TEACHING ANIMATION: CHIARA MAGRI

Georges Sifianos: Could you introduce yourself and the school?

Chiara Magri: My name is Chiara Magri, and I work at the National Film School in Italy, Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia in italian. Our animation course, based in Turin (Northwest Italy), was a break with tradition, as most film courses had been held in Rome since the 1930s. While animation had a small presence at the school in Rome, it was more of a permanent workshop where a few passionate students pursued their creative aspirations.

Giulio Giannini, who initiated the animation course in the 1980s, was the partner of Emanuele Luzzati. Together, they produced beautiful short films and title sequences. However, Italy had no real animation industry at the time. The school aimed to preserve animation as an art form rather than prepare students for professional production since there were limited opportunities beyond advertising. Italian television primarily purchased animated content from the U.S. and occasionally from European productions but did not produce much domestically.

When we proposed launching an animation course in Turin, our project was built on a shifting industry landscape. By the late 1990s, the emergence of a domestic animation industry became more feasible, thanks to European Union policies, such as the MEDIA program, which required broadcasters like RAI to produce European animation. This created a demand for skilled professionals, but there was no workforce to support it. So, in 2001, we designed a course to train young professionals for this starting industry.

We had no prior experience in structured animation training—outside of the very seminal experience of the workshop in Rome, there were virtually no animation schools in Italy. However, it became a strength. We approached the challenge with humility and learned from countries where animation education was more established. I had the opportunity to participate in the Training for Trainers program initiated by CARTOON in Brussels, where I engaged with experts in animation education. It was an invaluable experience, and it’s a shame that such programs no longer exist.

We began with a small group of 12 students per year, selected through a rigorous admissions process. Our students, especially in the early years, were highly collaborative, and together, we shaped the school’s identity. This collaborative foundation is one of the reasons we are now recognized as a leading animation school in Italy.

We also had the opportunity and the luck of motivated professionals who devote some of their working time to the school. Everyone was saying: “If only I had a school like this when I was starting out!” My words may sound sentimental, but in animation, motivation is essential—you can’t create animation without it.

Over the past 20 years, our school has evolved significantly. Initially, we had a flexible budget that allowed for experimentation and, importantly, mistakes. Unfortunately, financial constraints today limit that freedom. Another major change came four years ago when the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of University granted our diploma a new status, complicating our structure. We are not officially part of the university system, yet we must assign academic credits, which contradicts our practical, informal teaching approach. This is a common challenge among European animation schools, though some have faced it earlier than we have. The main difficulty lies in helping students understand that while our diploma is legally recognized, our school is not a traditional university—especially in Italy, where universities are predominantly theoretical rather than practical.

Despite these challenges, applications continue to grow, allowing us to be more selective. Our three-year program remains highly practical, with all instructors being artists and being active industry professionals. The duration from the workshop in Rome last two-year, we started a three-years course in Turin. Today, we accept 20 students per year. Our curriculum balances two objectives: preparing students for industry roles by training them in key techniques (primarily 2D digital animation and some 3D) while also fostering artistic expression to nurture new talents in animation. This dual focus is not easy to maintain, especially as students become more influenced by mainstream trends and struggle to conduct in-depth research beyond what’s immediately visible online. The internet provides a vast surface of information, but going deeper is increasingly challenging. Finding one’s unique artistic voice is harder than ever.

La Luna rubata, Vittorio Massai, Dario Lo Verme, 2017

GS: Could you elaborate on your teaching methodology?

CM: Our main aim is to enable students to work in a studio. That’s why much of our curriculum is dedicated to key industry processes: storyboarding, animation, and background design. We focus on digital tools, mainly Toon Boom Harmony, teaching students not only the techniques but also the discipline required for professional work—such as meeting deadlines. Sometimes, we have to push students toward industry standards, which may conflict with their creative instincts, but ultimately, we want to help them find a job.

There is a widespread fear among young animators that they won’t find work in Italy and will have to move abroad. This isn’t entirely true. Italy has a real industry producing children’s TV series, and there is plenty of work available.

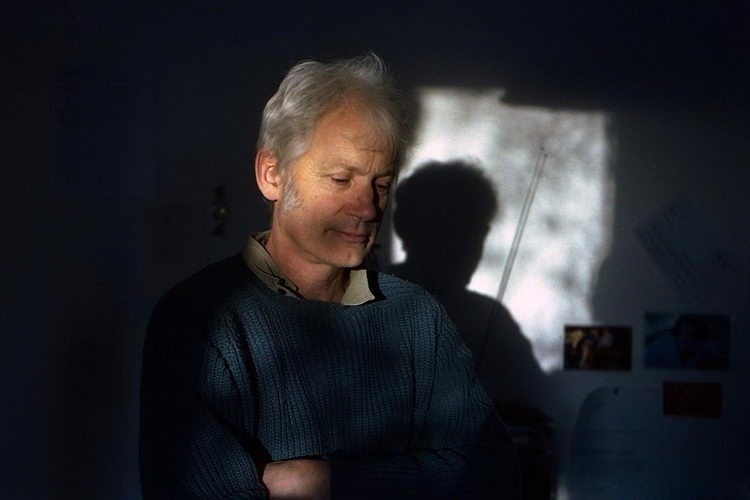

During the first two years, students also take short, intensive workshops—one to two weeks—with independent animation artists, often from abroad (budget permitting). These workshops expose students to diverse creative perspectives. We were fortunate to work with Paul Bush, whose contributions were invaluable. His passing in 2023 left a profound gap in our program. He conducted workshops on directing animation and idea development and mentored students on their diploma films, which is the core project of their third year.

Paul Bush

Our curriculum progresses over three years. In the first year, students receive foundational training, mainly in 2D animation, as they often want to start by drawing on paper. They also receive an introduction to film language and directing. We don’t have a dedicated screenwriting course because we select students based on their visual creativity rather than writing skills. Instead, we teach them to develop projects through an interactive process—moving between writing and drawing rather than following a strict script-to-storyboard path. Ideally, we would one day introduce a screenwriting course where writers collaborate with animators, but we aren’t there yet.

The diploma film is a major challenge. We encourage originality and personal expression, yet students must work collaboratively, often co-directing their films. While this sometimes dilutes individual artistic identity, it fosters teamwork, which is one of the most valuable skills they take away from our school.

Humus, Simone Cirillo, Simone Di Rocco, Dario Livietti, Alice Tagliapietra, 2017

We ask each student to propose an idea for a short film. While this is not mandatory, all 20 students usually take part, both in group and individual sessions. They begin by writing a short script—about one page long—and developing some initial visual concepts and drawings.

The first step is a pitching session, where each student presents their project. Together, we make an initial selection, typically narrowing it down to 10–12 ideas for further development. Each of these students continues refining their script and visuals individually, while those without a selected project contribute through visual research for the projects they find most compelling. However, they are asked not to interfere with the storytelling or writing process. This stage lasts about two months—quite a short time.

After this period, we hold a final pitching session to select the six projects that will move into production. While we try to involve students in the decision-making process as much as possible, the final choice ultimately rests with me and the three teachers.

Once the six projects are chosen, students form production teams. At this point, projects often undergo significant transformation, particularly in their visual style, as team members contribute suggestions and ideas. Each student takes on a specific role, and directing responsibilities are shared. This collective approach can sometimes dilute the personal vision or originality of a film, but it is invaluable for learning collaboration, teamwork, and mutual support. Interestingly, few students have the confidence or determination to assert themselves fully as directors.

In some cases, when a student demonstrates exceptional reliability, motivation, and a strong personal vision, we allow them to develop a film individually. This approach has led to notable successes, such as Donato Sansone and Martina Scarpelli. However, it has also resulted in unfinished projects, as working alone presents unique challenges. Individual films remain rare within our program.

Love cube, Donato Sansone, 2002

Cosmoetico, Martina Scarpelli, 2015

William Henne: It’s interesting that the school invites filmmakers. Students also engage with professionals from the industry.

CM: This dual approach is a fundamental aspect of our school, but it requires significant time and financial resources—both of which are increasingly rare. We are constantly struggling to maintain this balance.

We would be ready to introduce a Master’s program following the BA [Bachelor of Arts], but this would require additional funding. We would need to be internationally oriented if we were to attract enough students for a Masters degree. Such a program could focus more on authorship and independent filmmaking, giving students extra time to develop their portfolios and industry connections. Those interested in creating their own films could benefit from a two-year course dedicated to this goal.

Currently, we remain the only public institution in Italy fully dedicated to animation. This allows us to keep tuition fees relatively affordable—currently €3,000 per year, which is quite reasonable compared to private schools. Many institutions now offer animation courses, often combined with illustration, but they tend to focus on technical aspects such as 3D animation and character animation, rather than animation as a storytelling medium.

We haven’t yet touched on the impact of AI and the digital revolution. One thing is certain: innovation will always be necessary. Our role is to experiment and explore new creative possibilities.

GS: The school is called Centro Sperimentale. Is it connected to that idea?

CM: Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia literally means Experimental Center for Cinematography, not Center for Experimental Cinematography. Mussolini created these experimental centers because they were highly innovative, like the Experimental Center for Agriculture. Today, the center’s main goal remains the development of filmmakers and authors.

Animation is particularly interesting because it raises fundamental questions: What is cinema? What are its languages? It also embodies the contradiction between industry and art. Animation provides a unique opportunity to explore what it truly means to create art or entertainment.

GS: There is now a strong tradition of animation in Italy, with important directors like Toccafondo, Catani, Blu, Simone Massi, Donato Sansone, and Martina Scapelli. On the other hand, there’s the industry, which relies on standardized tools like Toon Boom and a structured production process that starts with a storyboard.

CM: We try to teach our students how to use these tools—Toon Boom or TVPaint—in the most creative and personal way. One of the most common comments about our graduation films is, “Oh, how different they all look in style!”—even when they’re made with the same software.

Unfortunately, we don’t have extensive facilities for stop-motion, which limits our ability to explore it fully. We encourage students to experiment with puppets, but they often lack confidence when trying different techniques.

What I notice in our films, compared to those from other European schools, is that in Italy, there’s a deeply ingrained notion of classical beauty. Even students who struggle with drawing aspire to draw like Michelangelo. This mindset makes it difficult for them to push boundaries. The weight of classical beauty is so deeply rooted—almost subliminally—that it acts as a constraint on creativity. We don’t see much expressionism in our work. The Italian emphasis on beauty, harmony, symmetry, and proportion can be a kind of creative chain.

At the same time, we also teach students how to manage production pipelines—an essential skill, even for independent filmmakers. Those who create their films individually eventually develop their own workflow, because they learn a structured approach to animation.

Midori, Elena Garofalo, Marta Giuliani, Laura Piunti, 2017

GS: What is the selection process for new students?

Toccafondo never uses a storyboard. The requirement to use one can push films in a more standardized direction. Similarly, software like Toon Boom encourages clean lines, filled-in colors, and a certain type of character design. Do you have any teaching methods to counteract these tendencies?

CM: Our student films are ambitious, but we still emphasize traditional storytelling. There are two types of animation schools: film schools and art schools. Paul was very insistent on developing strong storytelling in films, and in some ways, industry methods support this. While these methods may limit creativity, they also make it easier to focus on storytelling fundamentals—a clear beginning, middle, and end. Surprisingly, not many students even aim for that.

A film isn’t a game—it’s a structured narrative, and engaging an audience is crucial. That’s what we teach. I’m not sure if this approach will be relevant in the future, given that entertainment is increasingly built around 30-second clips. But we still think in terms of the big screen, the silver screen, film festivals, and the power of conveying a message through cinema—regardless of its form.

La cabina, Ginevra Lanaro e Federica Di Leonardo, 2017.

In a way, we prioritize content over form. The standard production framework provides students with a sense of security while making their films. They work in teams, where the workforce naturally supports the director’s vision. I agree with you—it would be a dream to create a master’s program where students, after learning the standard production method, gain the confidence to break the rules.

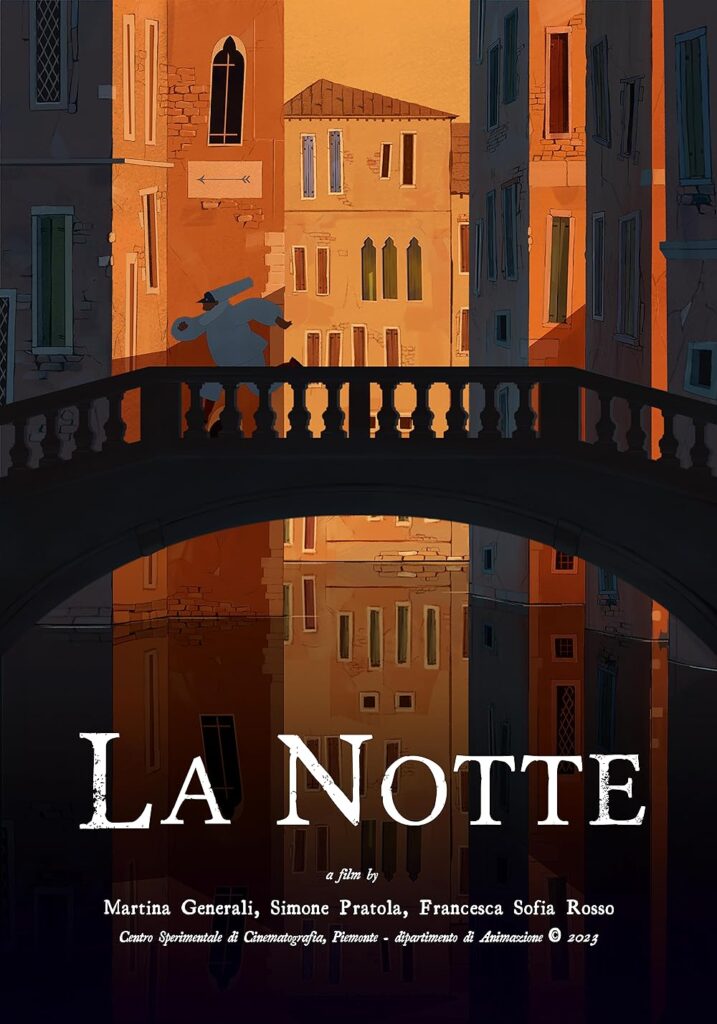

Even our most “art house” films tend to be quite traditional. In 2023, we won the Cristal d’Annecy for La Notte. I was really surprised. The three directors did an incredible job, with strong animation and appealing characters, but the film wasn’t experimental at all. Everyone enjoyed it—children, artists, even experimental filmmakers. The music of Vivaldi was the driving force behind the film.

When the student initially proposed a film about Vivaldi, Venice, Carnival, and Pulcinella, I thought, “Oh no, please!” But in the end, he had a very clear vision and was excellent at pitching the project.

La Scuola del Libro, a very important school in Urbino, specializes in art publishing, engraving and illustration. It has produced renowned filmmakers like Toccafondo, Catani (who now teaches there), Simone Massi and many other very important filmmakers. But as with any school, it tends to imprint a certain style on its students. It’s paradoxical—schools should encourage creative freedom, yet students often end up imitating their mentors.

La notte, Martina Generali, Simone Pratola, Francesca Sofia Rosso, 2023