THEORY

MASTERCLASS

WRITING ANIMATION : ANDREA MARTIGNONi

Zepe: Do you often do workshops?

Andrea Martignoni: I really enjoy working with animation students, not sound students, because obviously they might be more competent than I am.

In animation, it can be interesting to propose a different way of conceiving sound. But it only lasts 3 to 5 days maximum.

Georges Sifianos: To start with a general question, how does your work fit in with the making of the films: are you contacted at the conception of a project, even before the images exist, or do you intervene afterwards, on existing images? Of course it can be different from one film to another…

AM: It depends on the project. Some ask me to start working with animatics. It’s something I don’t really like to do because it’s better to work on the rhythm and on the editing that’s already been finalised because you don’t have to redo the synchronisation, and because for me the technique that’s going to be used is going to give me a lot of ideas. There have been several occasions when I’ve worked on an almost finished film and sometimes on the final cut. But sometimes I’ve started the soundtrack before the film, from sound to animation, because I’ve had a proposal that really moved me, and that changed my point of view on sound in animation.

Fino by Blu (2009)

It happened to me when I first worked with Blu. It wasn’t a film he made on walls. The film was called Fino. When we first got to know each other, he asked me to do 2.5 minutes of soundtrack without knowing anything about the film, and he himself knew nothing about the film. It was a kind of sound and visual improvisation. So I did 2.5 minutes with sounds I had in my computer, trying to create a narrative soundtrack in the sense that there was a progression, but without knowing the story. Blu made the film from this soundtrack. It wasn’t music but sound effects. In my opinion, this film is extraordinary, a very small but very beautiful film. And I found it very interesting, it touched me a lot in relation to the workshops on sound in animation with children, with professionals or animation students: starting with sound to get to animation. It leads to a faster process, especially with children, based on rhythms and reference sounds.

GS: There can be several approaches to music: a simple accompaniment, a real dialogue between the music and the film, or when the music takes the initiative and guides the film… We saw 7 films before this meeting. Can we talk more concretely about the collaborations with their directors? For example, how did you work on Roberto Catani’s La Testa tra le Nuvole , or did the voice already exist in Andrey Zhidkov’s Happiness?

AM: Sometimes I’m offered films that have already been completed. If I like it, I talk to the director and try to understand whether he has a specific idea for the film or whether he lets me do what I want, as has happened sometimes, with absolute freedom. Then we talk about the result and the changes he’s obviously going to suggest.

On the question of composition and music, I don’t consider myself to be a musician or a composer of, in inverted commas, ‘classical’ music. I can’t compose for a quartet or an orchestra. I like to be responsible for the sound of the film. It depends on the film project. I can do an electro-acoustic composition that sometimes uses small musical instruments or I can ask musicians to do certain things. But I use a lot of field recordings: noise, sounds made with objects and sound effects. What I like doing most is a mixture of all these things. Happiness, or the three collaborations with Blu are good examples of what I’d always like to do when I’m doing the soundtrack for a film.

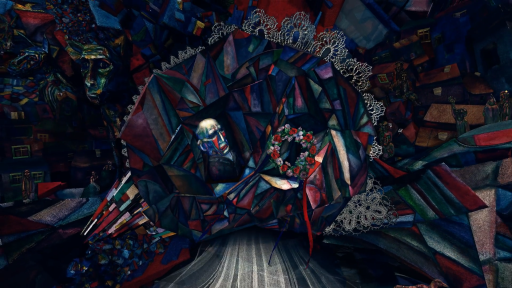

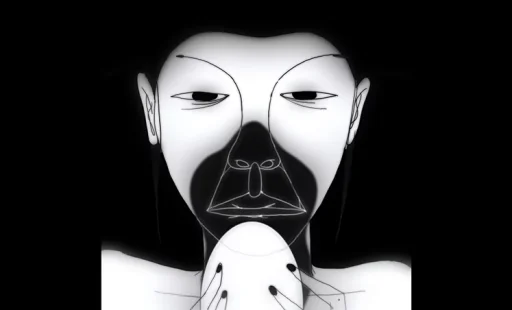

Happiness by Andrey Zhidkov (2020)

For Happiness, Andrey Zhidkov asked me to work on the film at the last minute. He had almost finished the film and the voice had already been recorded. I don’t take care of the mixing, I go to a mixer or one suggested by the production, with whom I work in studio. In this case, if the money wasn’t there, Andrey worked with a friend. It wasn’t easy, it was just before the war in Ukraine. I worked for free on this film, because I really liked it. The beginning of the film had to be quite strong. The film is quite eclectic in visual terms, it’s quite interesting. At the time I couldn’t go back to Italy because I live in Berlin. It wasn’t easy to travel at that time. I asked my brother, who is also a musician – he builds and transforms instruments. He took apart an upright piano, with all the strings, which he could put on the floor and move around on. I asked him to do a kind of improvisation on the piano and to use a hammer on the strings to get a fairly loud sound, which suited the character on this iron bed in this strange universe with pieces of colour that are constantly moving.

Happiness by Andrey Zhidkov (2020)

My brother sent me about forty minutes of improvisation. I chose and edited the passages I liked. There was a sort of strange wedding and I used a chime that I made myself out of cardboard with holes in it and a pencil to play the score of a piece of wedding music [Editor’s note: Mendelssohn’s Wedding March] that I used in reverse.

Happiness by Andrey Zhidkov (2020)

With Roberto Catani, it was a different approach because he invited me to work on the film La Testa tra le Nuvole, Absent minded, which for me is one of the best films I’ve ever worked on. He sent me some drawings with a very precise film script and sound ideas. Because most of the scenes came from memories of sounds he knew as a child.

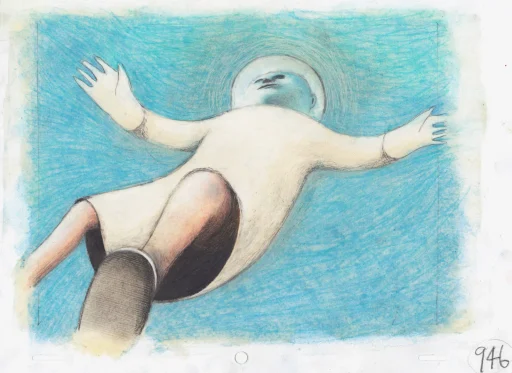

La Testa tra le Nuvole by Roberto Catani (2013)

It’s a biographical film about the problems he had when he was in the first year of primary school and which came back to haunt him. It’s a bit exaggerated in the film. Certain sounds were very precise: the sounds of the school, the bench falling, the chair falling, the purse on the floor, the shoes, the coat hook. I had to edit these sounds precisely and in the right places.

La Testa tra le Nuvole by Roberto Catani (2013)

Then there were parts where the child escapes into his head because he doesn’t want to stay in reality. I was then free to do what I wanted, but with references: he wanted brass band music and children’s voices singing the same piece as the brass band. It wasn’t an easy challenge for me, but I found the solution because I used to be part of a very politically committed brass band in Bologna called Banda Roncati. I wasn’t a member at the time but I still knew them well.

Banda Roncati

La Testa tra le Nuvole by Roberto Catani (2013)

At the time, they were playing in a place that wasn’t in the open air, so I was able to record the brass band with, let’s say, average quality, but the sound quality wasn’t important anyway. And the girls in the brass band were singing. I took that and changed the pitch a bit by two or three semitones upwards and it really sounded like it was being sung by children. Then I recorded the same song with the same brass band but in octet, with just the wind instruments, trumpet, sax and so on. I was really happy to find this solution, which combines ingenuity and luck, otherwise I would have had to go and find a brass band in a small village.

La Testa tra le Nuvole by Roberto Catani (2013)

The most important part of the film, in my opinion, shows rather abstract images representing the child’s dismay when confronted by the schoolmaster, and then we hear the terrible sound of chalk on a blackboard. Roberto asked me to exaggerate it. But the image doesn’t show anything, it’s the sound that makes the story, namely the passage between the child’s uneasy situation and the moment when he gets out, represented by the child’s fall into the water.

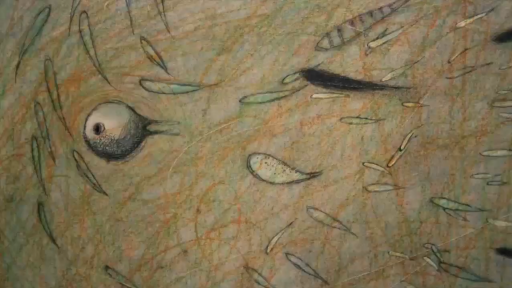

William Henne: In La Testa tra le Nuvole, the sound actually fills in moments when the image is extremely stylised, when the sets fade into the background, and it’s clear that the sound was thought out by Roberto Catani from the outset. Sometimes the sound even makes metaphors explicit: for example, at one point we see a shoal of fish, but what we hear are schoolchildren shouting. To what extent did Roberto Catani already have this in mind? Was this metaphor of sound written into the script?

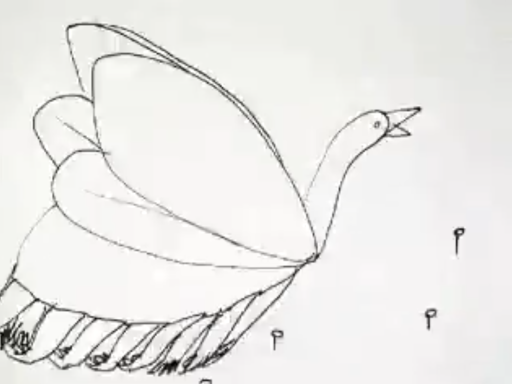

AM: Yes. The way the fish move is really like little children running and shouting in the school playground. The metaphor is obvious. He had already written that very precisely. There were times when I was free to do whatever I wanted at the beginning. Like after the scene where the child falls into the water, there’s a not very happy scene with a dead bird and I used a bird call that gave a kind of tired breathing and it was quite beautiful.

La Testa tra le Nuvole by Roberto Catani (2013)

Z: When you’re working on a film that’s not very far advanced, do you follow a method where you assemble elements side by side or do you already have a fairly precise schedule? Before you even start capturing, transforming or editing sounds, do you already have a score in your head?

AM: I’m not really comfortable with putting very schematic and formalised elements down on paper. I’ve worked on animatics before. But it’s not what I prefer. Animatics don’t inspire me, because I don’t see the finished film. It’s the film itself that inspires me, that gives me ideas for creative things to do. With Roberto, it was very easy because it was written. There was no animation, but there were the drawings. I could go to his house, which I did, and I could follow his drawing technique, which is very complicated, very long and very slow. He works alone, except for the editing. I could see the animator’s work and feel that I was already in the film without seeing the finished film.

Roberto Catani

It doesn’t happen very often because of the distance and the fact that we’re not in contact. I’ve worked three times with Izabela Plucińska who lives in Berlin and we can see each other and meet for 3 hours. It’s not a problem. I love meeting people but it’s not always possible.

Evening by Izabela Plucińska (2016)

GS: How did the improvisation with Pierre Hébert go? As far as I can tell, Pierre Hébert had an overall concept and developed a particular system for creating images, but how did you, as a musician, fit in with that? Was there a body of prepared sounds? Were you familiar with Pierre Hébert’s work and did you think that these types of sound would work with his way of doing things? Did you discuss this beforehand?

Pierre Hébert

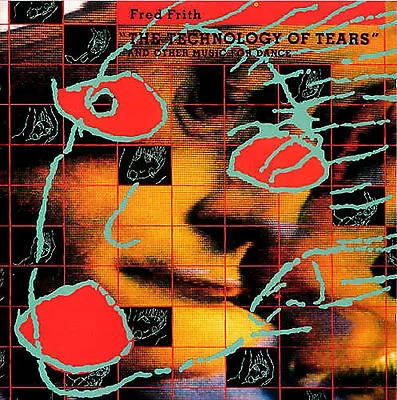

AM: It’s simple and complex at the same time. After my master’s thesis at university on the work of Normand Roger, on experimental cinema in general and animation, and in relation to sound. But the specific work consisted of analysing certain films for which Normand Roger had created the soundtrack. I won a research grant from the Canadian government to spend a year in Montreal, at La Cinémathèque Québécoise and the NFB [National Film Board] film archives. I wanted to make more contacts: Pierre Hébert among others, Arthur Lipsett who interested me a lot, Norman McLaren who I wanted to learn more about. Pierre Hébert is a reference because one of the favourite vinyls in my collection was Fred Firth’s Technology of tears for which Pierre Hébert had designed the cover. Technology of tears is the name of a performance, accompanied by dance, that Fred Fritz played with Pierre, who did the set design with live engraving, as if Pierre Hébert were one of the musicians.

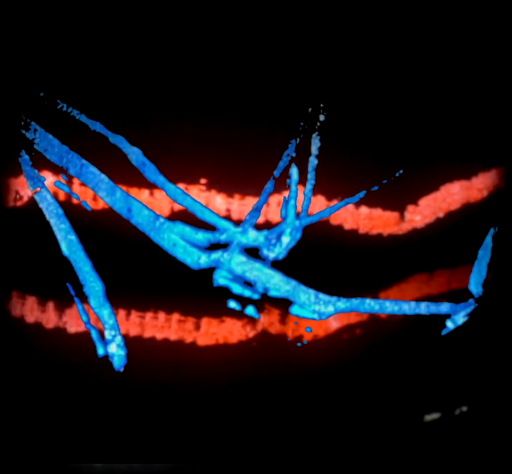

Technology of tears by Fred Firth (1988)

It was a challenge to work with Quebec musicians Jean Derome, René Lussier and Robert Marcel Lepage. He showed a film that had already been made and the musicians improvised on the film, Chants et Danses du monde inanimé – Le Métro, and the final soundtrack is a montage of the best live performances on the film. Jean Derome said to Pierre: but you’re at ease, you’re putting on your film and we’re getting wet on stage to do the improv, you should do what we’re doing. Pierre loves a challenge and is very intelligent. He started to think of a way of working like a musician, to make a live film and he invented this system of loops of about 40 seconds of film that pass through the projector, giving him time, for a few seconds, to burn certain photograms into the film. It’s incredible to watch! He gave me copies of the VHS cassettes of all the performances he’d done with Bob Ostertag, Robert Marcel Lepage and Fred Firth, which I’ve kept in my archives in Bologna. My dream was to work with him. We worked together for the first time in Milan. Knowing that he works with loops that constantly modify the content, I obviously worked with loops of instrument sound that were played a bit randomly, without much preparation.

Pierre Hébert and Andrea Martignoni at Area Sismica, Medola.

We continued to work together, depending on the occasion. There was a performance in a contemporary music club, Area Sismica, not far from Bologna, near Forli. I had different instruments. He recorded the performance and chose a piece of the music and put it in the film Rivière au tonnerre, which was made in a way other than live engraving on film, which is just as complicated as working with images. He took the music from the live performance where he was burning the film and put it on this other film.

Rivière au Tonnerre by Pierre Hébert (2011)

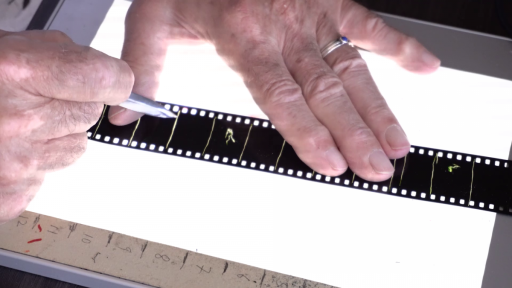

Later, he was invited to Glasgow, to the school where McLaren had studied, to give a performance to mark the centenary of McLaren’s birth. He asked me to play with him. I thought I should do something similar to what he was doing. So I thought I’d do some engraving on the sound part of the 16mm film and put it on a loop. I was preparing the live performance by adding guitar effects and doing the performance his way. Our loops were of different lengths, mine could be 35 seconds long while his was 40, it didn’t matter. But as we went along, there were accidental synchronisation effects. It was very interesting and the further we went, the more complex the visuals became – the soundtrack was somewhat limited by the sound you can get by burning film – in a pretty incredible crescendo.

Our best performance was at the Louvre in Paris.

Scratch by Pierre Hebert & Andrea Martignoni (performance au Louvre, 2018)

Pierre now has health problems and can’t travel. We met a lot in Annecy but his situation now really makes me think that it won’t be possible to play together again.

Ethann Néon: Did you have two different films or were you both shooting at the same time on the same film?

AM: No, that’s impossible. We didn’t have the same piece of film but it was the same type of 16mm film. We could have, but it would have been a total mess.

Digital Scratch by Pierre Hebert & Andrea Martignoni (Poznan, Pologne, 2012)

EN: You used the projector to emit only sound?

AM: Yes, the projection lamp wasn’t lit and I only had the lamp that read the sound track, by optical reading. You could hear the sound of two projectors at the same time in two different parts of the auditorium. And when we played in Paris, Pierre used two projectors at the same time.

GS: Norman McLaren used a series of small lines of different frequencies for each note. A high-pitched note might have twenty or thirty lines, a low-pitched note far fewer (unless it was the other way round…).

AM: It’s an operation that can only be done in the studio, not live. Pierre photographed the sound part of the film with the cards he had prepared and, once the lab had developed the film, we could hear the result. It was more complicated.

GS: My question was in another direction: how did you manage time? Because drawing by scratching, the way Pierre Hébert sketched his images, takes less time than drawing little lines to get a note. How did you synchronise the two?

AM: We didn’t synchronise because synchronisation was a matter of chance. I could make sound from what I saw without it being very precise, but my scratching couldn’t compare with Pierre’s drawings, which were very precise on such a small surface and could be recognised as shapes. For my part, a large scratch generated a much louder noise and very small scratches superimposed on each other generated a rather high frequency, so I had relative control over the frequencies, but not very precise, and over the intensity of the sound. As well as the rhythm, of course, but it all depended on chance. Sometimes I’d listen beforehand to modify the sound and throw in loops and create sound effects, adding reverb or distortion. We really liked this element of chance in the performance.

Z: Which collaboration did you consider the freest?

AM: The one with Blu and the one with Pierre, who have really had a big impact on my life, because there’s a thought behind it. It’s not just a film that you’re going to soundtrack. They’re both a bit of anarchists in a way and very politically committed.

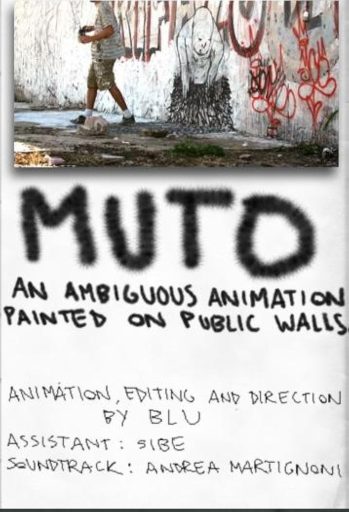

With Blu, it was incredible because we started working together with an idea of his, namely to start with sound, which was an interesting challenge and one that I take up in workshops, such as those with students in Bucharest. He really gave me complete freedom on his two films, Muto and Big bang big boom. It was a challenge, I wasn’t sure I could do a good job, I didn’t want to ruin the film because you know if the soundtrack is badly done, it can harm a film or enhance an average film. They say that music and sound make up 50% of the quality of an animated film. I’m not sure, but it can happen, because animation starts from a blank sheet of paper and sound starts from silence, from which anything is possible.

Muto by Blu (2008)

With the freedom Blu gave me, my approach was a kind of mickeymousing with all the sounds we could find, following the rhythm and quality of certain images. I already had a good knowledge of animation at the time and I’d never seen anything like it. Because Muto was really a very frightening object for the animation world. So I thought I’d illustrate it with strange sounds and a surreal aspect, in the same way that it’s surreal to see images moving on city walls. Blu’s first idea was to ask several people to do several soundtracks. As soon as Blu finished the film, he put it on Vimeo and YouTube, something we don’t usually do in the world of animated films, to comply with certain rules such as festival screening. But the film was so important that all the festivals selected it. I was in charge of distribution for Muto, even though the film was online with millions of views. Even the National Film Board wondered if it could change the rules of distribution because obviously it had broken the rules. This spirit really touched me because it showed how art can change established rules. Because if art proposes something new, who cares about the rules?

WH: There’s a clear parallel between this kind of wild distribution, which ignores the rules of festival distribution, and street art, which is about something very immediate and clandestine.

I wanted to take a very concrete example from Big bang big boom: at a given moment, an animal is transformed. At first, it’s a mouse, evoked by a kind of rubbing on plastic, which sounds a bit like a mouse squeaking. Then the same rubbing is used when the mouse transforms into an elephant whose paws give the impression, in terms of sound, that they are crushing a plastic toy. Then the elephant turns into an armadillo that rolls up and down like a balloon, and here the sound is a kind of percussion on glass. The sound effects both accompany the image and at the same time bring in other connotations because they are not at the first level. We vacillate between a form of first degree and a game of distancing. I imagine it was all created instinctively.

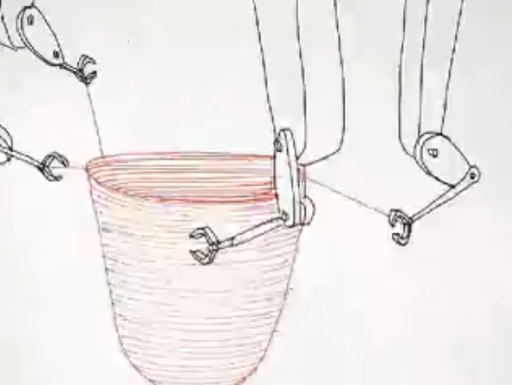

Big bang big boom by Blu (2011)

AM: As I went along, I kept finding new things. In this case, where the mouse becomes an armadillo, I beat a pack of cards and when it becomes a sphere, it’s a marble spinning in a glass dish. I tried several things. When the shark eats a small fish that swims in the cement of an abandoned street, I was a bit stuck and sometimes chance makes things right. I was living on the first floor in the centre of Bologna. There was some work going on. The whole street was being redone. I was preparing Big Bang Big Boom. I had to stop because I was recording the sound effects at home and I thought I’d take advantage of this forced stop to record the work with the jackhammers from the first floor window, which is an interesting point of view in terms of sound. The workers won’t notice that I’m recording them. I put together this sound that has nothing to do with a shark eating a fish, but it does have to do with the street in which these drawings are evolving. And it fitted perfectly. I was amazed myself at what I’d come up with.

There are others: we often met up on Thursdays to play table football with Blu and Gianluigi Toccafondo. It was the crème de la crème of the Italian entertainment scene. I said I was going to record them while they played. They were very good players and the games were fast. In Big bang big boom, Blu painted on the walls of an abandoned school, the blue paint runs up the walls of the school and you see dice rolling. I put in the foosball sounds of Toccafondo and Blu and it comes back to me every time I watch the films.

Big bang big boom by Blu (2011)

WH: Then, as with any film, there’s the work of sound effects before mixing, reverb depending on the environment depicted in the film, or more muffled sounds.

AM: For Big bang big boom, I did everything at home in stereo, it’s not 5.1. It has effects. I’m not a composer, I’m not a musician, I’m not a technician, but I try to put things together.

It wasn’t possible to do a professional mix for Big Bang Big Boom but I still won the prize in Dresden.

WH: That means that there wasn’t necessarily any use of sound filters in the sound editing to give more echo, reverberation or muffled sounds.

AM: Yes, but in a very basic way.

GS: You said that a sound can resemble an image. How can a sound resemble an image? Can we refine this notion of the image/sound relationship? What are the similarities between image and sound?

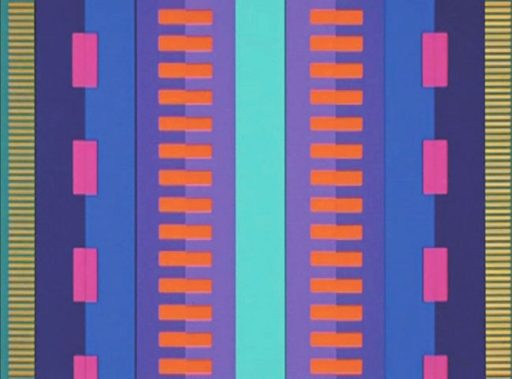

AM: It’s more theoretical than practical. There are no rules. For example, McLaren’s Synchromy is an extraordinary film from a theoretical point of view, but from an aesthetic point of view, it’s not the best. When there is coherence between the form of the images and the sound, it doesn’t always work well.

Synchromie de McLaren (1971)

So translating an image into sound is obviously not the best thing you can do. Usually it’s different things that work best together. I don’t think there are any rules, just special cases. You have to ask yourself each time what sound best represents this image. But it’s not a clear-cut translation of an image. What is a fish eating another fish? Is it water gurgling or roadworks? There are no rules, because when there are rules, things become flat.

The example of Synchromy is interesting: it’s not very beautiful if you compare it to Blinkity Blank. These are camera sounds that work with engraved images, one photogram in four. So how do you make the connection? You won’t find a better soundtrack for Blinkity blank than the one Maurice Blackburn made for this film.

Blinkity blank de McLaren (1955)

GS: If you have to assign a sound to an image, what happens? There’s chance, as we said. But at what point are we going to say to ourselves: ‘OK! I found that sound there by chance. Does it fit? Or does it not?’ What is this ‘glue’?

AM: It’s a question of perception that doesn’t follow any precise rules. Sometimes if the director of the soundtrack thinks that the sound fits well with the image and the director of the film agrees, then the audience will probably perceive it as such. Because obviously the master of the film remains the film director, helped by the soundtrack creator.

I have a slightly different approach. For the last workshop that I did at Anim’est [Bucharest] a few days ago and that I’m also going to do at Animateka [Ljubljana] just before the festival, we’re recording sounds with the animators. You can find sounds everywhere, including in the room where you’re working: a computer mouse or keyboard, a pen, etc. We create sounds in all sorts of ways. We create sounds in all sorts of ways, choosing the ones we like and recording them in the best possible way with a recorder, which gives us little sound sequences of 2-3 or 5 seconds on which they’ll create an animation. And I usually ask: ‘Please try to move away from the sound source. We’re not going to show water if there’s water in the sound’. I get good results. This leads the animator to always think about the importance of the soundtrack and the sound. You can start with sound, not just music. Everyone has seen Allegro non troppo [Bruno Bozzetto, 1976], Fantasia [10 directors, 1940] and A Night on Bald Mountain [Alexandre Alexeieff and Claire Parker, 1933], there are many examples of extraordinary films. But starting with an abstract sound, which is not linked to music, which is not necessarily beautiful, which is noise, whether random or not, means that you can create different images for each sound. You can make a dramatic or comic, ironic or literal translation. I’d love to take the time to do this, but it takes at least a day to find a sound, record it and create a little animation. I’ve done this in St Petersburg, China and Italy, sometimes with incredible results.

Allegro non troppo de Bruno Bozzetto (1976)

Z: When we work on the sound for films, we generally work in layers. When it comes to mixing, we often feel that there’s a sound void between these layers. The sounds, whether they are sound effects or sonoplasties, then become very isolated, with no element linking them thanks to the work on different types of silence. In the films Andrea Martignoni works on, this impression of emptiness does not emerge; the silent atmosphere between the concrete sounds constitutes an additional dimension, with its own identity.

How do you talk about silence? It’s generally difficult to talk about silence in films…

AM: When I think of silence, I obviously think of John Cage, which is perhaps not very original. He said that there is no such thing as silence, except perhaps in the vacuum of space. He once experimented with an anechoic chamber where there is almost absolute silence because all noise is absorbed by mattresses all around the chamber. He began to hear the sounds of his own heart. When there’s silence in a film, there’s always sound coming from the room you’re in. It creates a gap. Usually we reproduce the reality where there is never silence and put in frequencies that we can’t hear very well but that are there, like the sound of electricity, a fridge or a background sound, to avoid absolute silence which would otherwise be a little strange. It’s an absence of sound but not silence, it seems to be the same thing but it’s not.

GS: Earlier you mentioned the term mickeymousing, which means putting sound on all the time. And indeed there is silence as a discreet sound as, for example, in Memorie di Alba [Andrea Martignoni & Maria Steinmetz, 2019], with this lady’s singing voice, there is a background, something that brings the scenes together. Can you talk about this polarity between mickeymousing that saturates the sound and sonic discretion?

Memorie di Alba d’Andrea Martignoni & Maria Seinmetz (2019)

AM: Mickeymousing saturates the sound but, in the negative sense, it’s used for live-action films because the criticism is that we’re going to follow the character’s every move. But when you think of Scott Bradley and the sound engineers who did the soundtracks for the big films at Metro-Goldwyn-Meyer in the 50s, i.e. Chuck Jones and Tex Avery, it’s an essential reference for the music and sound of animated films because it’s incredibly inventive. I tried to do that with Big bang big boom without imagining that I could get the extraordinary results that Carl Starling and others were getting with an orchestra used as a palette of sounds to produce mickeymousing.

In the case of Memorie di Alba, I started with the idea of recording my mother and making a kind of animated documentary because one day, with Muto, we were selected to go to Doc Leipzig where Annegret Richter and others around Anidox were present. In 2008, there were already a lot of animated documentaries, but it’s become fashionable now. There were interviews with people who had been imprisoned and always very committed stories, with very powerful testimonies. I thought that history is also made by ordinary people and I thought of recording the voice of a normal person like my mother, who was already 85 at the time. She had a long love affair with my father, which was rather strange in a way. I also asked her to tell me stories about the 2nd World War because she was already 12-13 when the war started. In the end, the most touching story was the one about my father. So I recorded it, edited the recordings and then I had the opportunity to make the film with my partner at the time. She made the film, adding her own ideas, but the structure of the film was determined by the recording of my mother’s voice and by her memories. I tried to distance myself from this and only include the elements necessary to tell his story, to relate different moments, to make the link between them, not to leave too many silences, in the sense that there were pauses in his speech and in the sense that it was a question of accompanying the images.

Memorie di Alba d’Andrea Martignoni & Maria Seinmetz (2019)

GS: I find that the background sound is more discreet. In other films, the background music is more present, in Blu’s films for example.

AM: We could have done the opposite because in Blu’s films the image is so strong. When I saw Muto for the first time, when Blu came back from Argentina with the film cut, I said to myself: ‘Well, what should I do? Muto means mutation, but Muto in Italian also means mute, that which cannot be heard, that which cannot speak’. And I thought we could leave the film silent because the image says so many things that we can’t accompany it with sound. If you put sound on, you’re going to accentuate that. So I decided to push that, to use as much sound as possible, to follow the images. Someone said to me: ‘You could have used realistic sound linked to the place where Blu made the film’ in the sense that you could hear the sounds of the city. There are a few places where I put in the sound of traffic. But I found it a bit flat in the sense that when you want to know you’re in the city, the images are explicit in that they are real walls in the city on which an artist has drawn. I didn’t think it was very interesting to take a naturalistic approach to sound. That’s my opinion, of course.

Muto de Blu (2008)

Whereas, in an intimate film like Memorie di Alba, with my mother’s memories, it wasn’t just any old thing – and my daughter is called Alba – there’s a form of filial respect in leaving all the necessary space for her voice and her story, which is the most important aspect.

In Happiness [by Andrey Zhidkov, 2020] and in Postindustrial by Boris Pramatarov [2015], these are soundtracks that I love but it’s a poetic text, it’s something else, like a third level: there’s the level of writing and reading a text that is also described by the images but sometimes the images don’t describe the text being said. And the third level is the music or sounds I’ve added. It doesn’t fit with the text. Gradually the inspiration comes from the images and the images are inspired by the text even if they are not necessarily linked to the meaning of the text and the meaning of the sounds. There are only three levels. In the case of Memorie di Alba, you had to understand the story and you couldn’t obliterate the sound of the voice to understand what my mother was saying.

Postindustrial de Boris Pramatarov (2015)

WH: In Postindustrial by Boris Pramatarov, there is a lot of sound: squeaks, rubbing, clicking and above all percussion that underlines the movements in the image. The text is quite strange, and the image, which is sometimes at odds with the text, is itself strange. And the sound reinforces this strangeness. All these dimensions reinforce each other.

AM: He is a great artist and this is the first animated film he has made. The text is signed by his brother, who is a poet. The text is strange and I tried to follow the rhythm of the image. It’s one of the top 3-4 films in my filmography. But I did the soundtrack in 3 days because I was working on Recycling, a big project with Paola Bristot with several animators working directly on film and I was in charge, with others, of the soundtrack. I’d completely forgotten about the Pramatarov film that Vessela Dantcheva had given me. So I said to myself: ‘Fuck off! I have to make the film in a few days’ because I had a very tight deadline. I recorded sounds with little music boxes that my brother had made and I was rehearsing with my brother’s band. It was strange because I was playing and recording at the same time and the other musicians were getting ready to play. I asked for silence but, as happens all the time with musicians, one of them kept playing an ocarina while I was recording. And integrated this ocarina into the rhythm of the film and you get the impression that it was played expressly for this scene. You can really rely on chance because it generates surprises. It seems to me that the soundtrack contributed a lot to the film, which was selected at Annecy.

Postindustrial de Boris Pramatarov (2015)

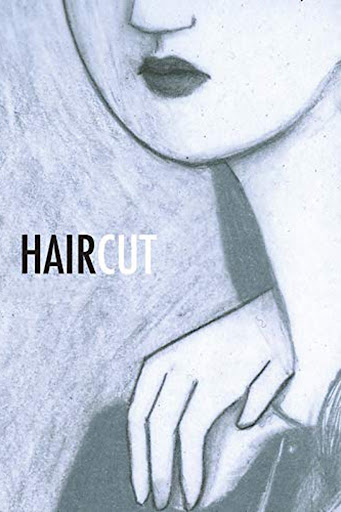

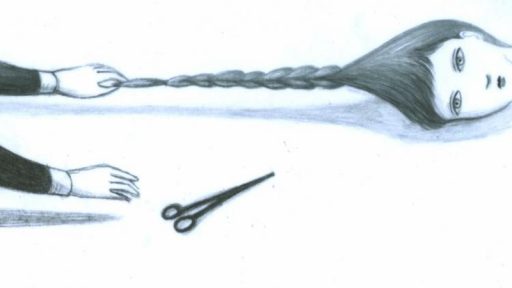

WH: We talked about the sound of chalk in Catani’s film La Testa tra le Nuvole. Virginia Mori’s Haircut is also set in a school context. We hear sounds that border on the unbearable, very high-pitched vibrations that make the film disturbing and can create unease in viewers. Both you and the director take risks.

Haircut de Virginia Mori (2014)

AM: Yes. The film is disturbing in the sense that the film’s protagonist undergoes experiences that aren’t exactly positive or pretty. You have to convey this idea, otherwise it becomes just another film.

In the case of Catani, it was suggested to me that I should remove the chalk on the blackboard sounds to allow the film to be more selected. You can never say that to a sound designer because it’s stupid – I’m not revealing the identity of the person who told me that, everyone knows him or her. It’s even more stupid to tell me this at Annecy when the film has been selected. That means that the selection committee, in particular Marcel Jean, didn’t find it that disturbing and the film won a special mention from the Annecy international jury. And then it went on to win the Animateka Grand Prize. It’s obviously a question of taste and sensitivity. I’m not too concerned about whether viewers are disturbed, the film has to disturb, otherwise it’s Disney. I’ve got nothing against Disney, but it’s something else.

Haircut de Virginia Mori (2014)

Vincent Gilot: Do you deliver all your sounds to an editor who puts them in place or do you intervene in the editing? I’m thinking of the bell in La Testa tra le Nuvole where there’s a blackout followed by the school bell. Who sets the duration of the bell? Did you set it yourself?

AM: In this specific case, I thought the black was a bit long and the bell is really long. I don’t remember it being that long at school. It was Roberto Catani’s choice to use such a long black. Sometimes I’m working on a film that doesn’t have a final cut. So I start editing the sound. At the mixing stage you can change things in agreement with the director. You can’t change the film edit, which is definitive at this stage, but you can move elements around in the sound edit.

La Testa tra le Nuvole de Roberto Catani (2013)

Sometimes I’ve done the live editing in collaboration with a colleague, Michał Krajczok, a Pole who studied sound design at Potsdam and lives in Berlin. I often work with him on the final mix. We worked together on the very beautiful film by Belgian director Soetkin Verstegen, Freeze frame, which begins with a scene similar to a Disney film. It’s a film about ice. Michał and I worked in parallel: the sound was edited and mixed at the same time in the studio. We finalised the final version with the director. I usually do everything at home, right up to the mix.

Freeze frame de Soetkin Verstegen (2020)

I’ve made two films with Soetkin, the first was Mr. Sand, one of my favourite films. She was in residence making an Anidox and she asked me to do the sound for her film.

Mr. Sand de Soetkin Verstegen (2016)

I was there to lead a workshop during the first week with students from The Animation Workshop, a workshop where, in groups of five, they had three days to make an animation from a 13-second soundtrack recording. The workshop was led by Paul Bush, who has sadly passed away.

I really enjoy working with other people. It happened to me for Martina Scarpelli’s film Egg [2018], we worked together [with Amos Cappuccio] at the Animation Workshop studio. And I’ve also worked with my brother who often collaborates but, for one or two films, we really worked together.

Egg de Martina Scarpelli (2018)

Z: If you combine sounds with images, even in a very offbeat way, it produces a third sense. For example, in Boris Pramatarov’s Postindustrial , where three layers are superimposed, or in the Beat Bit site, one of the exercises, synesthesia, shows a texture in movement created from a sound. Or create actions or objects without sound, and let people hear sounds without an image, in a different way. Or staging a word, a sound and a gesture. And sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t.

Synesthesia (beatbit.org, séquence animée par Vasco Mariano)

In Blu’s films, I have the impression that you need a hook, at least in terms of sensations: sometimes it’s a shape, sometimes a rhythm, other times a colour. If these properties manifest themselves between the image and the sound, everything else follows. In that case, a vocabulary is created, a language that is no longer just sound or image, it’s a third inseparable thing. And yet, if there isn’t a single one of these hooks, it’s very difficult for it to work. When I talk about a connection, it’s obviously cultural, it’s physical, meaning that an optical or physical process unites the whole, and contains everything else. As Andrea Martignoni says, you shouldn’t make perfect sounds for perfect images, because that’s not very interesting.

AM: You asked a question and you gave the answer.

Z: But precisely, am I right when I say that? Or are there other mechanisms that work too, without us really realising it?

AM: I completely agree with you.

I was shown a phone app called PhonoPaper, which is a camera application that lets you read images with coded sound. So someone has created sounds to translate images. It’s a game, of course. You take your phone, you scan, you scan a surface and it gives you a kind of translation, a decoding in sound, generally noises, it’s not going to make you hear a violin in front of a picture of a violin. In the end, it’s up to you to decide what sound to associate with an image. The application also lets you create your own codes by taking 10 seconds of recorded sounds and producing the image. Like anything made by artificial intelligence, you have to bring them back to your own intelligence. The app is fun, but that’s about as interesting as it gets.

GS: I know of a similar application for guiding the blind by sound: when you move towards or away from an object, a surface or a texture, it emits one frequency or another…

AM: This is a utilitarian use. I remember that in 2000, when Bologna was the capital of culture – at the time there were no mobile phones as developed as there are now – there was a route from Bologna’s central station to a centre for the blind 3-4 km away. Through the arcades and in the street, there was a magnetic line, detectable with a white cane, with a system that gave information such as the presence of a bus stop, for example. But when there were roadworks in the street, the system was interrupted and, as usual, you had to use your own ears to find out where you were.

I was very interested in the issue of the blind. I did a second master’s degree in geography and I became interested in the perception of space based on the sounds and smells that orientate blind people in the city. An empty space like the Piazza Maggiore in Bologna, for example, is a terrifying space for those born blind. You no longer have any reference points, you have no landmarks with a walking stick, you have fewer references in terms of sound. On the other hand, the city of Bologna has a lot of arcades, which are invaluable. On the other hand, the traffic is very disruptive because the soundscape becomes uniform and flat. There was a lot of sound in the past. The blind perceive the image through sound.

Piazza Maggiore à Bologne

EN: The application you were talking about simply transcribes the image into sound in the same way that film already did optically. It’s another way of translating an image into sound, whether it’s on one medium or another, in the end it’s the same thing. Of course the application is pre-coded, but so is the film.

AM: I absolutely agree with you. When I say that McLaren’s Synchromy is not his best film from an audiovisual point of view, it’s because there’s a codification: you see what you hear and you hear what you see. It’s more interesting theoretically than aesthetically.

Synchromie de McLaren (1971)

What I like about making soundtracks is to be out of code, to have no code other than the code that the film or its director is proposing at the time. The film is the director’s child, I can’t ruin his child.

EN: In another register, Guy Sherwin’s Optical Sound films play on the same principles. It’s more experimental cinema, but it could be animation. He works on film, in particular using newspaper prints that he runs live through projectors.

Optical sound films de Guy Sherwin (1971-2007)

AM: What’s great is that you can have a soundtrack recorded with the London Symphony orchestra with 100 instruments like in the films we saw up until the 80s and 90s. It was of an extraordinary level and everything was printed on a very narrow surface on the edge of the film. You can’t recreate it graphically like McLaren did, whose graphically created sounds could be compared to those of a small electronic or electric keyboard. No more than that. You can’t recreate the timbre of the different instruments very precisely. Whereas, on the other hand, this little waveform can reproduce all the quality of a symphony orchestra. It’s incredible, more incredible than digital sound. It’s the magic of cinema.

Z: Jean-Pierre Verscheure, a former professor at INSAS in Brussels and collector of film equipment, spent a week at the Portuguese Cinematheque projecting sounds and images from the last century using the projection system of the time. Most of today’s projectors that project old prints don’t have the sound or image quality of the time. The quality of cinema photos in 1920 was impressive, but the memory we have of it is distorted: we think of a less sharp, less well-lit image because of prints or copies that were not very good. A century ago, sound was incredibly pure. It’s just that today’s baffles and reproduction systems can’t reproduce it. This specialist from Mons has been collecting sound systems for decades. He wanted to offer this equipment to the city of Mons, but this was not accepted, for budget and space reasons.

Piece from the collection of Jean-Pierre Verscheure acquired by the Cinémathèque française

AM: It’s crazy, it’s like vinyl which is only a piece of hard plastic. Some people say the quality is better than CD, maybe that’s not true, but when I listen to it on headphones, the technology of the past is incredible.

WH: To take Zepe’s example from the synaesthesia exercise on Beat Bit, a viewer always makes a connection between an image and a sound, even if that sound is very arbitrary. The sound carries with it connotations and generates associations depending on the viewer’s sensitivity, in relation to his or her experience, memories, culture and knowledge. For his part, the sound designer will try to provoke sensations, with a manipulative side, as in this example of chalk on a blackboard, in a spectator (a Westerner, because obviously it won’t necessarily have the same resonance in other cultures). The Sound Designer knows what it can provoke, with his own sensitivity as a creator, in terms of connotations and associations, and some of it escapes him because the spectator himself will make other associations. To what extent can the sound designer anticipate the sensations that the film will produce?

AM: It’s mainly as a spectator that you can see what it produces.

In animation, on a visual level, in a film with, say, a realistic drawing, it’s never just a drawing on paper. With animation, your brain goes through an already very complex process to understand, unlike with live action. Sound can take you towards ‘reality’ if the sound is naturalistic. The thing I like least about sound is reproducing the steps of a walking character. If he’s wearing gym shoes, you’re not supposed to hear that step. You can see someone walking down the street and not hear anything, but in an animated film you do hear their footstep because it’s important for the narrative. And if you don’t hear that footstep, you get the impression that it’s less realistic when it should be more realistic not to hear that footstep. You don’t normally hear the footsteps of someone walking on grass or in trainers on cobblestones. And then we’ll add the music. In live action it’s less obvious in terms of direct perception. When you hear Sergio Leone with Morricone’s music, it’s a crazy amount of work, just like animation after all. It then becomes interesting to analyse the way in which music and sound can help us to understand the perception of the film and the sensations it provokes. Leone without music is great because the images are fantastic, but it doesn’t work.

VG: Is sound automatically more realistic than images? In animation, as soon as a sound can be identified, like a door slamming, we’re immediately in reality, whereas when we draw in animation, we always know that we’re outside reality, that we’re in an interpretation. Why is it that sound takes us so far back into reality, in spite of ourselves, whereas music is normally just as fabricated as a cartoon?

AM: Yes, I completely agree in the sense that animation is abstract like music. The sound serves to hold on to our experience in real life. It depends on the film. In Blu’s films, you’re free, you don’t have to feel tied to reality. There’s almost no noise or sound that’s connected to reality. It’s so surreal.

When there are more precise, narrative scenarios, we help the image to connect with reality.

VG: In Muto, there are cars going by, aren’t there?

AM: You can hear cars at the beginning when Blu filmed the passing cars frame by frame. There were no drawings, just the reality of the traffic. I wasn’t going to put a horse in it. At first you don’t realise that it’s animation. You have to wait for the drawing of the hand coming out of the bricks to realise that it’s mural animation. Another world, another dimension of reality opens up. The sound immediately joins this new dimension and leaves the reality of traffic behind.

Muto de Blu (2008)

GS: As you’re also a festival director [Editor’s note: Animaphix in Bagheria, Sicily], do you have any observations about the music that inspires you from the other films?

Animaphix

And a more down-to-earth question, how much does a piece of music cost?

AM: I can’t answer that because I don’t have a price book. I was a spectator of animated films before I started doing sound for animation. My master’s thesis dealt with sound in animation long before I started doing sound for animation. It was more of a theoretical and historical approach to sound in animation. I started doing it when I came back to Italy from Canada in ‘99, so 25 years ago.

I really like selecting films and obviously I take a look – a listen – at the sound of the films I have to choose from. Usually, good films always have a good soundtrack. A few years ago, as artistic director of the festival, I decided to award a prize for the soundtrack because I thought it was important. Not many festivals do this. For the soundtrack and not for the music, because the definition of what is music and what is not escapes me.

The price of a sound system depends on the budget. If it’s a French film or a production with France, I can charge more. For Blu, I worked for free at the beginning, then the film won a lot of awards, was taken on by an agent too, so he paid me quite well for the time. Muto won the Grand Prix in Stuttgart, worth €15,000.00. After that, Blu started saying that he didn’t want to make any money from his films and he decided, halfway through the distribution of Big Bang Big Boom, not to show the film at festivals any more. If you ask him for the film, he’ll say fuck off! and if you ask me, I reply that you can write to him but don’t expect a reply.

Sometimes I ask for the film’s budget and what has been planned for the sound, and if I think it’s right, I accept. If I don’t think the amount is right but the film looks very good, I accept. If the film is average, I say I’ve got something else to do. I’ve never looked for work in sound, there’s always someone who’s asked me. For several years, as soon as I finished one film, I was asked to do another. Now I’m a bit pre-retired. I enjoy working as artistic director for the festival, as well as the workshops.

GS: In the course of watching so many films, are there any trends in music and sound that evolve from one period to the next, or that emerge?

AM: As we move forward, we see a growing sensitivity to sound. Not just technically. There’s more attention than before. We used to complain that it took years to make a film and that only a week was allowed to do the music and the soundtrack. Sound designers are more involved at the beginning of the creative process. We can exchange ideas straight away. More attention is paid to quality, even for student films.

Andrea Martignoni sketched by William Henne (Bucharest, 2015)