TEACHING ANIMATION: OTTO ALDER

Otto Alder: There are three subjects and before we go into these different subjects I’d like to give some ideas about my notion of animation in general and then we can go to the questions of animated documentary, teaching animation and maybe animation festivals.

Everything I say is not based on academic research. My Approach, what I’m talking about, is coming from an experience of working in animation for festivals, teaching, making my own animated films. So it’s more like my personal experiences.

Georges Sifianos: Can you present your career and your evolution?

OA: I will first expose some ideas about animation in general. I will try to put down some ideas about what animation is because then we’ll have an idea of what I am talking about.

For me, animation is a specific form of medium film. Let’s say animation is a subgenre of film but the primacy of the visual design elements is more important compared to live action. Then we have the phenomenon of picture migration or picture motion and, at the same time, the phenomenon of the psychologization of these images, of these visual configurations.

Animation by Michael Frei – Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts

I mentioned the predominance of visual form, which offers endless possibilities for personal expression. And the most important thing, especially when we will discuss animated documentaries, is the distance from reality. Animation has a very clear distance to reality. We see from the first frame on the screen that this is not reality. Particularly in the field of drawing animation, but also in other techniques such as puppet animation, the GEK is a specific configuration of animation. For me, animation is a form of imaginative reflection of reality.

Animation by Michael Frei – Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts

Animation is always grounded in reality, but full of imagination. Animation is a sensual reflection in the form of descriptive metaphors. Thus, animation is not a cinematic reproduction of reality, but a cinematic illusion mediated by imaginative processes as a totality of audiovisual events. Animation is a synthesis of autarchic art forms. So animation is embracing all art forms such as sound, music, fine art, sculpture, architecture, etc. Of course technically we have this clear definition of the frame by frame technique which is different to live action. Animation is a technological variation of cinematographic representations. Animation is a continuous cinematographic montage of single images. However, access to single images is very important and we need to discuss this, particularly in relation to technological developments (digitisation, etc.)

Animation by Michael Frei – Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts

Animation is a rythmityzing of relations between sound and image. There is no original sound in animation which makes a clear difference to live action and which is also very important for the discussion about the documentaries. We can highlight the diversity of artistic options and independent artistic configurations in animation art for the spatio-temporal processes that underlie an artistic idea and in terms of content. Fyodor Khitruk says animation is the shortest way from the figure to mind and from thought to gestalt.

We can now talk about teaching.

Animation by Michael Frei – Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts

I taught at the University of Lucerne. When I started, it wasn’t yet a university, but a high school where studies lasted four years. In 2007, this school adopted the Bologna system: six semesters for a bachelor’s degree and two semesters for a master’s degree. It also introduced the ex-system and modulation of teaching.

My course focused primarily on the history and aesthetics of animation. During the first two years of study, students were required to take courses in the history of animation and the history of film. In addition to these theoretical subjects, they could take many other courses, such as art history, which were not required and which they could choose themselves.

Master Animation – Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts

During the first semester, they had eight interviews with me, each lasting 45 minutes.

The third year was devoted to writing a theoretical thesis on a subject of their own choosing.

When the Bologna-Erasmus programme was launched in 2007, the idea was to synchronise teaching with practical work. The practical course began with drawing animation, then moved on to puppet animation, cut-out animation and other experimental techniques, similar to the way Paul Bush teaches experimental animation, for example. My teaching was very flexible: each of my courses consisted of four highly flexible modules, so that if there was a change in the practical part, I could easily react and adapt my teaching. In addition to the practical part of the teaching, I also tried to integrate real-life situations into the animation. For example, if a film from our school won an award somewhere, we would incorporate it into the course, watch the film and discuss it.

Master Animation – Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts

My objectives were primarily to help students gain self-awareness and, of course, to impart theoretical and historical knowledge and the link between visual and auditory skills. At the end of their studies, they should be able to find their place, both theoretically and practically, in the field of animation. Students must understand that they must be themselves and not follow other ideas or concepts; they must therefore find them themselves.

The teaching methods were very theory-based, but what interested me most was the teamwork. In the end, it seems to me that it was the students themselves who created all the educational content, because from one class to the next, they were given homework assignments, had to research a given subject and present it at the next session. It was also group work, so they formed teams and worked on these subjects not during class, but in their free time.

Master Animation – Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts

My main concern in my teaching was that it should be illustrated by as many films as possible, both classic and contemporary. All these films have always been the basis for discussions during the class. It was actually very interesting to see how the students really took these personal studies to heart and how they brought their own ideas to their learning.

Of course, you all know that technological development over the past 25 years has been very rapid. In the beginning, I worked with 16 mm film, so it was very difficult to obtain copies of the films we were discussing. But with the development of VHS and DVD, up to digital platforms, everything is now widely accessible.

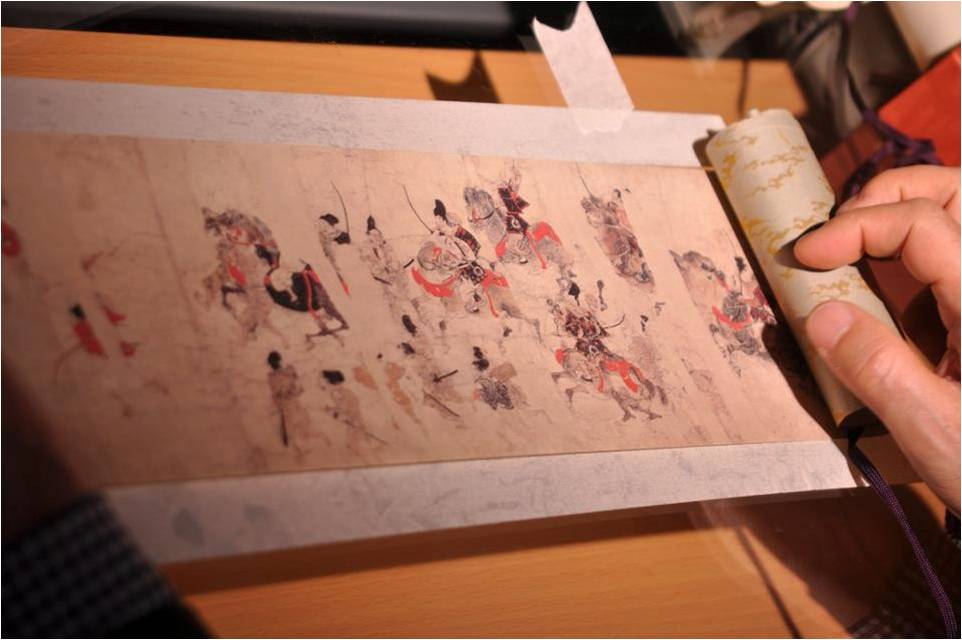

In addition to teaching, I created a library containing a literary canon and a film canon that students could access at any time. They could use them for their own studies and content. Of course, we started with pre-cinema, beginning with cave paintings and scrolls from Japanese art history.

GS: Emakimono.

Emakimono

OA: Yes, exactly. Then, of course, all the optical toys that appeared, technical developments, the genesis of animation from its earliest forms to its beginnings, perhaps with the first American animations.

For sound, I usually invited someone more qualified than myself, who taught the practical aspects of sound.

Then I retraced the history: from the Lanterna Magica to the avant-garde, such as Norman McLaren, the entire historical situation, mainly illustrated by cinematographic examples.

This structure is probably applied in a similar way at other universities.

At first, it was difficult to find someone to teach history. There weren’t many opportunities to exchange experiences. I kind of created my own system, which is modular, flexible and open to students’ ideas.

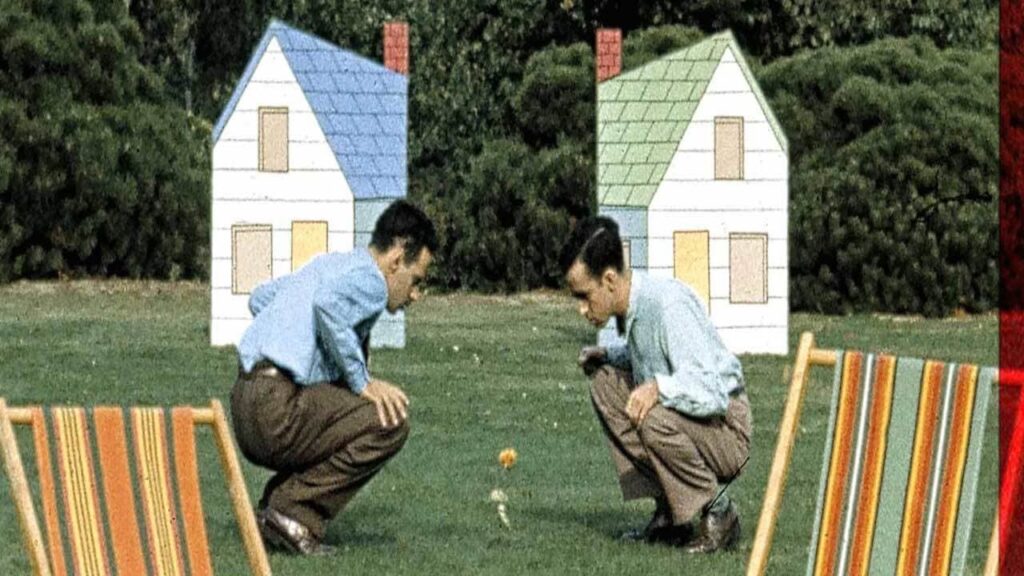

Norman McLaren, Neighbours (Voisins), 1952

Zepe: It was very interesting when you talked about how difficult it was to find films in the 1970s and 1980s. You had to go to the embassies of certain countries to obtain films, such as those from the National Film Board of Canada. At my school, we could watch about ten films a year, no more. Fifty years later, I feel like they show too many. Today, there is so much content on YouTube or Vimeo that if a teacher does not carefully select and present certain films, texts, or other materials based on their own experience, the sheer volume of content online makes it almost impossible for students to form an opinion. I think it’s better to have too little than too much.

Personally, I present films using a non-chronological and non-technical approach, because I believe it is useful to see moving images connected to each specific experience. I do not teach the history of animation from its beginnings to the present day, because that is practically impossible anyway.

Isabel Aboim Inglez: To have History we must have it in right which is what defines History. We put it in right to refer to a certain period of time. So History is made by historians. I don’t know if there are many historians of animation. History of animation should be in a chronological approach on a timeline of events. It is not a reflection on animation. I came from cinema studies and, for me, animation is cinema. How, then, should we think about the representation of the world through cinema? It begins with cinema where we have cinema. Other forms may have existed before, but they weren’t cinema. For me, animation is cinema and it’s a specific form of representation. ‘Real’ images, taken from live action – as they say, because no image is real, as you know – are linked to certain models of representation, more likely to be close to the referent. The difference with animation is that it is close to representation. It therefore offers the freedom to do whatever you want with the medium of cinema. Animation is free cinema. Total manipulation is the freedom to do whatever you want within the frame and to conceive of it in a temporal manner.

Otto said that it’s mainly a visual medium but for me it’s an audiovisual medium and a temporal medium. That’s the difference. It doesn’t stick in the frame, it’s beyond the frame. In cinema I don’t like to have everything in little boxes.

I try to explain to students about creative impulse, and we have different impulses depending on the period, even in cinema. At the beginning of cinema, there was immense freedom to do whatever you wanted with forms and frames. Then, when cinema began to develop its own language, the freedom was kind of put in the right way to do it (this freedom was, in a way, appropriately established?).

In animation, as we can do whatever we like, we can have different times in the same line of story. It’s very creative and the freedom of representation is total. As Jacques Aumont, and also Eisenstein, said, animation is total cinema.

I try to mix these impulses of representation to obtain something abstract, more related to a reference or more plastic and we can also organise things in the manner of live cinema. For me, it’s the same thing.

Esthétique du film, Jacques Aumont, Alain Bergala, Michel Marie, Marc Vernet, 1999

OA: Do you mean in the field of production or in the field of perception?

IAI: In the field of creation.

OA: But when we talk about perception, there are some differences.

IAI: Today, thanks to computer-generated imagery (CGI), nearly two-thirds of images are created by computer.

The model of representation is more likely to be found in the reference or in the representation itself, as Gombrich said.

OA: I would make a difference anyway in the perception. When you see live action, you have the illusion of reality.

IAI: I could give you lots of examples that call this type of board into question. For me Superman is fiction, everything is fiction, documentary is fiction.

OA: I agree about this.

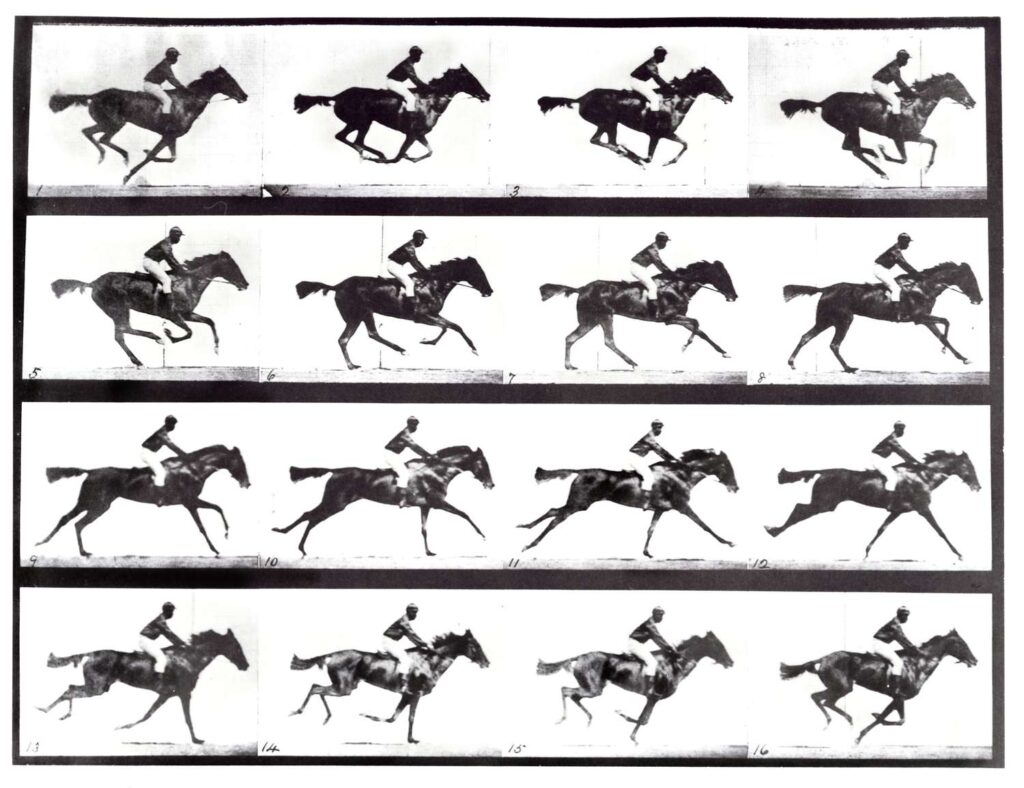

The horse in motion, Eadweard Muybridge, 1878

Z: To prepare for this meeting, Otto sent a selection of films that begins with Eadweard Muybridge’s horse. For me, this raises the key question for this interview: what is a document, what is fiction, and what is animation? It is an excellent starting point for our conversation and for defining what animation is. More than a century ago, movement was suggested, and people could already understand that they were looking at separate photographs linked together. It was a technique that created moving images, but at the time, it was unclear whether it should be considered animation, fiction, or documentary.

Soon after, everything became more concrete. Until the 1920s, cinema as we know it today did not exist; everything was more ambiguous or fluid. Muybridge’s early experiments in Palo Alto already suggested animation that could not be anything other than cinema. As you say, everything is fiction – I agree. You also say that animation is total cinema, but it might not have become cinema as we know it since the 1920s. If not so strongly influenced by fiction, animation could have developed into something completely different.

This is why I always react negatively when people say that animation is just fiction. We are very dependent on fiction juries, live-action film professors, and professionals who work exclusively in live action and dismiss animation as a curiosity. We rarely talk about animation for its own sake. We rarely talk about animation outside of cinema – yet animation does exist outside of cinema.

The horse in motion, Eadweard Muybridge, 1878

IAI: But the definition of cinema does not consist of presenting things in a narrative manner. Like literature, there are many ways to make films. Placing cinema in a casual (action/ reaction) timeline is not good for cinema. It is only one way of making films. Software is designed to do things chronologically, but we can do it differently. When you say that Muybridge’s photographs are the first film, for me, that’s not the case. They are images in motion, but they are not cinema. If I go to a nightclub and see images everywhere, that’s not cinema. They are just images in motion. You can make films without having a three-act story. You can make films like literature or poetry, or like a new romance. I don’t need a beginning at the beginning and an end at the end.

Z: You’re right, but I usually perceive two main ways of defining animation: either as closely tied to fiction and cinema, or as an independent form of expression. It’s strange to define animation as total freedom within cinema.

When I say that Muybridge’s Palo Alto experiments would be interesting to discuss, it’s not because I see them as fiction films, documentaries, or animated films, but simply because they are a starting point for talking about movement. The Horse in motion is not fiction at all. It is, as you say, images in motion. At that time, cinema had not yet been defined.

OA: Muybridge’s Horse in motion is not Cinema, is not animation because at that time cinema was not yet fully developed. It was photography, and Eadweard Muybridge’s initial idea was to prove that this horse did not touch the ground with any of its hooves.

Later, he put the images in order at a rate of 24 frames per second, I think, maybe 12, I’m not sure. He had 24 cameras. When he was able to put those 24 images in sequence and project them, it looked more or less like a cinema film at that point.

La sortie de l’usine Lumière à Lyon, Louis & Auguste Lumière, 1895

But cinema really began with Louis and Auguste Lumière and Georges Méliès. From the outset, they took two different directions: one was documentary, so to speak, and the other was fiction. Both were live-action films. Animation is not live action.

When they saw that they could put photographed reality in sequence in newspapers, they may have realised that they could put photographs in sequence, and perhaps they could put drawings in sequence, and that moment may have been the beginning of animated cinema. Perhaps. I’m not sure.

L’homme à la tête de caoutchouc, Georges Méliès, 1901

IAI: There is Joseph Plateau.

OA: Of course. And Étienne-Jules Marey. This is pre cinema.

We can now speak about animated documentaries.

Cavalier arabe, Étienne-Jules Marey, 1887

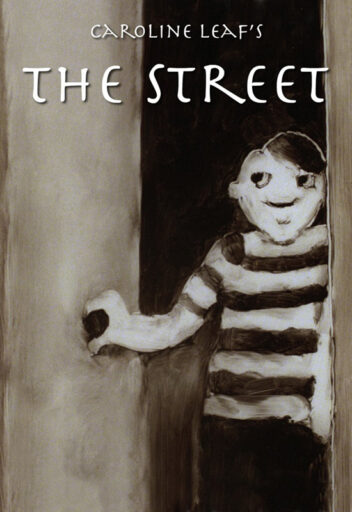

Z: Animated documentaries have become popular today. In the list of films you sent before this meeting, there are films that rely heavily on voice. If we think of The street by Caroline Leaf, The owl who married a goose, or even Conversation pieces by Peter Lord and David Sproxton, the directors used voices. But it is very difficult to classify these as animated documentaries that follow documentary practices. I honestly don’t know how to define an animated documentary. I can tell when a film feels more like a documentary than fiction, but I don’t really know how the distinction between documentary and fiction applies to animation. What we do know is that the processes involved in animation are very different, and that animation can give a documentary a more subjective and unique expression.

In Otto’s selection, I think two films qualify as animated documentaries.

Conversation pieces – Sales pitch, Peter Lord and David Sproxton, 1983

International Leipzig Festival for Documentary (Photo: Friedrich Gahlbeck – Bundesarchiv Bild 183-G1112-0014-001), 1968

OA: I used to work for the festival in Leipzig, which is traditionally a documentary festival, and I was director of the animation section. I don’t know why they also presented animation. Before the fall of the Berlin Wall, it was a very important festival for the German Democratic Republic. However, there was a clash between animated films and documentaries. And when I made the selection for animated films, I realised that many of them had a similar approach to documentaries. So I thought that if I worked in this place where animation and documentary filmmaking meet, I could try to initiate a discussion between documentary filmmakers and animation filmmakers, but it didn’t work out. I didn’t succeed. Documentary filmmakers had serious reservations, perhaps still considering animation to be a field reserved for children.

I compiled a programme of animated films and called it ‘Animated Documentary’. The idea was to show the audience films that straddle the imaginary boundary between reality and fiction. It was at that point that I began to work with the term ‘animated documentary’.

DOK Leipzig in 2002 (Wikipedia)

If we examine these films, which are considered animated documentaries, we can see, as you have already mentioned, that most of them are very wordy, as they are often based on interviews or dialogues. Animation then becomes a kind of tool when visual material is lacking and is used to reconstruct the visual aspect of the documentary, a kind of illustration of the interviews and stories that took place. This is perhaps the main problem with what we might call this “genre”.

But I don’t think these films are documentaries. They are possibly special effects for documentary films.

IAI: These are ‘inside’ films. They are very fashionable and resemble a stream of consciousness, like Virginia Woolf, Clarice Lispector or James Joyce, but for cinema. With this stream, the images flow and the animation serves the stream of consciousness very well. It is a cinematic essay.

Whatever the weather (Bei Wind und Wetter), Remo Scherrer, 2016

Z: In Remo Scherrer’s film Whatever the weather (Bei Wind und Wetter), included in Otto’s selection, the viewer oscillates between things he recognizes and things he doesn’t. The atmosphere it creates—everything about it—feels close to a documentary.

In Das Leben ist eines der Leichtesten by Nyffenegger Marion, something really works. It’s not especially pleasant, but it works. As a hybrid process, it sustains a documentary quality.

In any case, it is very difficult to define what makes an animated film a documentary. How do you define a documentary, Isabel?

Das Leben ist eines der Leichtesten, Nyffenegger Marion, 2019

IAI: I will return to the example of literature: journalistic writing is not literature, but I can approach it in a more literary way. The purpose of writing – I say writing, but I could say animation – is neither journalistic nor historical. It is an artistic introduction to a point of view. Animated documentaries are therefore an original way of looking at and talking about events that could have – I don’t like the word “real” – a historical or geographical reference. It is always the point of view that takes precedence in an original way of talking about it. The street, by Caroline Leaf, talks about death, for instance.

The street, Caroline Leaf, 1976

Z: What attracts me most about documentaries is diversity. A documentary interests me when it presents different points of view and arouses curiosity. It’s not really “a document” in the sense of capturing the right time and place. It’s the opposite: a floating truth that we can never fully grasp. The approach is therefore more open. There is something we can follow, something with its own direction.

By contrast, animation is not a diaristic practice, where you observe, record, edit, and repeat. These fields are so different that I often wonder how they can connect.

IAI: It is a balance between connotation and denotation. In animation, we draw the flow and connection of thought. The approach to events is more on the side of connotation.

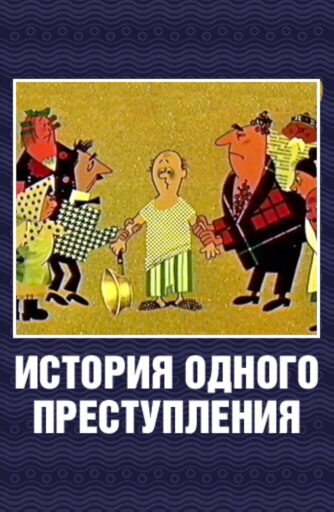

Story of a crime, Fedor Khitruk, 1962

OA: Can we not agree that documentaries are all non-fiction formats, like factual films? There is always a subjective approach on the part of the filmmaker. In the selection I made, there are two interesting films by Fedor Khitruk: one is Story of a crime, which is not a documentary, but Khitruk told me that he had read an article about these events in a newspaper.

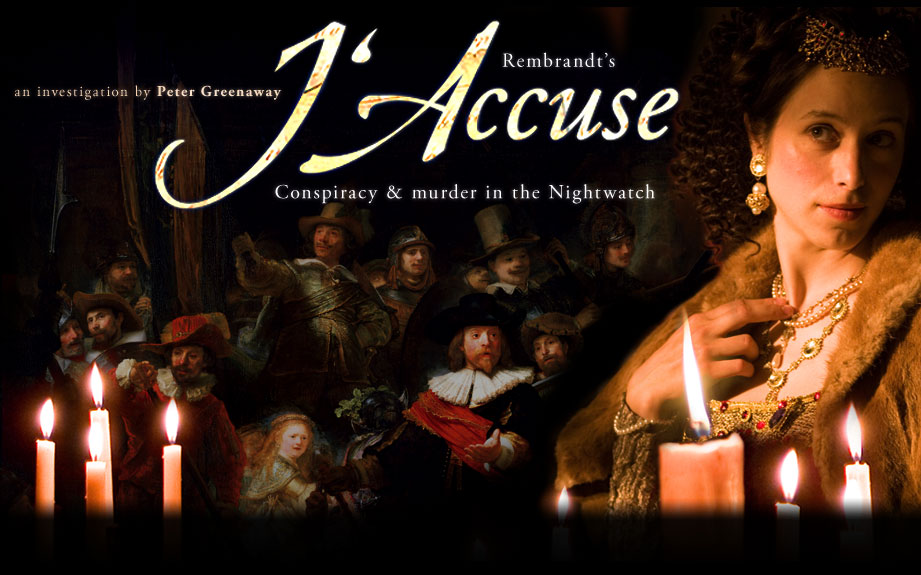

IAI: You know Rembrandt’s J’accuse by Peter Greenaway. He’s also looking for a crime. It could be a documentary done during a retrospective.

Rembrandt’s J’accuse, Peter Greenaway, 2008

OA: Yes!

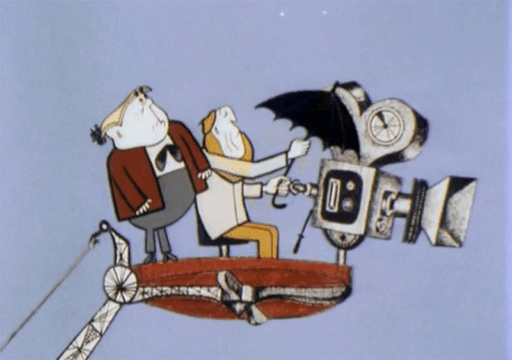

The other film by Fedor Khitruk is Film film film, about animated film making and he told me he got an award in Venice and he met Billy Wilder who told him ‘your film is the best documentation about film making’.

IAI: The balance between the two fields is very difficult to determine. You know, I’m a photography teacher and I don’t believe that photography is a document, even photojournalistic photography. Tell us about a way of seeing things that is perhaps not reality, that is only one reality among others or a possible reality. Only oranges, granny apples or red apples in crates are a document. Photography is not a document because it’s partial.

Film, film, film, Fedor Khitruk, 1968

GS: You have several years’ experience of festivals, which has enabled you to see many films with different approaches. Can you tell us about this experience?

OA: Categorisation is always problematic. Everything is in flow in the combined mix.

Forty years ago, the categories were clearer. That’s no longer possible today. In terms of animated documentaries, all these films have a very individual approach. None of them are identical in the way they are created. And there are a lot of very bad animated documentaries because, as I said earlier, they are very language-laden. They are based on language, which is different from animation, which can tell a story without voice-over or dialogue. Whereas these films, which are mainly language-based, are subject to certain restrictions in terms of distribution, because you have to understand their language. They are mainly subtitled in English, but they are so overloaded with words that you have no chance of following them. At the same time, the images are often very poor and uncreative, with no professional approach. This language problem is the same in live action films. In animation I could observe that most of the films are very language heavy.

Maybe the term ‘essay’ that Isabel brought up is much better than the term animated documentary. On the other hand, a document is always neutral for me. It must be a fact. Animation is not a document for me.

Story of a crime, Fedor Khitruk, 1962

GS: When we speak of document or documentary, we are referring to evidence. Until now, the naturalistic photographic image was considered to be evidence, and this was its main distinction. But today we have images generated by deep fake, animated photorealistic images in motion that we cannot distinguish from reality. Everything is now the same. Everything is “fake”, personally made, subjectively. We need a new definition of the representation of reality. Photographic naturalism no longer has any value as proof. We are in the same field as animation.

Story of a crime by Fedor Khitruk is a subjective way of talking about a crime. It is not proof. What can replace proof?

OA: I like this approach. There are a lot of answers.

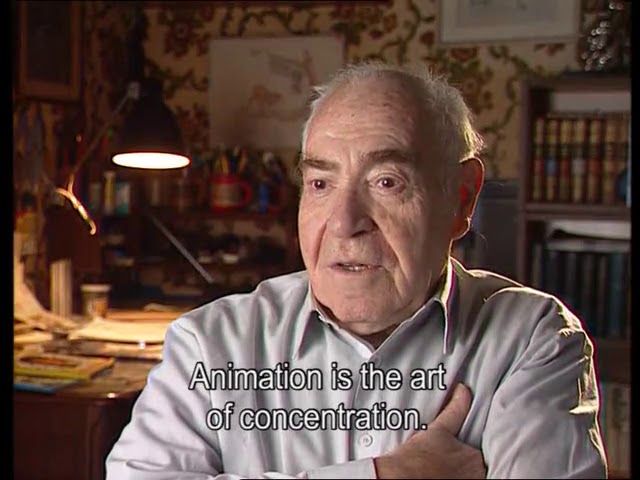

GS: Otto you made a documentary on Fedor Khitruk, The spirit of genius. Can you talk about the relation between animation and documentary? you have this experience concrete.

The spirit of genius, Otto Alder, 1999

OA: I was lucky enough to make this film. My initial approach was to make a documentary about Fedor Khitruk, who is an animator and filmmaker. During the process and afterwards, I realised that it was perhaps an attempt to reach certain conclusions that might be documents. Today, 20 years later, I wouldn’t say that it’s exclusively a documentary film, because I’ve had the opportunity to integrate animation into it, namely the work of Fedor Khitruk, of course, which is far from being a simple document.

There are no more categories. Genres are dissolved or merged into one another. These days you can put everything together: fiction, documentary, animation and so on. And in animation, there is a wide variety of artistic expression, so I still believe that animation is not at all the same thing as cinema, as Isabel said at the very beginning.

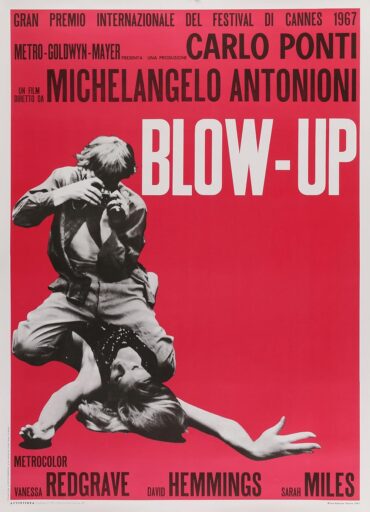

Blow up, Michelangelo Antonioni, 1967

Z: Everyone, now and perhaps always, has been trying to grasp an invisible film hidden within the film itself—as in Antonioni’s Blow-up: the photo is there, a crime has occurred, but you can’t prove it. We are always searching for something that isn’t directly in the film but beyond it. The way people approach fiction, documentary, or animation today creates something close to an unreachable object.

William works with people in prison. Maybe he wants to share his experience.

William Henne: The prisoners talked about the meaning of their sentence from their own point of view. We edited these interviews and they animated puppets in models that show their daily lives. It’s a kind of documentary because they animated their own lives and talked about their condition.

Le sens de la peine, Zorobabel, 2025

GS: Otto, you teach, you’ve organised a festival, you’re interested in theory, you make films. If we reverse the roles, what question would you like to ask Otto Alder?

OA: For the last five years, I’ve had no connection with teaching. My relationship with animation has become more distant. The question is, why did I do all these things?

Z: Animated images are now artificial.

OA: Technology is devouring every genre, from animation to film-making. Thanks to artificial intelligence and good prompts, it’s very easy to make a short film. When my students presented their thesis, they didn’t write it down any more. For me personally, that’s quite dangerous. On the other hand, I see the possibilities of this artificial intelligence. But it is the greatest theft of humanity by technological aristocrats who privatise knowledge and want to sell it on.

Play, Dorothy Pang (made with AI), 2025

IAI: With half a dozen students, we produce hybrid animation projects. And also animated series. I teach the final projects and they can make fiction, documentaries, experimental films and animation. I’m very happy to help them make these discoveries.

Analogue still has its rights. We make paper cut-outs, for example, and photocopies are making a comeback. But they also have a very good approach to digital. They’re not afraid to use it, even with lower quality formats like animated gifs.

Rencontre avec Otto Alder, Fantoche Festival, 2022 (Arttv)

OA: For festivals, artificial intelligence is good because they do not need to have any selection committees anymore.

My professional career in festivals began in 1986 in Stuttgart. I was an organiser and curator and was laid off in 1992. I was then lucky enough to be invited to work for the Leipzig Festival, where I worked from 1993 to 2015. At the same time, I set up Animated Dreams, a festival in Estonia. I left after three years, but it still exists. In 1994 we started to establish the Fantoche festival in Switzerland, which was completely different; it was a collective direction, which is very difficult. That festival still exists, but I’m no longer linked to any of these festivals.

What is the function of festivals? The history of festivals somehow started in 1929.

First Congress of independent film, from 2 to 6 september 1929 in La Sarraz in Switzerland, organised by the Revue du Cinéma, with Léon Moussinac, Walter Ruttmann, Bela Balazs, Sergueï Eisenstein, Hiroshi Higo, Hans Richter, Grigori Alexandrov, Janine Bouissounouse, Édouard Tissé, Jean-Georges Auriol, Fritz Rosenfeld, Alberto Cavalcanti, Moichirô Tsuchiya, Robert Aron and Ivor Montagu (photo: J. Felostein).

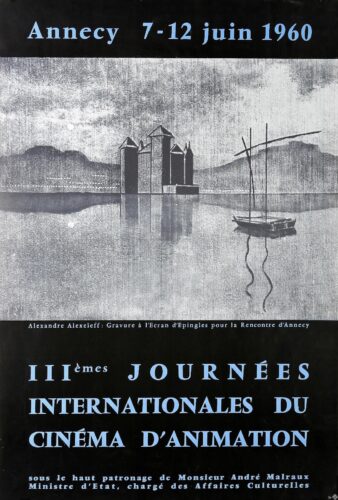

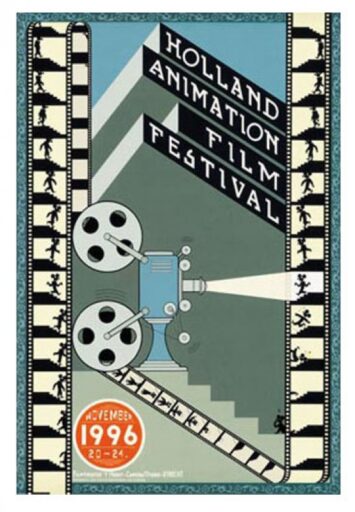

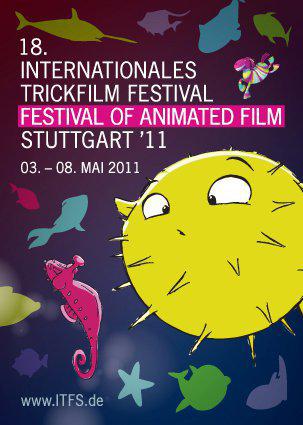

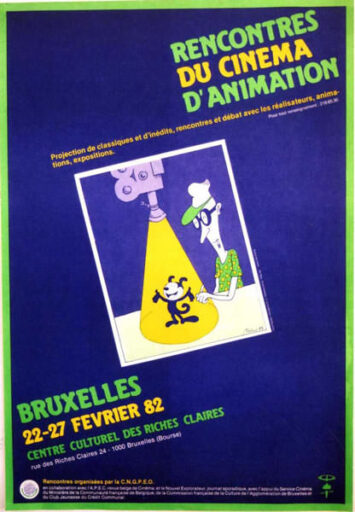

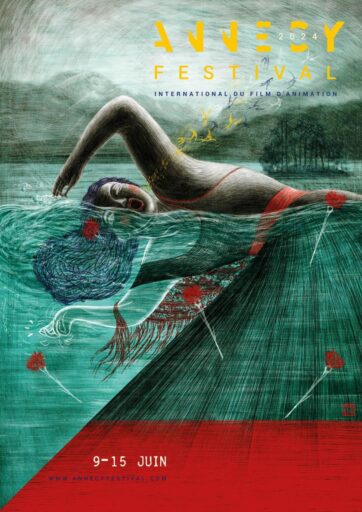

The first independent film congress was held in La Sarraz, Switzerland, with Alberto Cavalcanti, Walter Ruttman and Sergei Eisenstein. They discussed issues related to filmmaking and workshops were organised. A very short film was made, but it no longer exists today. I attended the early days of the festival in La Sarraz. Of course, live-action film festivals such as Venice, Berlin and Cannes had already been established. On the animation side, the history of festivals really began with the creation of the Annecy Animation Festival in 1961, on the initiative of artists and the ASIFA (International Animated Film Association) organisation. Then came Ottawa, Zagreb, Espinho, which was the first annual festival and was created during the Salazar era in Portugal. Then Hiroshima, Varna. They were controlled by ASIFA, which evaluated these festivals. ASIFA had clear rules regarding the selection process, juries, etc. These festivals were controllable because there weren’t very many of them.Later came the Holland Animation Film Festival, Stuttgart, and Brussels. Today, there is not only a tsunami of films, but also a tsunami of festivals. There is no longer any control possible.

ASIFA Prize 2021 recipient Otto Alder and ASIFA Secretary General Vesna Dovnikovic

(Photo: Animafest Zagreb)

Z: ASIFA was formed in 1960. What kind of association is it? Did it come from England, France, Germany…?

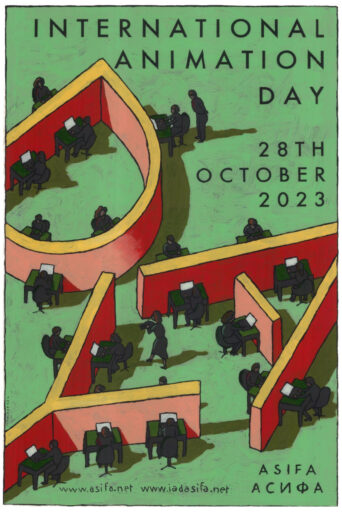

GS: It started in Cannes with an international group of filmmakers and critics, like Norman McLaren, Jiri Trnka, Georges Sadoul, Alexandre Alexeïef… They were not happy about how animation was represented in the Cannes Festival or other live action film festival. They moved in Annecy.

Z: What was the purpose of ASIFA?

OA: They sought to find the ideal venue to present animated films and independent art films in an appropriate manner, without categorising them as children’s films or comedies. They viewed animation as a serious artistic medium for personal expression and wanted to emphasise this aspect. They therefore sought a way to present animation in a concentrated form.

International Animation Day, affiche de Georges Schwizgebel, 2023

GS: At this congress, they discussed the definition of animation and attempted to explore the issue in greater depth. It was also a big family, because at that time, there was a separation between the two blocs during the Cold War, but animation always maintained contact and openness in the space between the two large communities on Earth.

Z: The Italians were greatly influenced by Russian, Polish, and Czech animation directors during the sixties and seventies. In Portugal, a man named Vasco Granja broadcast on national TV a large number of films, especially from the Zagreb school.

OA: What are the functions of festivals?

- They are art exhibitions or temporary artistic events that generally last a week.

- They bring together the most important and recent productions of the past year in a highly concentrated form.

- They are public events that can even bring a city like Annecy to a standstill for a week.

- International festivals are international showcases for the art of animation.

- At the same time, they are entertainment events.

- They award prizes.

- They must stimulate the senses.

- Festivals are spaces for information, communication, discourse, interaction and education, with workshops and master classes.

- They are a meeting place for animation artists, who can exchange ideas.

- They are important venues for the public. Of course, you can watch animations online, on a tablet or mobile phone, but most films are not designed for these media; they are made for the big screen.

It is very difficult to create and maintain a festival. You have to find sources of funding, national, local and regional sources that make up part of the funding, and then there is ticket sales and sometimes sponsorship. If you receive funding from companies, you know that they usually have expectations: they like to be present, they like to be seen, and this can sometimes cause problems. The easiest money to obtain is that which comes from ticket sales and public sources.

Zepe, you live in a country where animation, media and culture in general enjoy a very good reputation, and government officials understand the need to support them. There is no other country in Europe that resembles yours in terms of animation.

Ancien théâtre-casino sur le Pâquier à Annecy (photo: Jean-Pierre Lamy), juin 1963

Festivals are also disappearing. We have recently lost some very important festivals: first, the Holland Animation Film Festival (HAFF), which did not disappear for financial reasons, but because of intrigues within the festival’s board of directors and external influences; Animamundi, which is a typical case of dependence on sponsorship from the large Brazilian oil company Petrobras, which covered about 80% of expenses, but which became involved in political scandals and withdrew its sponsorship overnight; Then there is the very important Hiroshima Animation Festival, which disappeared after the Hiroshima government decided to withdraw all support.

Festivals are a very difficult subject, as we have very little research on them so far.

Holland Animation Film Festival (poster: Chris Ware), 1996

The main issue is, of course, the selection process, which is very influential. Being a director and being part of the selection committee are very influential positions. I always say that a director should not stay in the job for more than 10 years, otherwise things start to get critical. The people who make the selections decide what will be shown on screen and what will not. We are seeing an increase in the number of films. In Stuttgart, they receive more than 1,200 or 1,500 submissions, in Annecy many more. What happens to all the films that are not selected?

Stuttgart Trickfilm International Animated Film Festival, 2011

Festivals have the function of mixing the known and the unknown. Their function is to venture into unknown territory, to experiment and present aesthetic and technical innovations, but also to present the history of animation. Unfortunately, most festivals are not concerned with history, because it requires curation. However, this requires significant financial resources.

The more festivals there are, the more they seem to me to resemble convenience stores.

ASIFA evaluation has completely disappeared. There is no longer any evaluation or control of festivals. There is no longer any criticism of festivals or animated films, with a few exceptions perhaps. When you read articles about festivals, they talk about the number of tickets sold, the number of countries, the number of guests, but say nothing about the films.

Z: In your opinion, which festival best provides opportunities for authors and animation professionals to meet and exchange ideas? Which festivals do you think are most effective at inviting authors to present and reflect on their films?

OA: I would say small is beautiful! Annecy is embracing everything, you get just lost, there is no orientation, it’s not interesting for me. I cannot point out any Festival which is caring about this most.

Z: Animatou is a small festival where you can discuss the films.

OA: Yes. Maybe Fantoche, maybe Anima. There should be more interaction between directors, artists and audience.

There always are two creators of a film: the director and the spectator.

Krok Festival doesn’t exist anymore as far as I know. This festival was quite interesting because it was so intense: alcohol, drinking and partying are part of the festival. There was no possibility to escape, you are really trapped on this boat. The discourse was more easy and effective.

The KROK boat (William Henne, 2011)

Z: Some live-action fiction festivals are more interesting in terms of the questions they ask authors than animation festivals, because I think animation criticism is largely absent. In Portugal, for example, newspapers rarely cover animation. They publish articles on comics, but hardly ever on animation.

GS: Otto, you have launched numerous festivals. I remember the LIAA, which was a very important, one-of-a-kind event. I recognise you as a visionary in the organisation and management of a world centred around animation. The current situation in animation has changed, as there are now many festivals. If you were to launch and imagine an ideal event – I don’t know if you would call it a ‘festival’, but whatever it is – what would it be?

OA: You mentioned the LIAA, the Lucerne International Animation Academy. The idea behind this event was to bring together practice, theory and the public, organised as a symposium rather than a festival with lots of spectators, animations and screenings. We need focus in all areas of life. This project was linked to the university, which funded it. I was unable to continue with it. My dream was to organise this meeting every three years, but I failed, perhaps because I have no university education and the money, which was intended for research, came from the university. Research was the objective of the LIAA, and the school did not continue to fund the project. It’s a shame, but it was very interesting to do it once, and there were wonderful presentations and discussions. The feedback was excellent, but that’s in the past.

Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts, School of Art and Design

GS: For me, it was one of the best events in my life.

OA: Thank you very much!

Z: Would you do it again if you had the funding – or not?

OA: Yes, but I no longer have the strength or energy to manage the financial side of things.

For the first conference or symposium organised by the LIAA, the theme and main content focused on storytelling and dramaturgy in animation. It would be interesting to organise a conference on animated documentaries, for example. The idea for the theme of the next conference was the sound and visual aspects of animation, as the auditory part of animation is still neglected in both research and practice.

The question of selection is problematic: what kind of people do the selecting? I have sometimes been part of a selection committee and wondered what people’s conception of animation was; they could have completely different approaches, which can be a good thing. But on the other hand, it can also be critical in many cases. In no festival are aesthetic and technical criteria really emphasised.

Another issue is censorship: the European Media programme, which funds European festivals, requires that at least 50%, or even more, of the films presented at festivals be of European origin. And suddenly, the question arises as to whether we can accept this film, because we have too many non-European films.

1st edition of the Brussels Animation Film Festival, known at the time as Rencontres du Cinéma d’Animation and later renamed Anima (poster: Philippe Moins)

Z: At fiction, documentary, and animation festivals everywhere – including Portugal – jury selection often depends on criteria. Films must meet a certain number of points to qualify. It’s not about language, expression, or narrative; it’s about trends or recent events. For instance, if you make a film about Gaza, it will almost certainly be selected.

In Portugal, many filmmakers choose historical Portuguese subjects or texts because it improves distribution. But this empties expression in animation. Everyone complains – even the juries.

Bill Plimpton (photo: Kate Walter)

OA: Some artists suddenly become very popular. For example, Bill Plimpton was present at all the festivals at one point, then he suddenly disappeared. Then a new star was born. It’s a star system, like in live-action films, and animation doesn’t usually have a star system.

Given the number of films, if you have to watch 1,200 of them, I don’t know how festivals manage to view them, integrate them or select them for their competition programmes. Nowadays, it is also fashionable to have themes for competition programmes. Films are grouped together by the festival under the same banner, and directors have no say if they feel their film does not fit.

The length of films is a topic of discussion within the selection committee. A 30-minute film takes the place of shorter films.

Z: There is contamination between juries, producers, media, and teachers. The same people have been in these positions for years, making it very difficult to break these links. Everyone knows it, but no one talks about it.

Festival International du film d’animation d’Annecy 2024 (poster: Regina Pessoa)

OA: Another example: some years ago Annecy festival took out the more experimental films from the international competition into a special competition with a nice name, ‘Off limits’. But it’s animation and it should not be separated, it should be integrated in the big competition. And if you criticize this, the director will never talk to you anymore.

IAI: Festivals take into account the quality of the animation, the drawing and the plasticity. But an author like Phil Mulloy doesn’t have such good drawing skills. They don’t see beyond the technical aspects of the animation. I generally prefer my films to participate in live-action film competitions, as the audience is more receptive to all types of cinema. At animation festivals, they say ‘It’s not well drawn, it’s not very well animated, let’s make animation great again!’ I will wear the cap next time!

Intolerance I part 1, Phil Mulloy, 2000