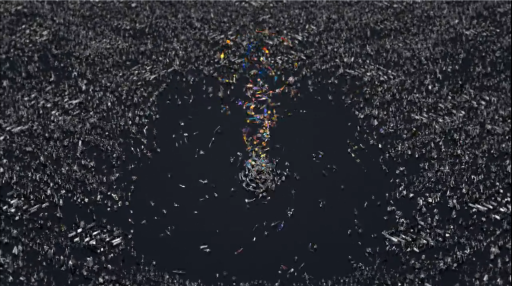

BL: The camera is above all a dramaturgical tool as far as I’m concerned. If, for example, in Rhizome, the same panorama lasted 2 minutes, 20 minutes or 1 hour, it wouldn’t be the same film. So it’s really the camera that makes the film. The situation develops with a given timing, with a given dezoom, and all that creates the film. In La chute, with the back and forth of the camera, with those great panoramic movements, it’s the camera that makes the film and it’s the camera that makes the filmmaker. The same animations projected in a museum would have produced something completely different. I’m not sure that the camera represents an individual; the camera is more precisely de-individualised. It is a vision that is often external to the world. It creates the space of the cinema frame like the idea of the window. It separates the audience from the virtual world or the world of the film, inside the film. In my opinion, it’s more a tool than a personification.

La chute, 2018

However, this is contradicted by the virtual reality project, Ito Meikyū, because in virtual reality, the viewer is the camera, he’s the center of the world.

Ito Meikyū (spectator)

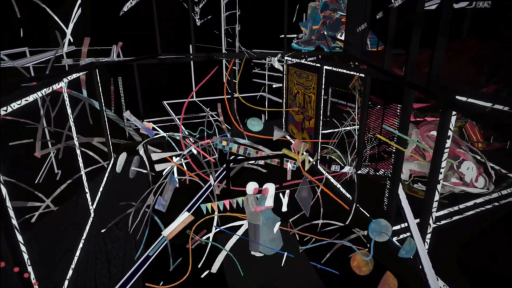

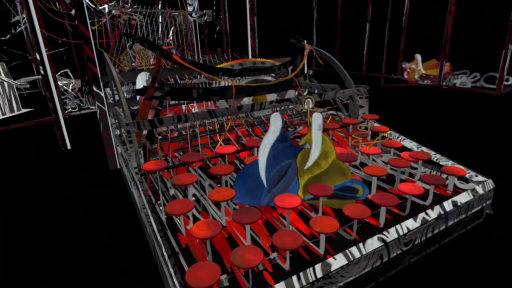

WH: I was lucky enough to experience the Ito Meikyū installation in Paris. In the virtual reality part, the viewer is in a 2D-3D relationship. We circulate in a three-dimensional space where we come across punctual 2D animations. And the formal solution for integrating these dimensions lies in the fact that the constructions we encounter are open structures. This also makes sense, as we gain access to the interiors of the dwellings and the intimacy of the characters. So much so, in fact, that to view some of the interiors and animations partly hidden by the structure, we have to bend over, engaging our own bodies, making us a kind of voyeur in relation to these intimate scenes that go round and round.

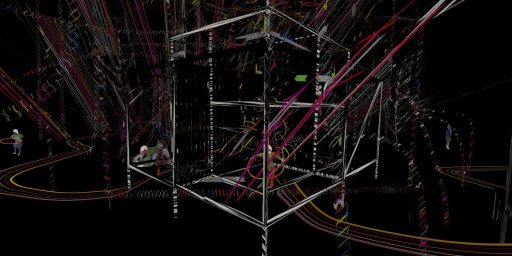

Ito Meikyū at Drawing Lab in Paris

Ito Meikyū, 2024

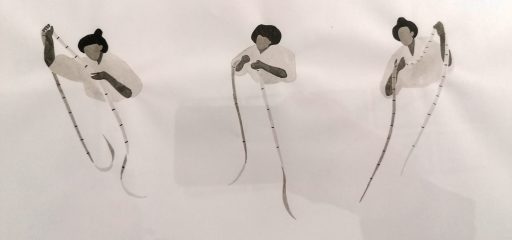

The tour is not identical for every viewer – it’s interactive – but for me, I ended the tour in the room dedicated to the history of cinema, where we move from pre-cinema to digital tools, with, among other things, a projector overlooking a movie theater. We see an animation of seamstresses viewing film, as seen in the preparatory sketches and drawings on display at the exhibition entrance. The virtual reality experience is incredible.

Ito Meikyū at Drawing Lab in Paris

Ito Meikyū, 2024

BL: This installation sums up my practice as a filmmaker, visual artist, video artist and draughtsman in a single project.

The whole process I’ve just summarized, from references to pre-cinema to today’s digital tools, is reflected in this project and, in particular, in this room, which is a bit like a secret passage. You can even see a film in here, which is one of the final scenes that can be seen elsewhere in the tour if you make it that far.

Ito Meikyū / Fil d’errance published by Drawing Lab for the exhibition

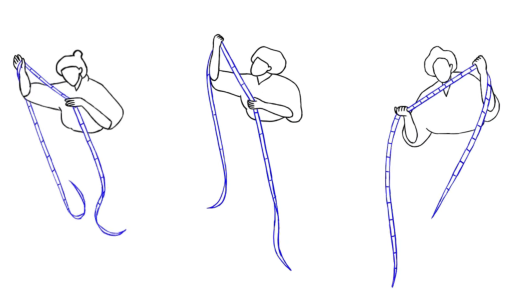

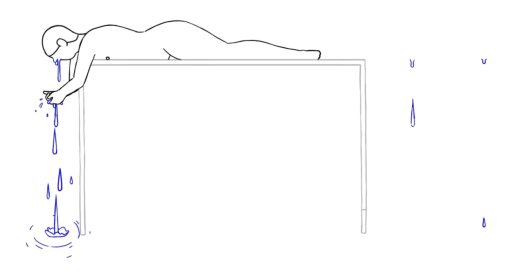

Ito Meikyū, line test by Capucine Latrasse & Agathe Sollier

The place of the user or viewer in a virtual reality work is obviously completely different from that of a film. You put your body into play. You play. As a creator, I play with the viewer’s body by placing him or her in certain situations and spaces. In one place, they’ll have to bend over or take a step to the side in another. The spectator feels inside. This brings into play the idea of presence, which is not a dimension I’ve dealt with in cinema. We know that the audience is present in the theater. You can play on collective effects like humor, when the audience laughs. But for my part, so far I haven’t played on the audience’s presence in my films. Video installations, on the other hand, play with circulation, displacement and space, as in Monade, where you move from one side of a tulle to the other.

Monade, exhibition at Cinémathèque québécoise, 2022

Virtual reality is interactive, so everyone doesn’t have the same experience. There are several experiences in the same work, which becomes multifaceted. A bit like what you find in a film like Rhizome, where some viewers follow one character, or some, other characters. I’ve always wanted to offer different possibilities in the same film. The profusion of images means that our brains and our attention aren’t able to capture everything from a single point of view. We’re in a garden in which we pick certain elements without being able to pick everything. This idea of missing certain things, in an overflow, is always present in my projects. In virtual reality, there’s always an off-field or a door you haven’t taken, so you know you’ll always have missed something. This creates a little frustration and, at the same time, a fascination that leads the viewer to either return or share their experience with someone who has had the same experience [Editor’s note: there are two VR headsets in the exhibition]. One has seen the movie theater, another the weeping scene, another the scene with the fetus and the large female body, yet another the weaving scene with a violent sewing machine. All this creates a series of emotional and narrative possibilities.

Ito Meikyū, preparatory drawing

The 2D-3D solution was not at all easy to find. I come from 2D. The solution was to open up the spaces. The architecture and trees become lines. The plant and architectural aspects draw the space, and the volumes are not illuminated but simply textured. Texture is drawing. They thus have a very close relationship to 2D characters, themselves caught in multiplanes, as in Disney’s multiplane title-bench. Certain elements interpenetrate, such as crumpled or twisted papers that become volume. 2D becomes volume.

Ito Meikyū, 2024

Éthann Néon: In the video for the installation, Ito Meikyū, I noticed that there were some animations from previous films that came back, notably Kyrielle, even older ones. You often reuse animations from previous works, and this was only the case for Ito Meikyū.

Kyrielle, 2011

BL: I’ve been doing this for a few years now. The first time I went back to a previous animation was as part of a project with Angelin Preljocaj, on Swan Lake, simply because he was interested in some of my films, and I did a version of Orogenesis. This had both a practical aspect, because it allowed me to create something more easily in a hyper-complicated project, because the ballet lasts 1h50 – I worked on it for 8 months, it wasn’t easy – and it also took the pressure off me to have a kind of sacred filmography. Why are pieces that have been around since 2010, 2011 or 2012 no longer being released? There are films that we don’t watch any more, and that I don’t show any more either. Still, they’re part of my career, and in a project like Ito Meikyū, it lends itself to that.

Le lac des cygnes by Angelin Preljocaj (photos : JC Carbonne), 2021

I also made a few reuses in the Glass house project. It allows me to stage my own personal museum. Ito Meikyū is a kind of virtual tour of an imaginary museum in which I put everything that interests me. The children’s play scene is a reference to Kyrielle. There’s a rather violent scene that could refer to La chute. Other scenes are reminiscent of Rhizome. I use similar techniques, in this case animation. As I said at the beginning, it’s all about re-engaging, re-doing – the eternal return – I’m doing the same things over and over again, and I’ll be doing them all my life. That’s the drama of my life [humor]. But trying to remake while moving forward – it’s more like a spiral.

In Glass house, I reused certain structures, or architectures – similar to Ito Meikyū by the way – and I also reused an old project called Danse macabre. I build bridges between different projects. On the other hand, I always change these borrowings, I don’t use them as they are, I make versions.

If I go back to one of Deleuze’s titles, Difference and repetition, it’s really that: how to recreate something differently again with the same thing.

Danse macabre (detail), 2013

Glass house, 2023

ÉN: How do these philosophical concepts – cavern, monad, rhizome… – enter into your work? Do they pre-exist? Do the inspirations come from philosophical readings, or do they arrive during the process, or even after the fact?

BL: When I was studying fine art and then animation, I had fewer references, I was more naive. It took me a while to read Deleuze. But I’ve been reading and researching for ten years now. At the time of Kyrielle, I hadn’t read Deleuze. Friends advised me to read Rhizome or Borges et cetera. I started reading all that late in life. These readings were a new springboard. We’re talking about something very personal, and as the project progresses, I try to discover new works and authors and create a new breath, a new desire. And philosophy helps me do that. These are all subjects of study for me.

Rhizome was a direct reference to the eponymous chapter of A Thousand Plateaus by Deleuze and Guattari.

Rhizome by Gilles Deleuze et Félix Guattari, 1976

La chute didn’t necessarily have a very strong philosophical background; it’s more like Dante, which is already very profound.

For Monade, I went back to Deleuze’s The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque. Deleuze is often not far away. I particularly like Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation, a reading of Francis Bacon’s work.

And if you look at Ito Meikyū from Francis Bacon’s perspective, there may be something…

Logique de la sensation by Gilles Deleuze, 1981

Zepe: In Journey to Mexico: Revolutionary Messages & The Tarahumara, Antonin Artaud points out that if we were to speed up the movements of the clouds, it would look exactly like the dance of the Indians during their ritual. Do you think that everything repeats itself in an immense universe of forms, from which there is no escape?

I thought of a drawing by Escher, which I imagine you’re familiar with, with a chess game: at one point, he sets up a rupture, i.e., everything topples over.

Jeu d’échec by M. C. Escher, 1940

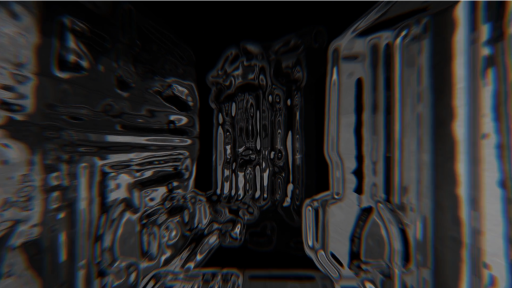

In Free radicals, director Len Lye creates loops. In a lesser-known film, Particles in space, dots generate a succession of looped shapes, then Lye establishes a state of rupture with no link to what has gone before.

Can you conceive of a device in your work that would break with all that, using all that digital technology allows in terms of repetition, motif and filter?

I get the impression that you’re fascinated by closed systems which, even as they evolve, transform and expand, always end up in a closed space.

Free radicals, de Len Lye, 1958

BL: It’s the battle between order and chaos. Creating chaos, randomness, in animation, by hand, with drawings or this kind of tool, is extremely complicated, if not impossible. It’s a mathematician’s approach, creating an equation that doesn’t create repetition, that’s always shaking. The computer can do all the simulations – spheres, clouds… – and explore what would be out of control. I just can’t do it. I’ve thought about it several times, of course. I can make loops, I can break loops, but then either it leads to a new loop, or the animation collapses and I go on with another loop. It’s always a closed circuit. When it comes to drawing, I don’t have a conceptual or even a technical solution for exploding this. I’d have to watch Len Lye’s film. With the computer, you can do it. I’m trying to get closer to it: particle systems, random animations and so on. In Any road or Glass house, I play with artificial intelligence.

Any road, 2016

GS: In Metastasis, Xenakis tried to reproduce the movements and propagation of sound during demonstrations.

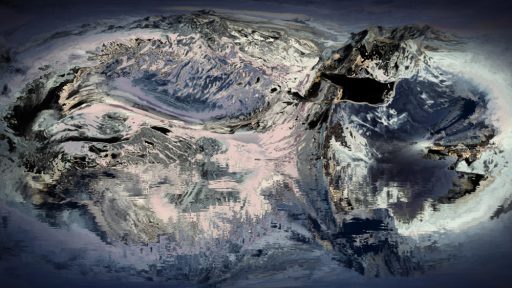

BL: A film like Orogenesis proceeds from chaos all the same. The mountains weren’t animated frame by frame, knowing exactly what would happen. The film plays on the control of chaos to make it fit into a film. I could have experimented a lot and got to the point where I couldn’t even shoot that. As it happens, I succeeded. I made a first attempt that didn’t work, so I gave up for a year and a half and did it again.

In my project, there’s this ambivalence: closed systems, confinement and machinery are important themes. I’m well aware that this is a rather simplistic view of the world, because the world isn’t made up of machines. Rather, the world is made up of a succession of stability and instability. I’d like to be able to signify that or get close to it. Orogenesis was one such attempt. I’m not saying it succeeded.

Orogenesis, 2016

Z: When we work with artificial intelligence to write a screenplay, we input all the data and the system makes proposals by playing with what exists. But it’s often prevented from moving on to another level of interpretation. In other words, it always manipulates what already exists. He may even come up with ideas that would be fairly conventional and that could be written by other screenwriters on the same subject, but the problem is that it doesn’t offer any disruption. Len Lye’s film proposes a state of rupture.

You were talking about Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation. When a painter paints, he accumulates layers and, if he paints with a certain intensity, there can be states of rupture.

BL: Bacon painted in the dark or, at any rate, tried not to look totally at what he was doing. He used traces, the unexpected, he tried to avoid figuration, and Deleuze puts forward the idea of sensation, of getting out of the figure. But that’s extremely difficult! My approach is to create a tension between figuration and abstraction, both of which are present in my artistic project. There’s a crack that happens between the two. When a form, even in a narrative film, suddenly leads to an almost totally abstract scene, it creates this formal and even emotional rupture. We can no longer hold on to the symbolism that the figure may have embodied. Abstraction becomes a symbol in itself: black, white, color, assertive, fluid. This has a huge influence on the way it’s received. That’s where I make a break. There’s a break between classical cinema and experimental or even visual cinema. Within the same film, I don’t think I’ve made a complete break.

Le lac, 2021

GS: How did you go about working with the orchestra on Glass House? What preceded it: the image or the music? For Le lac, were there any concrete specifications from Angelin Preljocaj?

BL: Glass house is a kind of commission, a commission and carte blanche at the same time. The music came first. Lucas Fagin, the composer, contacted me a few years ago, saying he had a concert project with Ensemble Cairn that he wanted to accompany with a video. It lasted 40 minutes. I saw his psychedelic sci-fi universe and liked it. We got on really well and he told me I could do whatever I wanted. I pulled out the Glass house project from one of my drawers, in my computer. I showed him the Glass house project, which was originally a film project, but which I wasn’t sure how to turn into a scenography.

For the record, there was a screenplay by Sergei Eisenstein called Glass house, which inspired me to do the project.

Glass house – Du projet de film au film comme projet by S. M. Eisenstein, Les Presses du Réel, 2009

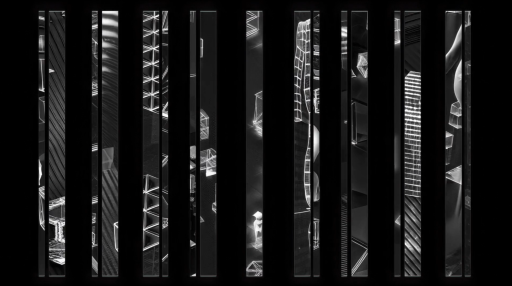

I adapted this work to the project, which was a concert. But I was very constrained by the music, because creation is first and foremost musical, and I received, as the creation progressed, MIDI-format mock-ups of the music, to which I adapted acrobatically. It was like ping pong with the composer. The temporality, and the fact that there were nine parts, came from the music. And so did the stroboscopic, highly-chopped aspect of the sound. I usually shoot long, fluid shots without too many breaks. It took me a very long time to make cuts in my films, almost frame by frame, it’s really radical. In Glass house, there are cuts everywhere. The concert took place twice, and a year later I adapted the project so that it could also be a film. It’s a bit the other way round: we took the recordings and changed a few compositions and videos to make it look more like a film than a stage design.

Glass house (concert), 2023

With Preljocaj, on Swan Lake, it was a video set design, it was more of a decor, I had a mission as video decorator for a 1h50 ballet. The brief was to respect the choreographer’s vision. We transposed Swan Lake to a modern period. Instead of the usual palace in the first act, it’s a city scene that resembles New York. In the second act, the scene on the lake becomes a scene under the lake, underwater, with a factory on the lake, because the choreographer wanted to add a capitalist and ecological dimension to this fable. The challenge was to ensure that the animation didn’t overpower the dance, because as it happens, the large-format video projected onto the stage is very powerful. When you put a video behind dancers, if it’s too powerful and gripping, the spectator stops watching the dance. And from time to time, the choreographer has rapped me on the head to stop me taking up too much space, so that I stay in my place, that of the set designer. So the video sequences are very slow.

Le lac des cygnes, 2020

I adapted these videos into a video installation in the form of a diptych, which is now called Le lac (The lake), in a completely different set-up than for a theater, with a new sound creation.

It’s true that it was a rather constrained creation, with a constrained subject and a constrained timing. But it’s always a way of moving forward and testing things out, of entering someone else’s universe to try and find yourself in the other person’s work.

Le lac, 2021

GS: Glass house is different in plastic terms from other films, such as Kyrielle or La chute, which feature drawn graphic elements, with a human touch that can be felt emotionally. In Glass house, it’s hard to guess how it was made. Yet the effort required to make a film has dramaturgical value. In classical cinema, we know the famous principle character/objective/obstacle: a character has an objective, he makes an effort and we identify with him to overcome the obstacle. The same can be said for a drawing: a drawing moves us because we see in it a struggle with matter, with form. A drawing may be a failure, but if it’s a success, it moves us. On the other hand, when we can’t make out the effort, because it’s a mechanical process, even if it’s a technological feat, we may not feel emotionally involved.

BL: I like doing things by hand and also not doing them by hand, I like both. If, for example, you establish a relationship of difficulty between Kyrielle and Glass house, it’s much more difficult to make Glass house. Kyrielle is a project that took me a month and a half to complete, with 300 drawings. Glass house took me almost a year. On top of that, there’s an element of research into unfamiliar tools. The character/goal/difficulty scheme works in a film, but not as a filmmaker. Audiences see films and are either touched and interested, or not touched at all. Personally, if a filmmaker has spent 10 years making a bad film, I don’t care. Too bad for him. Whereas if he’s spent 10 minutes making an incredible film – it can happen, I can’t do it – I don’t mind, as long as the project touches people with what it says and what it develops. I like the labor of animation or drawing, and I also like to see when filmmakers commit themselves to a technique by sticking to old-fashioned manufacturing. I like drawing on paper because I’m not good at drawing on a tablet. I like the materiality of drawing, feeling it and using inks and water, playing with dilution and superimpositions. I don’t do it to add value in terms of working time or difficulty. I do it rather to bring a craftsman’s touch that you can’t get with a computer, with those imperfections and that material that you can’t reproduce, at least until now, with a computer.

Glass house, 2024

GS: Let’s imagine that someone draws a perfectly straight 2-meter line by hand, using a pencil, and let’s imagine the same line produced industrially. The first line moves me emotionally because of the performance of the artist, of the executor, it’s a tour de force, while the other leaves me indifferent because it’s mechanical. In Glass house, despite the fact that you spent a lot of time, I didn’t really have any information on the effort it required.

BL: It’s not all automated. But I understand. We’re obviously not affected in the same way if a calligraphy is done graphically by hand or with a printer. The human act and the craft induce a personal and direct relationship with the artist. In the context of a film, this aspect is less present than in a contemporary art space, where we can have an explanation, a mediation on the fact that, for example, this artist has created a 2 km line with a pen. The artist’s act and method are interwoven into the artistic project. When you draw a 2D project, or make a stop-motion film, it’s also interwoven, but less so. We talk more about the emotional quality of the film. Otherwise, we’d be making the opposite argument, that is, pitting traditional techniques against new ones. Even for 3D, which is no longer a recent technique. The film Flow, which did well in theaters, is a technological feat, but that’s not what people are talking about. The same technological prowess at the service of a – quote-unquote – “bad” film, people would say “too bad, here’s a failed film”.

WH: There’s an ambiguity in Georges’ question. In certain animation circles, there’s a desire to feel the author’s sweat, which is a form of romanticism that’s uncorrelated with the quality of a film. In Glass house, we see the typical processes of what we’ve seen in recent years with “artificial intelligence” tools, which are fed with a whole series of photos, with a corpus of images that we can more or less control. So, yes, the automated aspect is more prominent in Glass house.

BL: Yes, Glass house is more disembodied, it’s a dystopian project about the use of technology and the glass architecture that is the panopticon. I use the image of glass as a metaphor for digital technology. The project contains its own critique. It criticizes its own medium. I understand the criticism of the medium because I was the first to make it.

Glass house, 2024

GS: It wasn’t a question of criticism on my part, but simply a desire to discuss the question of stages. Writing begins as painting. Painting creates writing through simplification and trivialization. With writing, you can obtain literature, which is something other than painting. But it produces emotions. You no longer feel the primitive effort of painting, of the manufactured, but the mechanical and automated dimension. It’s a step that can lead to something else.

BL: I continue to develop “traditional” projects, but these have a limit, that of my hand and my graphic skills. In the virtual reality project, Ito Meikyū, I’ve pushed back that limit. It’s all done with the help of the computer, a technique that is no longer new. I only used artificial intelligence for Glass house, and haven’t touched it for a year and a half now. You can create very ordinary images with these tools, but if a designer adds thought and even his or her own personal techniques, it becomes an additional tool. You could create a drawing, ask artificial intelligence to make a version of it and then redraw it. You can play with artificial intelligence the way you used to play with photomontage. It’s just that the tool is different, it can automate and create infinite variations. Glass house was my first radical and somewhat provocative attempt, in which I mixed my work as an animator. There are parts that are completely animated by me, others that are completely animated by the A.I., and others that are half and half. It’s hard to tell which. I find this ambiguity interesting.

Glass house, 2024

ÉN: It’s paradoxical to find chaos with digital technology in the sense that fundamentally the tool is not random, even when you use the random commands of a program, it is not inherently random. We can much more closely compare automatic drawing to randomness, which would be – in quotation marks – “chaos”.

BL: If I put water on a piece of paper and then ink, it will never do the same thing, it’s the experimentation of chaos live. In a film, we don’t necessarily perceive it unless a voiceover evokes chaos. In a way, there are thousands of ink stains in the film, thousands of chaoses placed one after the other. Except that’s not what we appreciate in the film project because the lines and shapes are very controlled. Even if we can do this experimentation of chaos every day, when I make a film, there is a desire for control, as for the walk of a character where we force the material to produce a defined form and, in this constraint, we lose this fundamental aspect of the material.

ÉN: In Stan Brakhage’s films, we are entirely in the task and, suddenly, the image seems chaotic.

Dog star man by Stan Brakhage, 1961-64

BL: Yes. I am more of a filmmaker of control, like a watchmaker who creates small machines that I am always very happy to make. But I also have this frustration of telling myself that deep down I am just a mechanic. This machinery is at the service of a subject, it releases a form of poetry. Beyond the mechanics and the optical dimension, we are as spectators touched, jostled. The ambiguity of the images also produces these emotions. In Ito Meikyū, some spectators find a scene funny, others find the same scene embarrassing and others, sad. I like that. I propose multiverse, multifaceted projects. Obviously each viewer makes the film, it is the viewer who makes the work, as Marcel Duchamp said.

Ito Meikyū, preparatory drawing

ÉN: In terms of writing, at what point do you decide the length of the film? For example, for Rhizome, at what point do you decide that the camera stops zooming out?

BL: When I was developing Rhizome, I thought it would last 10 minutes. In the end, it lasts 12. I thought that La chute would last 12 minutes, it lasts 14 minutes. This difference comes from feeling, from feeling. Finding the ideal timing for a film is not something I can write or storyboard. I have to do it to know. Music helps sometimes. I once asked the composer Daniele Ghisi to do an improvisation for the beginning of La chute and that allowed me to set the timing.

We also give ourselves constraints. Rhizome, which is a bit minimal, lasts 12 minutes, would 20 minutes have been better? I don’t think so. As I work a lot on cycles, time is not given, it is to be chosen. I am not constrained by the animatic or by the number of drawings per second that I have to do. I still have a space of freedom, namely that of the camera, of the filming time. And that is rare in animation. For each project, I do not know how many drawings I am going to do and I sometimes do not know how many shots I am going to do either. I work more in terms of strength than in a logic where we fill the boxes of an animatic. I cannot cut into timings. I often use the image of the sailboat, that is to say that depending on the size of my sail and the wind, I arrive at the place where I want and sometimes I stop earlier, sometimes I go further than expected, depending on the means: more money, less money, more team, less team, and depending on my personal energy too.

Rhizome, 2015

ÉN: Do you delegate a lot of animation? Or some of it? How do you manage that, since you are in this constant process of having to gauge, for example, the duration of a loop before it disappears.

WH: We can see the collaborators mentioned in the credits, like Capucine Latrasse for example.

BL: When I was a student, I obviously did everything by myself. I did everything: I was both an animator, an author for the writing and graphic research, a technician for the compositing, with the exception of the sound. Starting with Rhizome, I started working in a team and delegating. I had an animator and sometimes someone for the hand inking disconnected from the animation. In Rhizome, it is inked and animated at the same time. In La chute, it is animated with lines and then inked separately by students to whom I give a standard inking since these are repetitive tasks that do not require a huge amount of expertise, it is just a one-week apprenticeship for a designer.

I also like working with animators who have their own style and their own strength. I am not a very good acting animator, my specialty is rather the fluidity of animations, certain special effects like animating plants, buildings or even characters but as constructions rather than in situations. Capucine Latrasse animated certain situations in a more subtle way than I would have done.

Ito Meikyū, line test by Capucine Latrasse & Agathe Sollier

My research on timing is different since often animators work on key poses while I design “straight” animations. Not having the same style allows to vary the animation styles in the same project. I try not to always impose my style but rather to use the strength of their proposal to create a greater variety in the project. In Ito Meikyū, there is a lot of 3D and programming.

Ito Meikyū, line test by Ryo Orikasa

GS: This may be secondary, but what type of tool do you use? Unity, After Effect, artificial intelligence…

BL: For a drawing project, we animate on paper on a light table, unless it is an animator who prefers drawing on a tablet, but the final inking is done on paper. We digitize the sequences, process them on Photoshop and composite them on After Effect. For Ito Meikyū, the modeling and placement were done in Blender. Everything – 2D animations, 3D animations, modeling, programming and sound – is assembled in Unity.

Ito Meikyū, 2024

In Glass House, artificial intelligence was used in some sections, I experimented and wrote prompts in Stable Diffusion and it generated an avalanche of images of which I used about 30% in an editing logic. Using a simple prompt generated disappointing images. I instead created animations that I sent to the program and asked it to modify them. I also fed the program with videos that I had not made, like Metropolis by Fritz Lang and found footage that I modified with artificial intelligence. Parts were completely made on Blender. I sometimes used images generated by artificial intelligence, which I isolate and recompose. These images become textures that I reanimate in Blender.

WH: I come back to the themes. We talked about solitude. The characters or particles work on themselves, in their own loop, and are caught in a larger play of patterns, the characters form a crowd. This creates a tension between characters who are folded into their cycle of movement and the fact of making a mass by constituting a whole, by becoming the graphic pattern of a tapestry, to which is added a game of compositing that makes it superimpose and remix. So if solitude constitutes a theme, the psychology of crowds, which was conceptualized at the end of the 19th century, also comes into play.

Kyrielle, 2011

BL: I haven’t done much research on crowd psychology. But mass effects are important in my work. It comes from my taste for Hieronymus Bosch. We are always between the isolated cell and the whole. Each isolated cell exists by itself and with its own strength but it exists at the same time in a whole, like, for example, in Rhizome, a landscape or, in The Fall, a parade. In Ito Meikyū, we could talk about an encyclopedia or the idea of a collection and the relationship of the elements between them in the collection. It allows the elements to react together in the manner of a chemist. It’s collage. They could have been separated but they are together, and they create a group and, from the group, they create another group, then a supergroup.

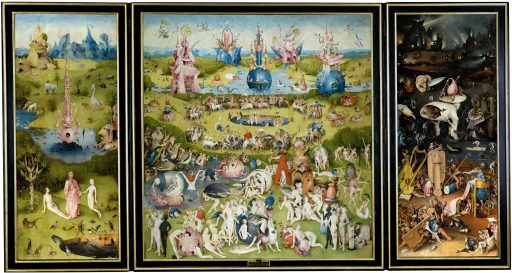

Le jardin des délices (triptych) by Jérôme Bosch, 1503-1504

Z: Is it possible to identify patterns in Stan Brakhage’s films or is it the viewer who projects an order into this chaos?

BL: He works on the film itself and the film itself is a binding, hyper-structuring structure.

ÉN: The sensation of chaos is located in the viewer because the approach is very structured on his part as we can read in Metaphors on Vision, where we understand what brought him there with a very logical and not at all chaotic train of thought.

Metaphors on vision by Stan Brakhage, 1960

VG: Chaos is a question of scale. If you look at the particles, they seem very chaotic, if you step back you see a homogeneous cloud.

I personally compare Boris’ work to Johann Sebastian Bach’s Goldberg Variations from a mechanical perspective – besides, you defined yourself as a watchmaker. I just wondered if you didn’t miss not being able to say something rather than proposing a mechanism of which you are the generator? In his masses, Bach allows himself a lot of improvisation, there was then a more emotional side, which rarely shows through in your films, except perhaps in Ils tournent en rond, which is humorous. I have the impression that you rarely take a position on the world and that you present us with a universe where we are perhaps intellectually fascinated, but the creator that you are disappears.

BL: Yes. This is not true for all projects. Even in La chute, there are things that are said, that are personal, that are the fear of disappearance, there is an ecological dimension.

My latest project, Ito Meikyū, is more emotional and personal, with the idea of birth in particular, with the fear of losing a child. It is true that I am not a storyteller except for my daughters. It is not very present in my cinematographic project but I am nevertheless interested in cinema, in narrations and in literature. I tried not so long ago to create a more narrative scenario but I have difficulty doing it and structuring my stories.

But each project brings particular emotions if we see them on a cinema screen rather than on a computer screen. They may not talk about me but they talk about a condition of humanity. It is distant but it is not totally disconnected. It is not totally formalist. We can criticize formalism and, sometimes in contemporary art, we don’t like certain things because we don’t understand, we have to decipher, go read the label to understand the artist’s approach. I am in an intermediate approach where we don’t need to read the short text to understand the works and we can let ourselves go. Francis Bacon doesn’t explain his ambiguous figures in metamorphosis, but it speaks to us and allows us to project ourselves into his stories. For La chute, some spectators said that it talks about illness, others, about the disappearance of the plant world. We can project a lot of things, I like this idea of multi-narrativity.

Ito Meikyū, 2024