ACTING IN ANIMATED FILMS

Georges Sifianos

Between identification and distanciation

A: Acting and its characteristics

An actor’s ‘acting’, like that of a child, is an imitation, in other words a mimesis. It’s a question of ‘pretending’, taking a step away from reality and creating an a priori protective distance. In both the animal and human worlds, this is generally used for learning, but also for relaxation. By simulating actions, we study them, understand them better and, by becoming familiar with them, tame our fears. This can lead to emotional relief, the catharsis of tragedy. Acting makes the drama of reality metaphorical and extends the play of childhood. As children we play directly, as adults we continue this activity, but more by proxy. In both cases, the mental activity is no different, since we now know that the same brain centres are activated when we do an action, when we think about doing it or when we watch someone else doing it. [1]. However, although the mimetic principle is the same, the processes of play in theatre, film and animation do not coincide. While provoking empathy, animated acting develops its own range of variants.

In theatre and film, the fact that an actor is imitating is clearly identifiable. Less obvious in animated film, ‘acting’ manifests itself through two distinct means of expression, image and movement. To analyse this acting, it is necessary to assess their respective contributions.

[1] This is the conclusion of the discovery of ‘mirror neurons’. Giacomo RIZZOLATTI, Corrado SINIGAGLIA, Les Neurones miroirs, Odile Jacob, 2011.

[back to text]

The contribution of image

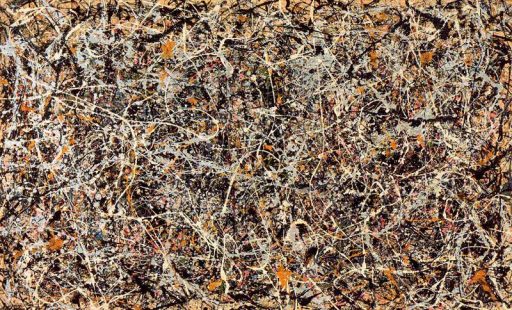

As far as the image is concerned, we knew it intuitively, but Vittorio Gallese and David Freedberg [2] have also demonstrated it: an image carries within it the traces of its creation. Faced with a Pollock dripping,

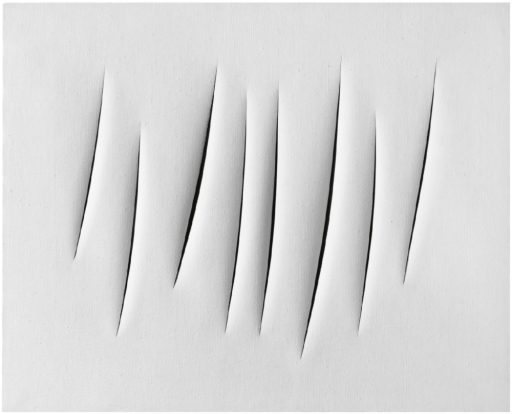

or a Fontana lacerated painting,

or any drawing, we mentally invoke the action that left these traces. Generally speaking, an image carries a range of information through the dynamics of the shapes, colours and textures that make it up and the references associated with it. In this way, it carries an emotional charge, and every graphic imprint bears witness to the process of its creation.

[2] Vittorio GALLESE and David FREEDBERG, « Motion emotion and empathy in esthetic experience », Trends in Cognitive Sciences, May 2007, vol. XI, n°5, pp.197-203.

[back to text]

The contribution of movement

As far as movement is concerned, we can ask ourselves whether all movement is linked to dramatic acting. Of course, as is the case with images, all movement carries an expression, but when an actor is active, he can essentially produce information about his movement from point A to point B without any significant emotional implication. This is also the case for a drawing or any animated object. Movement in animated film can also be content with a rhythmic and musical expression without any psychological intention. A typical example is Norman McLaren’s Caprice en couleurs [3], in which coloured shapes, lines and textures vibrate, alternate and move. This type of movement provokes in us changing sensations of ‘visual music’. Conversely, a movement of abstract forms can become a game with intentions and psychology. This is what we see in another McLaren film,, Rythmetic [4] :

Here, numbers involved in arithmetical calculations are distorted, moved, grouped together and interact. An ‘undisciplined’ and ‘recalcitrant’ number makes a mess of things, forcing the others to put it back in its place… Sometimes the movement of these actions is so precise that we can’t help but attribute psychological characteristics to these moving figures, a mischievous personality for example… The way they move leads us to believe that there are intentions behind each of their movements.

On the other hand, movement in the cinema can be evidence of an intention on the part of the director rather than the character, as in certain camera movements in space that precede an action that guides the viewer’s attention…

[3] Caprice en couleurs, film by Norman McLaren and Evelyn Lambart, 7 min, 1949.

[4] Rythmetic, film by Norman McLaren and Evelyn Lambart, 9 min, 1956.

[back to text]

From movement to acting

If, as we have seen, there are no clear boundaries between acting and movement, we can ask ourselves at what point movement in an animated film becomes acting. According to Michotte Van Den Berck, when two unrelated elements, two cycles for example, move synchronised in parallel trajectories, they give the impression of an internal link.

This link disappears as soon as they embark on independent trajectories [5].

In other experiments, Michotte created the impression of the characteristic movement of a caterpillar by stretching and moving simple rectangles [6].

As we have seen, movement is capable of conveying more information than that which concerns the simple movement of an element in a space.

But the most elaborate demonstration is that of Fritz Heider and Marianne Simmel [7] who, in 1944, created a short film using a circle and two black triangles, one smaller than the other, and the outline of a much larger rectangle, a section of which could be opened and closed like a door. The first three shapes moved in different directions and at different speeds, chasing each other and interacting within and around the rectangle, opening and closing its entrance.

Reactions from spectators collected on questionnaires described some of the movements of the triangle as aggressive, quarrelsome, clever, evoking an irritable temperament, a love of power, or described the other shapes as timid, cunning, devious, always on the defensive… These descriptions showed that spectators interpreted the movements of the geometric shapes as the actions of living beings or people in most cases. Reacting to the same experiment, spectators even imagined dramatic narratives based on these movements, such as the rivalry between two men over a girl [8]. These experiments demonstrated that intentions can be attributed to simple moving forms, which even take on personalities depending on the nature of their actions. This leads us to the conclusion that, when mobility suggests an intention, it is possible to speak of play and, failing that, of movement.

[5] Albert MICHOTTE VAN DEN BERCK, « La participation émotionnelle du spectateur à l’action représentée à l’écran. Essai d’une théorie », Revue Internationale de filmologie n° 13, 1953.

[6] Rudolf Arnheim describes this experience: Michotte used a horizontal bar of the proportions 2:1, located at the field’s left. The bar starts getting longer at its right end until it has reached about four times its original length. As the right end stops, a contraction begins at the left end and continues until the bar has become as short as it was originally. Now the left end stops, the whole performance starts all over again and is repeated three or four times, which carries the bar to the right side of the field. […] the effect is very strong. The observers exclaim : “It is a caterpillar ! It moves by itself !” Rudolf ARNHEIM, Art and visual perception, London, University of California Press, 1974. 50th anniversary printing, 1997, pp. 398-399. There are other examples in this book.

[7] Fritz HEIDER et Marianne SIMMEL, « An experimental study of Apparent Behavior », American Journal of Psychology, Apr.1944, vol. LVII, n°2, pp.243-259.

[8] A man has planned to meet a girl and the girl comes along with another man. The first man tells the second to go; the second tells the first, and he shakes his head. Then the two men have a fight and the girl starts to go into the room to get out of the way and hesitates and finally goes in. She apparently does not want to be with the first man. The first man follows her into the room after having left the second in a rather weakened condition leaning on the wall outside the room. The girl gets worried and races from one corner to the other in the far part of the room.

HEIDER et SIMMEL, ibid, pp. 246-247.

[retour au texte]

Dissociations

Nevertheless, acting in animation is characterised by a number of other differences, because while a flesh actor and his character form a unit [9], en animation on observe des dissociations sur plusieurs niveaux :

- between the actor who plays (animator) and the actor-effigy;

- between the image and the movement of the effigy;

- at the level of the micromovements of flesh and texture;

- between the bodies and the sets;

- between the time of the play and the time of its creation;

- and also the possibility of collaborative play within a character.

We will examine these different cases.

Dissociation between the actor (the animator) and his effigy.

Acting is a process, not an automatism. Whose intention is it? Who is playing the game? These are important questions, because there is a difference between the performance of a real actor and that of an artefactual actor. In theatre and film, a real person identifies with the performance. Behind the play, it’s the actor who is obviously there. In animation, a wide range of figurative and abstract forms assume this appearance [10]. The unity between the figure and its movement is accepted but not acquired. Movement is not inherent in a drawing as it is in the living. It is the difference between a literal body and a metaphorical body, a body that imitates directly (that of the actor, or dancer…) and a body that imitates indirectly (that of the animator). In animation, there is a fundamental dissociation between the moving figure and the source of the movement, because the image of the animator is generally not present [11], which leads to perplexity for the spectator who perceives the game but not the player.

An important issue arises here, because an actor’s real body has its limits. Approaching them creates dramatic tension. The actor’s self-transcendence is a source of emotion. An animated figure, on the other hand, is not subject to gravity or fatigue. It has no limits to reach and its action has nothing to do with a performance that provokes emotions by surpassing itself. While live-action acting is based on reality, acting in animation is based directly on metaphor. So although we can ‘identify’ with an animated figure, its performance does not trigger the dramatic tension of an actor challenging his limits. The real or artefactual nature of the actor creates an initial emotional conditioning [12].

[9] Of course, editing makes it possible to obtain hybrid beings: a stuntman replacing an actor for a dangerous scene, or the agile hands of a draughtsman in place of those of the actor playing the painter. In all these cases, cinema generally seeks to conceal its subterfuge.

[10] Animated films use a wide range of representations, from photo-naturalist images to minimalist and abstract representations. The stakes are different in each case. However, as this text cannot cover every possible variation, we will limit ourselves to a non-exhaustive list.

[11] It is possible for an animator to animate his image or, once his effigy has been modelled, to animate it in real or delayed time. But we’ll stay with the most common cases.

[12] To situate ourselves in relation to Bazin’s rule of ‘’montage interdit‘’ (‘forbidden montage’) and the example he uses, if the condition for the credibility of a scene is the presence of the child and the horse (or the crocodile and its next victim) within the same frame, in animation this effect of realistic presence is of little value. The raw material of animated film is not a ‘copy of reality’, but an immediate metaphor. Réf.à André BAZIN, Qu’est-ce que le cinéma ? « Montage interdit », Paris, Éditions du Cerf, 1985, pp.49-61.

[back to text]

Dissociation between the image and the movement of the effigy.

Cinema automatically records images and movements, creating a unity that simulates reality. Animated film, on the other hand, dissociates images and movements and their mimetic expressions by default. Sometimes the illusion produces coherence, sometimes reasoning imposes separation. The imitative value of photography is obvious, but not so for drawings, especially non-figurative ones.

Dissociation at the level of the micromovements of flesh and texture.

Living skin moves according to bones and muscles. The surface of an animated figure has no similar structure. The painted texture is ‘contained by’ rather than ‘rooted in’ the figure, retaining its autonomy and independent expression. The paradox of the need for a gap between image and sound, when lips-sync is used, bears witness to this: when you speak in a cartoon, it has been observed that perfect synchronisation of the sound to the shapes of the mouth creates the paradoxical feeling that the image is lagging behind the sound. If you desynchronise the sound by delaying it by one to three frames, you get the impression of perfect synchronisation [13]. Since figure movement and texture movement are independent in animation, we can apply autonomous, similar or ‘counterpoint’ expressions to them. There can be calm figure movement and calm texture, or calm figure movement and agitated texture. Each time the emotional quality of the performance will be different.

The relationship between bodies and sets.

Edgar Morin, quoting Bilinsky, notes that ‘on the screen, there is no more still life: it is as much the gun as the hand and tie of the murderer who commits the crime [14] ‘. If the landscape is a key player in the Western, and a torrential downpour in a film can serve as a metaphorical backdrop for a character’s feelings [15], animated cinema is capable of going even further: the set can literally become an actor, as in the forest scene in Walt Disney‘s Snow White (1937)where branches and trees become anthropomorphised…

in the film Tutu by Pascal Dalet and myself (2000), a group of buildings bend down to watch a scene in the street in fear…

Or the set can play an important role, changing context as it goes along, as in Raimund Krumme‘s minimalist film Seiltänzer (1986), where the rectangle of the set becomes a trapdoor, a panel, a mirror, etc., depending on its position in relation to the two characters in the film. In other cases, the simultaneous organisation of the shapes, textures and movements of characters, objects and sets can be likened to a musical orchestration. This is the case of the films Fugue (1998) by Georges Schwizgebel or Désert (1981) by José Xavier.

[13] Richard WILLIAMS, The Animator’s Survival Kit, Faber and Faber, 2001, p.310. This phenomenon is noticeable in cartoons, but not – or much less so – in live-action cinema, where image and sound do not need to be out of sync to appear synchronous. The explanation for this paradox is that in live action, we have information coming from the micromovements of the skin that announce the forthcoming movements of the mouth. This is not the case in cartoons, where the movement information is conveyed by lines that delimit the shapes and whose colours are often flat without texture. The same procedure for synchronisation applies to characters made from modelling clay or computer-generated images. Although these techniques are potentially more naturalistic, they do not provide information about the changing continuity of the underlying bone and muscle structures, as is the case with real images.

See also Ollie JOHNSTON et Frank THOMAS, The Illusion of life : Disney animation, NY, Abbeville Press, 1981, p.461. Another author, Shamus Gulhane, notes the need for a two-, four- and sometimes five- to six-frame time lag for actions. Shamus GULHANE, Animation: From Script to Screen, London, Columbus Books Limited, 1988, p.210.

[14] Edgar MORIN, Le Cinéma ou l’homme imaginaire, Paris, Les Éditions de Minuit, 1956, p.79. Boris BILINSKY, « Le Costume », L’Art cinématographique, t. VI.

[15] Bernard-Marie Koltès underlines the finesse of this interaction in a short text entitled ‘Un hangar à l’ouest’ (‘A hangar in the west’):

Imaginez qu’un matin, dans ce hangar, vous assistiez à deux événements simultanés ; d’une part, le jour qui se lève, d’une manière si étrange, si antinaturelle, se glissant dans chaque trou de la tôle, laissant des parties dans l’ombre et modifiant cette ombre, bref, comme un rapport amoureux entre la lumière et un objet qui résiste, et vous dites : je veux raconter cela. Et puis, en même temps, vous écoutez le dialogue entre un homme d’âge mûr, inquiet, nerveux, venu là pour chercher de la came ou autre chose, avec un grand type qui s’amuse à le terroriser et qui, peut être, finira par le frapper pour de bon, et vous dites : c’est cette rencontre là que je veux raconter. Et puis, très vite vous comprenez que les deux événements sont indissociables, qu’ils sont un seul événement selon deux points de vue ; alors vient le moment où il faut choisir entre les deux, ou plus exactement : quelle est l’histoire qu’on va mettre sur le devant du plateau et quelle autre deviendra le décor ? Et ce n’est pas obligatoirement l’aube qui deviendra décor.

Bernard-Marie KOLTES, Roberto Zucco, Paris, Les Éditions de Minuit, 2001, p.127, 128.

[back to text]

Dissociation between the time of the performance and the time of its creation.

An actor’s performance, in the flesh, takes place in real time in theatre and film, even if we can intervene afterwards by editing. On a set or stage, the performance coincides with its perception or recording by a camera. In animation, on the other hand, it is generally a matter of deferred time, even if techniques such as motion capture [16] can produce a game in real time. The animator first designs and then develops the game [17]. There is a long time between conception and visualisation.

[16] This is a technique that links an actor to a digital form by means of a sensor device, enabling the actor’s movements to be transmitted to the form in real time. This movement can also be amplified or slowed down by algorithms.

[17] Seamus Gulhane suggests that cartoonists should quickly conceive and draw the game in rough continuity, finding gestures, postures and tempo, and then return to it to refine it… Seamus GULHANE, Animation: From Script to Screen, op. cit.

[back to text]

The possibility of collaborative acting within a character.

In film and theatre, a character is played by a single actor. In animation this is possible, but not exclusive, with several people often involved in the same game: a team defines compositions and movements, an animator sketches out actions and postures, assistants take care of secondary actions (movements of clothes, hair, intermediate drawings) and still others refine and clean up the drawings. Although one person is in charge of the game, everyone involved leaves their mark.

In ‘motion capture’ techniques, the distribution may be different, with one animator taking care of the body, another of the facial expressions…

In Paul Bush‘s film Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde(2001), each role is played by two actors who alternate frame by frame in identical trajectories, executing the same gestures. The result is a hybrid actor, vibrant for each role.

Finally, as far as the voice is concerned, the animator and the interpreter of a character’s voice are rarely the same.

As we can see from all these dissociations, acting in animation tends to distance itself more from reality than acting in film or theatre.

Identification – distancing.

We have seen that acting in the flesh corresponds to a metaphor through the literal (the literalness of the body in theatre, the literalness of the moving image of the body in film) whereas acting in animation deals directly with metaphor. We have also seen that to distinguish between reality and play, we need to understand the intention behind an action. So it’s interesting to note that part of the game’s approach requires the complicity of the spectator, who projects his ideas and attributes intentions. Whether performed by a real or animated actor, acting implies a closeness between actor, character and spectator, a relationship that is not always identical: between the fusional identification taught by Stanislavski [18] and the critical distancing dear to Berthold Brecht [19], several degrees of closeness are established. Stanislavski’s approach flirts with the literal by trying to identify actor, spectator and character. It seeks to detach itself from reality in order to incarnate itself in the character. Brecht demands a constant effort to avoid abandoning himself to daydreaming. He did not want to become incarnate and ‘relive’ the passion; he wanted to observe it from the outside while preserving his reasoning. He does not deny the metaphor, the mimetic displacement into a parallel world, but he has no confidence in the theatrical anaesthesia that awakens in catharsis. Faced with the hypnotic seduction of identification, the method of distancing seeks to keep both actor and spectator awake. Of course, identification is never complete and absolute but, in any play, there is a gap with reality, otherwise the play would disappear by becoming reality. Even in the cinema, we are never in total illusion and the simple fact of being on a theatre stage creates distance. In the same way, animated ‘actors’ are by nature more distanced than those in film, and it’s easier to identify with a real character than with a drawing. However, we identify more with actions than with images. So, as McLaren points out, you can make a matchstick man happy or sad, just by his movements [20], and effectively identify with his joy or sadness.

[18] Constantin STANISLAVSKI, La Formation de l’acteur, Paris, Payot, 1998.

[19] Bertolt BRECHT, L’Art du comédien : écrits sur le théâtre, L’Arche, 1999.

[20] Norman MCLAREN, lettre à l’auteur, quoted by Georges SIFIANOS, Esthétique du cinéma d’animation, Paris, Le Cerf-Corlet, 2012, p.20.

[back to text]

A few examples:

There are many examples of distancing in animated films, both in the context and in the acting. Here are a few examples.

In his film Neighbours(1952), Norman McLaren created distancing through the unusual movement of the real actors, filmed frame by frame, levitating to express their joy or sliding along the ground. He also uses the reduced scale of the sets, which become pictograms or symbols of settings, rather than functional houses. But apart from animating real people, other animation techniques offer their share of examples:

at the end of the animated cartoon Popeye the Sailor in Goonland (1938) by Fleischer brothers, following a fight, the film tears and the drawn characters fall into the chasm caused by the tear or try to cling to the film. Like a Deus ex machina, live-action hands intervene to glue the film back together. At the same time, the soundtrack plays the whistling of spectators calling for the projection to continue. Here the distancing comes more from the context, the characters simply reacting to the event outside their world.

Similar games can be found in Tex Avery’s Lucky Ducky(1948), where the characters reach the ‘limits of Technicolor’.

In the film Brocken down film (1985), Osamu Tezuka created a number of gags based on the process of running a film through the projector and the shift in the frame that sometimes occurs when the film jams or when dust collects in front of the projector window.

In this film, a character gradually climbs the photograms whose dividing line is shifted in the middle of the frame because of such a ‘mechanical problem’. Subsequently, as each of the two characters chasing each other is in half of a different frame, they pretend not to see each other, developing a dramatic game based on this discovery. Here the unveiling of the projection technique illustrates the distance theorised by Brecht.

Finally, we achieve distancing through the use of graphic games interacting with the characters, as in many of Felix the Cat‘s films: the shapes of the drawings change their meaning depending on how they are used. In the film Roméo and Juliette (1927) by Otto Messmer and Pat Sullivan, for example, the smoke from the exhaust pipe of a moped becomes a bouquet of flowers, the conical roofs of two castle towers become ice cream cones and the clouds nearby become the ice cream for the cones.

Felix’s tail, detached from his body and attached to a drawn heart (which had appeared to signify Felix’s love for his beloved) is transformed into a kind of banjo that Felix plays while singing… Here we have a game of drawn characters interacting with ‘graphic puns’.

In the variation of this particular state of mind of dramatic play in animation, we can note some behaviours that are as expressive as they are paradoxical: a gag used several times shows a character who continues to walk in the void for a reason, such as an excess of momentum for example, without falling. He only falls when he realises his situation. In the film Ready, Set, Zoom! (1955) by Chuck (Charles) Jones, for example, the coyote looks at the viewer and waves goodbye with his hand before falling.

In a similar way, we find a game that expresses a character’s thoughts rather than showing his action. In the film Andrei Svislotsky(1991) by Igor Kovalyov, it is the paper that meets the hand that tries to pick it up, rather than the other way round.

In Caroline Leaf ‘s La Rue (1976) we find another example that shows a state of mind through a gesture impossible to perform through any other medium: the dying grandmother tries to kiss her grandson, but he doesn’t want to. The boy’s desire to escape is manifested by his left arm slipping out and becoming his right arm before freeing itself from the grandmother’s grasp.

B : In search of a typology

If we want to go further and sketch out a typology of acting in animation, we need to untangle a web of combinations that are constantly diversifying.

Acting in animation is based on two pillars, plastic form and movement, and these two expressions can work together or contradict each other. On this basis, we can distinguish two polarities: a graphic game involving movement and a psychological game involving above all the manifestation of an intention. Thus, a range of factors can condition acting. We will try to identify them.

Acting – movement dictated by technique.

The technique and materials used can influence acting by dictating movements and characteristics. As animation techniques are numerous and constantly evolving, we will only give a few examples. The use of modelling clay induces transformations that introduce the feeling of the fluidity of an active material… as in Joan C. Gratz‘s film Mona Lisa descending a staircase(1992), in which transformations link the paintings of Van Gogh, Gauguin, Munch, Matisse, and so on. Here we have graphic evolution rather than acting, but in cases like Will Vinton‘s The Great Cognito (1982), successive transformations are part of the game. This film features an impersonator, and the transformation of modelling clay offers a relevant means of visually interpreting an acting style that could be described as literal pantomime, since this pantomime not only imitates a character but actually performs it.

The paper-cut technique imposes a two-dimensional approach, preventing any in-depth action. The resulting experience is one of deprivation, caused by rules that frustrate, an abstraction that creates distance. The emphasis on joints also provokes a feeling of stiffness. The bodies bend but do not twist, a stylisation we see in films such as Les escargots (1965) de René Laloux or La Demoiselle et le Violoncelliste (1965) by Jean-François Laguionie.

In La faim (1974) by Peter Foldès, one of the first films to use digital technology, the lines of one figure are systematically broken down to make up the next figure. This is what moves the figures away from anthropomorphism, reducing them to graphic expressions, creating a distanced game.

This film features an impersonator, and the transformation of modelling clay offers a relevant means of visually interpreting an acting style that could be described as literal pantomime, since this pantomime not only imitates a character but actually performs it.

Another form of influence of digital technology on acting comes from the ease with which 3D computer-generated images can be designed, which places the reference to gravity at the centre of a volume. In this way, the characters cushion their jumps or walks at navel level rather than on contact with the ground. This use of technique creates a paradoxical relationship with gravity, a mannerism of weightless movement. Observed, for example, in certain episodes of the series Télétubbies (1997)…

Other digital techniques are characterised by abrupt changes in the direction of the characters. In films based on video games, the ‘Machinima’, these expressions create a feeling of mechanical action, far removed from human mobility, as in Jim Munroe‘s My trip to liberty city (2003). We can observe a similar effect of mechanisation through the systematic braking of key images in certain early digital films, such as Si seulement (1987) by Marc Aubry.

This way of moving, due to the imperfection of the algorithms of the time, attracts attention and provokes the strong feeling of an imposed stylistic rule creating an affective distance for the characters’ play.

By the same token, we can talk about the consequences of traditional techniques, such as puppet films, where the reduction in scale provokes a feeling of childish awkwardness in the characters’ performance.

Acting dictated by a style of movement.

Over the course of its evolution, animated film has developed different styles of movement that condition the way its characters act. The industry in particular has adopted particular forms that have become established over long periods of time. The ‘rubber hose’ style of cartooning used long, black shapes without precise joints, giving undulating movements to the arms and legs of human and animal figures. These forms, which easily overcame gravity, marked the first decades of cartooning, creating a set of stereotyped characters, as in Hook and lader hokum(1933) by Studios Van Beuren, using both personality-related behaviour and graphic deformations.

Another choice made by the industry was the graphic evolution of the characters, who went from being wiry to egg-shaped, a graphic evolution accompanied by an adaptation of the movement, which became bouncy elastic. The bending-deformation of the hose-like shapes is replaced by the compression-stretching of the new shapes with the elasticity of a rubber ball. This style of movement, known as the ‘O’ style, has undergone different degrees of deformation linked to an evolving typology of play: from the measured deformations of Disney’s Ugly Duckling (1939), Le Vilain Petit Canard (1939) by Disney, to the accentuated deformations of the Tom and Jerry series, such as Hanna Barbera / MGM’s A Mouse in the house (1947) and the exaggerated deformations, which became visual gags, of Tex Avery‘sLe Petit Chaperon rural (1949).

Close to a naturalistic game with theatrical emphasis in the first case, we move on to a game emphasising the energy of the characters in the second, which uses chases as the main motive for the actions. In Tex Avery, the exaggeration of movement reaches an exceptional degree, transforming itself into a graphic game, momentarily dislocating the figures or exaggerating the size of certain body parts, such as the wolf’s bulging eyes, which reach the size of his body… In Tex Avery’s work, we have a game that sometimes corresponds to a personality type (the catatonic Droopy, the lecherous wolf…) mixed with a game of graphic forms, developed in the films of Felix the Cat, but in their own characteristic way.

In the wake of these major trends in games, marked by industrial choices or the influence of figures such as Tex Avery, or by the advent of television and the need to produce quickly and in quantity, as well as by changes in public preferences, the forms of games evolved. Speech largely replaced action in television series (ironically called ‘illustrated radio’) and animation became ‘limited’. Movements became schematic, and the psychology of the game – which was already given little prominence – gave way to narratives conveyed by character-types who tirelessly carried out the same actions, as in Road Runner, a series of cartoons by Chuck Jones published in 1949.

In a move towards minimalism, both graphically and in terms of mobility, we find the character-signs, developed in particular by the Zagreb school, as in Vatroslav Mimica‘s L’inspecteur rentre chez lui (The Inspector Goes Home) (1959),

or Waou-waou (1964) by Boris Kolar.

After these periods marked by stylistic assertions, recent choices are characterised by the coexistence of styles ranging from naturalism to extreme minimalism. This development is largely due to the advent of digital technology, which encourages hybridisation, but also to the proliferation of auteur films.

Anthropomorphism and acting

Extending the spirit of fairy tales, this approach has left its mark on a whole area of animated film. In line with animation’s ‘magical’ ability to ‘bring to life’ the non-living, anthropomorphism, this fundamental human approach, has found fertile ground. In its expressions, we can distinguish two attitudes: literal anthropomorphism and evocative anthropomorphism.

Literal anthropomorphism adopts an explicit, illustrative approach, taking advantage of similarities between objects and the human figure, such as car headlights and eyes. However, these similarities are often completely arbitrary, leading to prostheses being pushed into inappropriate shapes. The arms of the water-carrying broomsticks in the Sorcerer’s Apprentice sequence in Disney’s Fantasia (1940) are a typical example. Another example can be seen in Tex Avery’s Little Johnny Jet (1952), where planes behave like humans even though their shape is inappropriate. In this film, two propeller-driven planes act like a couple with their ‘baby jet’. A forced anthropomorphic game, tipping over into kitsch.

In evocative anthropomorphism, the manifestations of a personality come through movement or context, independently or with little modification of form, as in McLaren‘s Rythmetic.

A typical example is McLaren’s Il était une chaise (1957) (à partir de 7.14’), where the form remains intact and the positions are exploited from different angles. In this pantomime, only the movements and postures of the chair evoke a personality and intentions (admirable is the moment when it is placed diagonally, on its ‘knees’ and ‘head’, with all four feet in the air, and when it discreetly lifts one of its supports to ‘look out of the corner of its eye’). The same logic is adopted by the two desk lamps in John Lasseter’s film Luxo Jr (1986).

However, while in this film the action is autonomous and comprehensible, in McLaren’s film we only attribute intentions to the elementary movements of the chair thanks to the reactions of actor Claude Jutra. We see a similar implication of context in another McLaren film, Discours de bienvenue (1960), where the microphone reacts to the actions of the actor McLaren.

From the arbitrary distortion of literal anthropomorphism to the limited distortions of Rythmetic, from the smugness of Luxo Jr’s interpretation of the two lamps to the essential interaction with an actor to give meaning to the reactions of the anthropomorphised objects, we see the existence of nuances that give the acting a different and unequal value each time.

Choreographed acting, inventive acting

One of the particularities of animated cinema is that it conceives the movement it attributes to its forms. We might have expected a much more choreographic approach to the forms on offer. This is clearly not the case, probably because of the spontaneous tendency to imitate reality. Nevertheless, in the films that use choreographed movements, two tendencies can be distinguished: one chooses to show characters dancing, as in Jean-Charles Mbotti Malolo‘s Le Sens du toucher (2014), the other attempts to invent an original mobility, appropriate to the subject and its plastic form. Several of the films we have mentioned (McLaren’s Neighbours, Chris Hinton’s Flux (2002), …) go in the second direction. Nevertheless, it seems to us that the dramatic game of applying an appropriate movement to each form is far from having exhausted its potential.

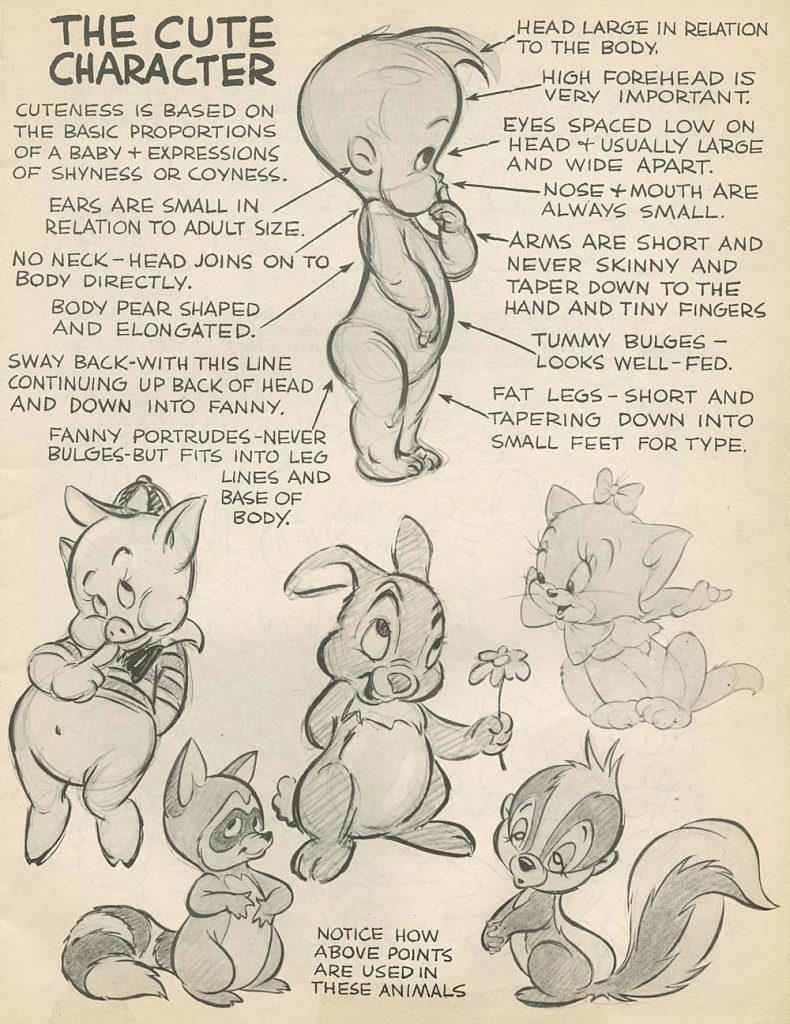

Throughout the history of acting in animation and the stylistic evolution of the forms, we see a tendency to invent a movement to characterise a personality [21] and another that uses a standard ‘style’ of movement such as the ‘O’ style or the ‘hosepipe’, already mentioned, to interpret several roles [22]. As in Comédia del Arte, in this case we have character-types rather than individual psychology.

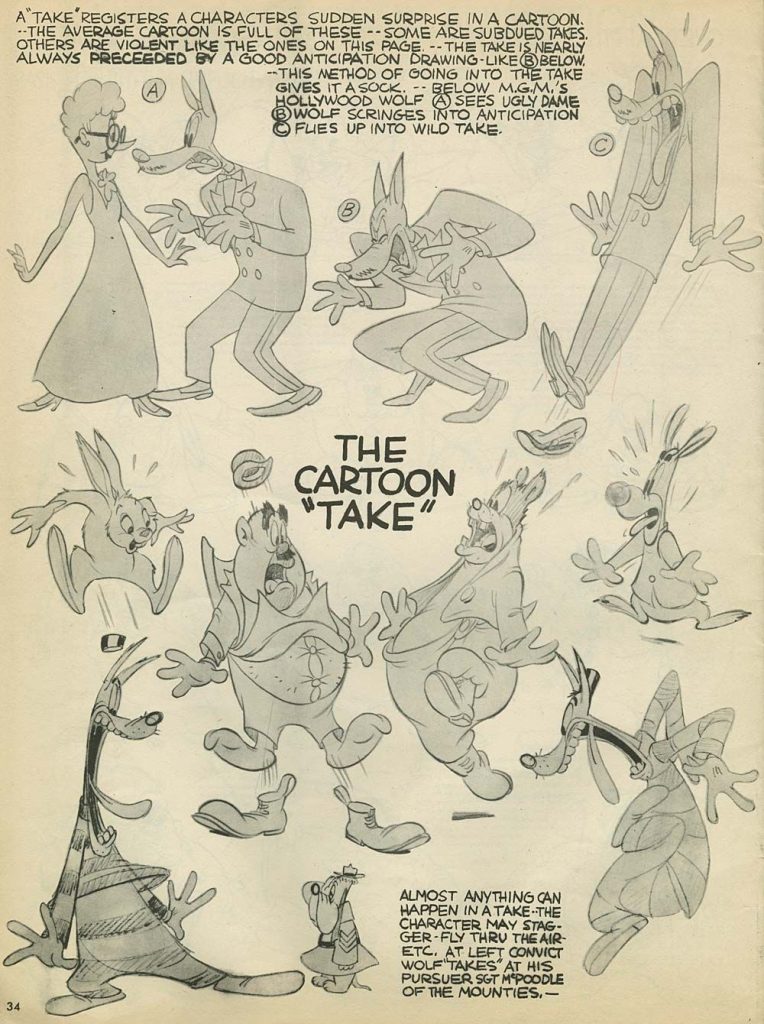

This typology of acting has not failed to develop stereotypes and mannerisms, and some of the formulas used have become canonical through repetition. Several examples can be found in fundamental cartoon manuals, such as Praiston Blair‘s [23]: the scary ‘take’,

the ‘cute’ attitude,

and the systematic anticipation of the slightest action are all part of this.

In other cases, the animators were more inventive (at least initially), as in Panique au village (2009) by Stéphane Aubier and Vincent Patar, who developed a game inspired by the movements of children handling small figurines. These authors ended up creating their own stylisation by systematically using this game. In Carles Porta Garcia‘s François le Vaillant (2001) we also find a game reminiscent of children’s gestures, accompanied by vocalisations and sound effects.

Aside from Karen Kelly‘s Egoli (1989)

and the aforementioned L’inspecteur rentre chez lui (The Inspector Goes Home), Michal Socha‘s film Chick (2008) is a typical example of the search for a balance between graphics and movement to express a personality.

This short film is exemplary in this sense, since each figure graphically expresses a personality and is associated with an original and expressive movement in the same direction.

[21] A type of movement (stylised, exaggerated, limited, etc.) will be appropriate for a particular personality. A character can adopt and identify with a movement, like the squirrel and his hysterical gait in Chris Wedge’s Ice Age (2002).

[22] This approach is not just industrial. Whether it’s a knight, a princess, a couple having dinner or a tramp retrieving an old box from the bin, Paul Driessen always uses the same ‘style’ of fluid, vibrant movement as a personal signature.

[23] Preston BLAIR, Cartoon animation, California, Walter Foster Publishing, reissue 1994.

Also ine Richard WILLIAMS, The Animator’s Survival Kit, op. cit.

[back to text]

Acting conditioned by the dynamics of actions

Apart from techniques and the historical evolution of forms, if we examine the dynamics and accents used for actions, we can group animation play according to a small number of approaches.

Acting through regular progression: this play is characterised by a movement that makes all the details of the shape evolve in a homogeneous cadence. Rotoscoping can produce this type of movement, which can already be seen in the film Les Voyages de Gulliver (1939) by the Fleischer brothers.

A similar effect, achieved by a drawing evolving with a homogeneous dynamic, can be found in animated films by Bruce Bickfort [24].

The ‘morphing’ technique can also provoke actions characterised by a homogeneous cadence. Then, it is a fast or slow rhythm that will add or take away the dynamics of this type of expression.

Anticipatory acting: following the canonical principles of cartooning presented by Preston Blair [25], the emphasis is on preparation rather than action, contributing to highly dynamic play. The classic era of North American cartooning perfected this approach. It is used, for example, in the Hanna-Barbera Tom et Jerry series (Tom & Jerry – Kitty Foiled (1948).

This approach evolved, showing the anticipation of the action and then ‘erasing’ the characters in a form of kinetic blur of high speed, as in the Road Runner films.

[24] In the documentary Monster Road (2008) by Brett Ingram.

[25] Preston BLAIR, Cartoon animation, op. cit.

[back to text]

Acting using the statement: the opposite approach consists of marking the finishing positions rather than the preparation of an action. In this less common approach, you arrive at the result without bothering to prepare the action, which always comes as a slight surprise. We find this type of action in the films of Yuri Norstein, such as The Héron and the Stork (1974) ou encore dans les animations de Lotte Reiniger.

Acting with unpredictable changes

We have already mentioned a movement that surprises by using sudden changes. This mannered, mechanical movement is used in video games in particular, in a graphic rather than psychological game, and designates rather than interprets a personality that disappears in favour of the action. This game is typical of the ‘Machinima’ mentioned above, films that borrow their material from video games.

This movement, which characterises three-dimensional characters evolving in an equally three-dimensional space, follows on from the so-called ‘limited’ forms of animation of the television era or the minimalism of the Zagreb school.

Use of ellipses, or the evocation of movement: this is a particular form of representation of action that is specific to animation. This movement provokes ‘resonances’ by interrupting itself and leaving its completion to the viewer’s imagination. McLaren‘s Blinkity Blank (1955), is an early demonstration of this approach, which is also used at length in Sébastien Laudenbach‘s recent film La Jeune Fille sans mains (2017). Here we could speak of an impressionist approach to movement.

Other variations on an elliptical game exist: in Paul Driessen‘s film David (1977), the cries of a character who is supposed to be tiny invite the viewer to see a movement (which does not exist).

In Garri Bardine‘s film Banquet (1986), the movement of dishes on a banquet table, accompanied by voices, evokes the actions of invisible guests… In Caroline Leaf‘s film Entre deux sœurs (1991), the visible parts of the figures evoke the invisible parts. In Dragic‘s Le jour où j’ai cessé de fumer (1982), the action also serves to reveal the set, which appears in cut-out as soon as a figure passes behind an object.

Acting that uses graphic pantomime is a separate category. We’ve already mentioned this approach in the films of Felix the Cat, which use graphic punctuation marks such as (?), (!), (…) as props for acting. In this game, a question mark (?) becomes a fishing hook because of its similar shape, and the character immediately uses it to fish. In other cases too, it is always the equivocation of the drawing that creates the graphic pantomime: the outline of a puddle becomes a lasso rope…

In another form of graphic pantomime, we have the transformation of a sign into a character: in McLaren‘s film Dollar Danse (1943), signs are transformed into anthropomorphic figures by their mobility. These characters can dance or, as in Rythmetic, even take on the traits of a developed personality. In this example, we can describe the behaviour of certain figures as mischievous.

Priit Pärn also uses graphic games to play with the ambiguity of forms. In Time out (1984), the horizon is transformed into a line of waves, which are in turn transformed into a clock, and the ‘V’ of a seagull is used for its hands. Developing his narrative through the association of ideas and shapes, the characters’ game consists of interacting with the many surrealistic transformations. As in a dream, the resemblance of shapes takes us from one place to another, taking the characters through different situations.

Naturally, all these methods can be combined, with graphic pantomime using anticipation and so on.

Forms of play according to the major trends in art history

If we examine the production of animated films and the major movements in the history of art, we find that there are games characterised by the adoption of similar approaches. These approaches do not coincide chronologically with art movements, animation being a young art, but are borrowed as stylistic expressions a posteriori. Without being exhaustive, we can mention a few examples.

Naturalistic acting: often the result of ‘transferring’ images from a film using a ‘rotoscoping’ device, as in Gulliver’s Travels already mentioned, or using a ‘motion capture’ device, an equivalent of casting for movement, which enables the movement of a real actor to be transmitted to a digital form. The quality of the dramatic interpretation in this case depends on the plastic aspect of the form in question, which may or may not be conducive to this type of performance. According to the testimonies of actors who have used this method, the result seems less dynamic than reality and the performance needs to be amplified, which is what the technique allows.

Traditional approaches to drawing have also sought to remain close to reality through a naturalistic movement, with uneven results. One of the oldest animated films in this category is McCay‘s The Sinking of Lusitania (1918) de McCay, but there are also recent films such as Takahata‘s Grave of the Fireflies (1988).

Another approach that can be described as interpretative naturalism was initiated by Ray Fields, a teacher at Liverpool Polytechnic in the 1980s, creating a veritable school of thought. In this approach, the graphics are free and the game is based on the observation of nature from notes and quick sketches taken on the spot. The postures, situations, contexts and rhythms observed are internalised before being rendered by the animation, and the urgency of these sketches could sometimes introduce expressionist distortions. In the game that results from this practice, we see both details that bear witness to the observation of nature and the presence of the animator’s subjectivity, who spontaneously interprets this nature. There are few examples of this school: Thin Blue Lines (1982)et Carnival (1985) by Susan Young, Night club (1983) by Jonathan Hodgson and a few others.

In other cases of naturalistic acting, such as in Frédéric Back‘s L’Homme qui plantait des arbres (1987), a technique based on a succession of cross-fades creates a feeling of smoothness in the movements, which in turn conditions the acting. We have a naturalist movement applied to an impressionist graphic/texture.

In still other cases, the naturalism comes solely from the sound, as in John and Faith Hubley‘s

Moonbird (1959), based on direct recordings of children playing, or in films such as Nick Park’s Creature Conforts (1989).

Minimal acting: in this form of dramatic interpretation, the acting consists of indicating, evoking or symbolising the action. It often involves a moving pictogram, which may be mechanical and limited in its action or, on the contrary, highly expressive. Sometimes the image is minimalist, as in the film Waou-waou by Boris Kolar already mentioned, sometimes it is movement, as in Scarabus (1971) by Gérald Frydman or Concert (1962) by Walérian Borowczyk.

In the same category of acting, we also classify several ‘animated gifs’ or other ‘buttons’ on websites, or animated diagrams, arrows, dotted lines, flashing shapes, etc., sometimes with intentions that reflect a personality through anthropomorphisation. This minimalist style, with its characteristic abstraction and stylisation, is conducive to the expression of abstract ideas.

Expressionist acting: like theatre, but for different reasons, animated film often uses forms of exaggeration and, as a result, has affinities with expressionism. In theatre, the spectator’s distance from the stage imposes an amplification of the actor’s performance. In animated film, this exaggeration is often caricatured for comic purposes and concerns form, movement or both. We have seen that Tex Avery’s exaggeration of form can become a gag and that it is linked to expressionism in acting. In other films, the plastic form remains – relatively – discreet and the expressionism is mainly in the acting. This is the case with Joanna Queen‘s Girls Night Out (1987) or Jef Newit‘s Loves me, loves me not (1993).

We noted a different form of expressionism, using transformations, in Will Vinton’s The Great Cognito.

We can also find other uses of deformations, such as in Koji Yamamura‘s film A Country Doctor (2007), where their systematic use is part of a stylistic signature.

Cubist game: the principle of a ‘cubist’ game exploiting movement taken simultaneously from different points of view is indeed possible in animation, even if this form is probably not widely exploited. (The animated sequence based on Picasso‘s drawings by Wes Herschensohn in the film The Picasso Summer (1969) by Robert Sallin, Serge Bourguignon, does not take this route. It would be a question of a composition of different moments and angles of views selected and combined into a whole.

Nevertheless, we can consider as variants of a spirit that would be close to cubism films that alternate different spaces behind the action of a character as in Trepass (2013) by Paul Wenninger and Nik Hummer. Or Paul Bush’s films such as

Furniture Poetry (1999) in which several objects of the same kind – a piece of fruit, a table, a pot – alternate in a moving representation of the same objects. This play, mainly graphic, becomes significant in Paul Bush‘s Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, mentioned above.

Close to the attitude of cubism, which would examine an object simultaneously from different angles, we can consider films that explore the stroboscopic effect by making a parallel montage of different actions to the frame. This could involve Shen Jie‘s Horse (2013) ou son autre film Stammer (2013), or films by d’Augustin Gimel such as Fig. 4 (2004), in which bodies and movements are recomposed from pornographic images taken from the internet. In all these cases, the acting is graphic rather than psychological.

Impressionist play: the succession of drawings in a film automatically creates a vibrant texture, which would bring these films closer to Impressionism, at least in terms of the graphic effect of texture in motion. Some of Frédéric Back‘s films, such as Crac (1981) or L’homme qui plantait des arbres (1987) have a graphic style similar to that of the Impressionists. Others, such as Ron Tunis’s Le Vent

(1972) portray this sometimes strong and aggressive vibration through alternating warm and cold colours. This is also the case with Karen Kelly‘s Egoli, where the vibrations of the texture are a means of provoking strong sensations that accompany a subject dealing with violence. The deformations of the figures and the restlessness of the movements give it an expressionist character, but the rough nature of the drawings also gives it an impressionist approach. Generally speaking, this impressionistic approach could be found whenever rough observational sketching is used, as in the films of the Liverpool School. Nevertheless, in many cases it is difficult to draw a dividing line between impressionism and expressionism. This is the case with Chris Hinton‘s Flux, whose actions are animated freely in space and in a vibrant way, like fleeting impressions that follow one another, but whose cartoonish deformations also take them into expressionist territory. In a way, we can also describe a film like McLaren‘s Blinkity Blank, as impressionistic, at least in part, since the movement of its figures is the result of a composition that our brains work out from a few suggested images.

Surrealist acting: we would rather talk about surrealist worlds or actions than about play as such. Whether in films conceived by Surrealist personalities, such as Salvador Dalí’s Destino (2003), or in films representative of Surrealist schools such as Harpya (1979) by Raoul Servais of the Belgian school, or in numerous films by Jan Svankmajer of the Prague Surrealist cycle, Surrealism shares its forms of play with other movements in animated film. This play can be realistic, use transformations or be minimalist and jerky, as in Gérald Frydman’s Scarabus,

or even mix ‘styles’ of movement within a film. It is the dramatic universe and the paradoxical nature of the actions that qualifies them as surrealism rather than a specific game. In fact, animated films distance themselves from cinematographic photorealism either through the image or the movement, and their positioning beyond realism by their very definition leaves no exclusive place for sur-realism. Otherwise, we would have to place the whole of animated cinema in this domain.

We note that this attempt to list different kinds of dramatic play in animation can only be non-exhaustive. The number of possible combinations, based on numerous techniques, can only be limited by the imagination of the creators.

Like every language used in literature, animation has its limits, but fortunately the expressive potential is far from exhausted in both cases.

Georges Sifianos