ABOUT THE MISSTEPS OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

Conception issues in certain AI approaches

Georges Sifianos

We are currently seeing a craze for designing algorithms based on “prompts”, to the detriment of other approaches, particularly for image creation.

This method, which relies on verbal requests, is just one among many. When imposed on artistic creation, it causes confusion among creators, as they are given a tool that was not designed for them. This approach tends to alter practices, results, and, in the long term, the very essence of the creation it was supposed to serve. It is a tool that hastens the replacement of all creative results with a “ready-made” solution.

Artificial intelligence relies on methods that scientists learned during their studies and subsequently developed. As a result, a multitude of applications are emerging, but their initial vision is not always appropriate for all fields. The world of art does not operate using the same thought patterns as science. The differences between a sensitive approach and an intelligible approach are not insignificant. Can everything be described and organized with concepts or prompts? Concepts rationalize, but as Bergson says, “Conception is a last resort when perception is not possible, and reasoning is designed to fill in the gaps in perception or to extend its scope.” [1]. A concept is precise but reductive, while an artist’s intuitive feeling may prove more relevant, capable of capturing nuances and a global vision that might escape a conceptual approach.

A similar criticism can be levelled at the statistical approach, widely used by AI, which provides probabilities but often falls prey to bias. Election forecasts in different countries provide examples of the irrelevance of statistics, whose results incorporate errors. This margin, often negligible, can sometimes be absolutely significant, as in the case of elections that favor radical change, or decisions concerning war, for example. [2]

Engineers alone do not have the necessary culture to address this type of bias. They need the collaboration of specialists from all fields. It is essential to question the certainties of the omniscience of algorithm designers, who tend to apply the same models everywhere after having succeeded in certain areas.

[2] Henri Bergson, La Pensée et le mouvant, Presses Universitaires de France, 1938, p.145.

[2] This is the idea developed by Nassim Nicolas Taleb in his book The Black Swan, Random House Publishing Group; 2e édition, 2010.

A black swan is a highly improbable event with three principal characteristics: It is unpredictable; it carries a massive impact; and, after the fact, we concoct an explanation that makes it appear less random, and more predictable, than it was. For Nassim Nicholas Taleb, black swans underlie almost everything about our world, from the rise of religions to events in our own personal lives.

We can talk more specifically about different scenarios:

- The use of “prompts” to create images and videos.

- The use of “white noise” as a common denominator to transition from one image to another.

- The notion of “style”.

- We can also look at specific examples of algorithms going down the rabbit hole, such as those that attempted to translate videos into drawings or transform videos into animated paintings.

The use of “prompts”

The use of “prompts” to produce images and films, currently in vogue, accentuates the dependence of the sensible on the intelligible or the symbolic, which can be effective but also impoverishing. A word or phrase allows us to understand, but also reduces the richness of expression. Words, like prompts, are simplifications that, when combined, can represent a multitude of nuances. This representation is not analogical but symbolic, and it differs from one language to another.

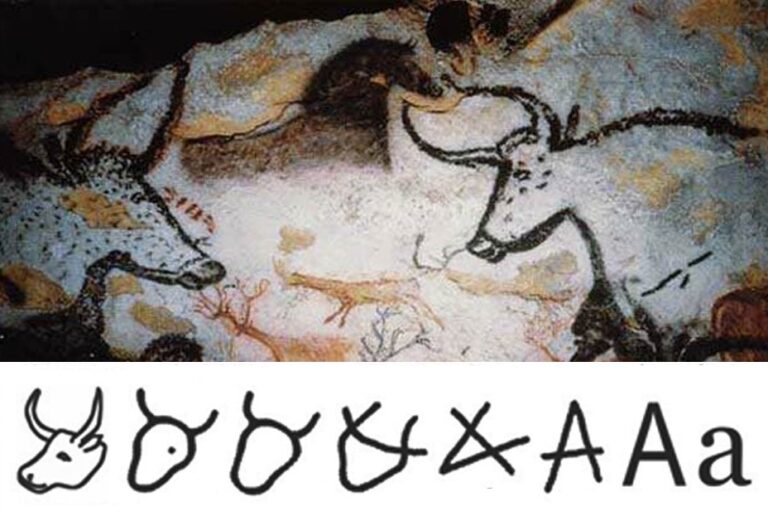

Writing was originally a form of painting, as evidenced by prehistoric cave paintings. By reducing it to pictograms, there was a significant loss of information. An “A,” for example, tells us nothing about a bovine, which was the origin of the Aleph. However, writing also allowed literature to spread and evolve. Loss in one area is actually a shift, a radical transformation.

If we ask the algorithm to generate “a tree,” we will get an image, but not necessarily the right one. For an algorithm, a tree is a statistical average of the trees known during its training. In this sense, the algorithm works in a similar way to language, where we strive to find the right combination of words to describe our feelings: it is different to say “a tree” and “a hundred-year-old plane tree,” or to define an object with greater precision.

In spoken language, a word triggers a process of imagination. The representation it offers is a structure that remains incomplete in its details; it is evoked, and its completion is unique to each individual. Despite this margin, Roland Barthes described language as “fascist” because it does not prohibit, but imposes the meaning that we will understand when using a particular word or syntax. [3] In comparison, the form proposed by the algorithm goes much further. It is complete and definitive. Proportionally speaking, creating images from prompts leaves much less room for our imagination than language does. Even though we are generally offered three variants that we can develop, the algorithm imposes its own touch each time and is always one step ahead of us. It is very difficult to guide the prompts to obtain something as we imagined it. We just have to follow along.

When reading a text, we enjoy giving free rein to our imagination, but when we discover the results of the prompts, we are always faced with surprises. Sometimes we are even fascinated by the performance of this mysterious “intelligence.” However, we do not experience the jubilation of a “eureka” moment, of an idea that belongs to us. With these images, we make discoveries, but our imagination is confiscated. The famous half of the work that is created by the viewer shrinks like a shrunken skin.

[3] «Language is neither reactionary nor progressive; it is quite simply fascist; for fascism does not prevent speech, it compels speech.», Roland Barthes, Leçon, Paris, Seuil, 1978, p. 14.

In cinema, in live-action filming, we observe a similar phenomenon: the raw material is copied from nature. We are fascinated by the train arriving at La Ciotat station or by the wisps of smoke in the Lumière brothers’ films, but this fascination is not an external domination, because we are part of this reproduced nature. Our experience recognizes this world as being objectively copied.

In an artifact such as a drawing, an adult recognizes the trace of a creator behind the result. Our fascination in this case comes from the performance, the tour de force of one of our fellow human beings, and therefore potentially of ourselves. Of course, there are variations and hybridizations of images where we are unable to sense the human or technical origin of the proposed result. But the essential point is that our emotion, our appreciation of a work, is conditioned by this familiarity or strangeness we feel when faced with the proposed work.

Artistic beauty, natural beauty, “automatic” beauty?

In aesthetic appreciation, there has long been a fundamental distinction between “natural beauty” and “artistic beauty.” [4]

Since the advent of artificial intelligence, a third category has sought to slip in and assert itself between the two: something that could be described as “automatic beauty,” which lies halfway between the intentional and the unintentional, the subjective and the objective. These are works created by algorithms, particularly artificial intelligence algorithms.

These works are “directed” by “prompts,” i.e., summary phrases describing what is being sought. However, control over the results is fairly rudimentary. The algorithm and its database largely determine the final result. It is not “natural,” as the process is the result of human activity, but it is not an artifact either, insofar as the result is automatic, largely beyond our control, and unpredictable.

[4] Hegel, Esthétique, Paris, Flammarion, 1979, vol.1, p. 10.

The fascination it exerts comes from surprise. It is not a performance or a feat of skill that provokes emotion in an artifact. It is not the recognition of an “objective” representation of our environment. It is an “in-between,” a third scenario. The representation can take the form of a photograph, naturalistic, objective, or in the form of an artifact, evidence of human creation. Nevertheless, we know, since we saw it emerge from a verbal command, that it is neither a work of art nor a reproduction of nature.

Ethics

With AI, the raw material is copied from a database of universal image production. Filtered through cultural filters, AI content is dominated by the databases on which the algorithms have been trained. If the medium has always spoken, according to McLuhan’s theory [5] , the medium of algorithms and AI tends to impose itself even more. The algorithm imposes itself as a co-author.

An important question then arises: how do we choose the criteria and content of the databases for training algorithms? This question should not be taken lightly. One could argue that there is no choice, and that database material is “objective” in this way. But is this really the case? Everything that is somewhere is there for a reason. Chance is conditioned in one way or another; it is the result of contextual conditions, conditions that precede it.

Just as there is academic ethics for researchers, there should be similar ethics and requirements for objectivity and quality in the education of algorithms. Why would engineers trained at the world’s leading universities allow algorithms to be trained in an improvised manner, like amateurs?

When we delegate choices to algorithms, which will determine our universe as if it were objective nature, shouldn’t we pay more attention to the content of the databases in which they are trained? Shouldn’t we create databases with the same ethical standards as those found in academia and research?

In other words, instead of letting algorithms “graze” freely in databases, shouldn’t we offer them “ethical vectors” from the best universities, such as Stanford, which has produced many engineers?

[5] Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media, McGraw-Hill, Columbus, Ohio, U.S., 1964.

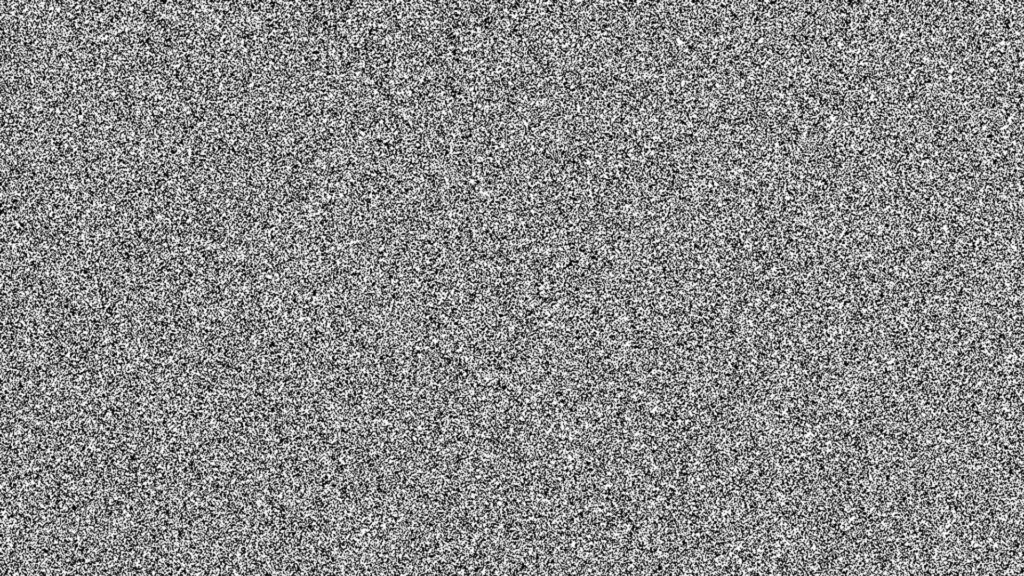

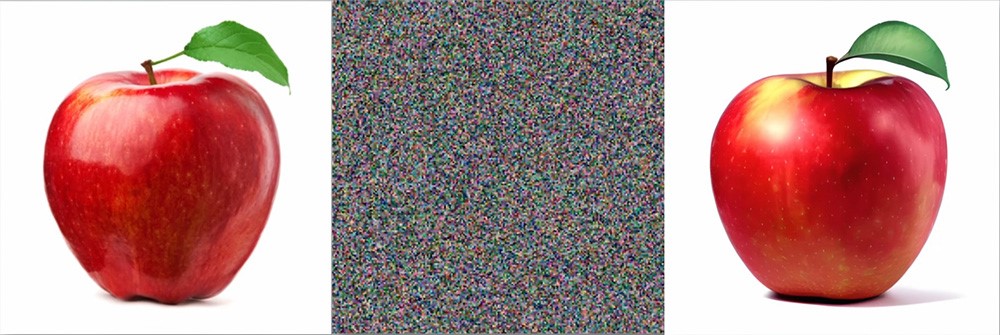

The fragmentation of white noise

Many artificial intelligence algorithms, particularly those involving images, use “white noise” as a common denominator. In other words, they gradually reduce an image to a neutral representation, composed of black and white pixels distributed evenly, randomly, and in equal quantities across a surface.

Then, proceeding in reverse, the algorithm, guided by an objective (via a prompt, for example), seeks to compose an image with similar formal characteristics.

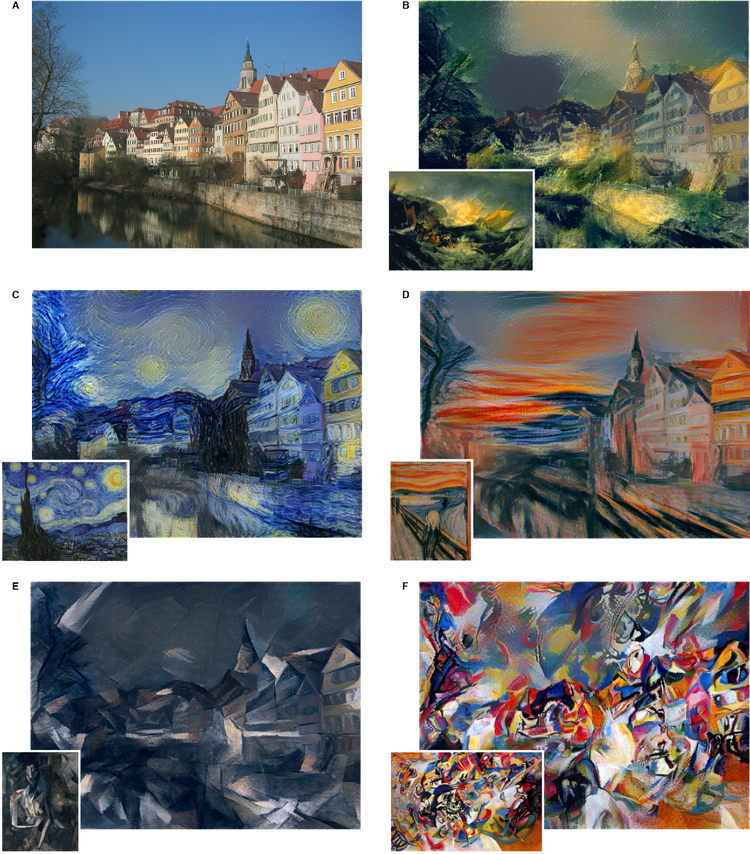

This process can be interpreted as the “style” of a painting, which has itself been reduced to white noise. The algorithm attempts to ‘dream’ this image in the same way that we distinguish shapes in clouds. Thus, we can obtain a photo translated into the “style” of Van Gogh, Gauguin, Modigliani, etc.

However, this method, which involves fragmentation, selects certain things and discards others. For example, the wood chips used to make chipboard are still wood. However, chipboard has lost all trace of the history of the tree that provided the chips. A plank, on the other hand, continues to live. The “vectors” that created the tree continue to exist in it. The plank reacts to humidity and moves. It tells the story of the tree, from the moment it grew its branches (the knots on its surface) to the storms that broke some of them, to the dry or humid climate that formed more or less tight rings in its trunk, etc.

As humans, with a birth, a life, and an inevitable but dreaded end, the metaphorical testimony of the tree’s life is capable of moving us because it resembles us. It tells us our own story.

In nature, morphogenesis follows laws that generate prototypes, which are then broken down into numerous variations of forms. Quadrupedalism, the division into head, thorax, and abdomen for insects, symmetry, the structure of roots, trunk, branches, and leaves, etc., are manifestations of this process. Earth’s gravity is largely responsible for these structures.

Our emotions are also based on similar conditioning, related to our lived experience. Our real life is supported by a metaphorical universe.

Thus, size awakens emotions in us that differ depending on a comparison with our own scale. Beyond a certain threshold, all dimensions are indistinguishable in terms of aesthetic appreciation; they belong to the same order of magnitude. For example, a distance of 40 billion light-years and another of 350 billion light-years make no noticeable difference to our aesthetic appreciation. Both belong to the category of the immense.

On the other hand, the height of a cathedral compared to that of a house, where you can almost touch the ceiling, creates very different sensations. Using the same logic, we can see that:

° A horizontal line is associated with rest, unlike a vertical line or the unstable dynamics of a diagonal, which is perceived as being in motion.

° Distance puts our emotions into perspective. Seeing a dead stranger in front of you does not have the same emotional impact as if the dead person were a few houses away, or if the event took place in a distant country. (Who knows the exact number, to within one person, of those who have drowned in the Mediterranean?)

° The passage of time changes our emotions. A tragic event loses its intensity over time. Similarly, when we see a shape or a painting that we like every day, we eventually stop noticing it.

° The colored atmosphere of a room or its temperature changes our emotional appreciation.

° Our physical conditions, such as being hungry, sleep deprived, feeling safe or under the stress of an emergency, being relaxed or under pressure, radically influence our assessments, reasoning, and emotions.

° The cycle of day and night, our heartbeat, etc., discreetly impose themselves and condition our assessments.

° Not to mention the cultural influences that largely determine our emotional responses.

° Finally, we can mention our habits and the familiarity we acquire from birth. We become attached to the place where we were born, even if it is the driest desert or the coldest country in the far north.

We learn by imitating, and any form that represents our experiences, in one way or another, attracts our attention and emotions. Art takes advantage of this capacity for metaphorical evocation of materials. By fragmenting the wood, this memory disappears; chipboard renders the wood amnesiac. The testimony of its life disappears forever. Walter Benjamin spoke of the loss of “aura” through the process of industrial reproduction. If the algorithm is not trained in the morphogenesis of the history of images, its proposals will always be agglomerates rather than original creations. We will always have creations, but they will have lost their connection with the profound reason that gave rise to them.

Algorithms that use the fragmentation of “white noise” erase history, raison d’être, and the roots of forms in their historical context. They inevitably lead to a culture of appearances, a mannerist culture, a culture of pretense and “style.”

Style:

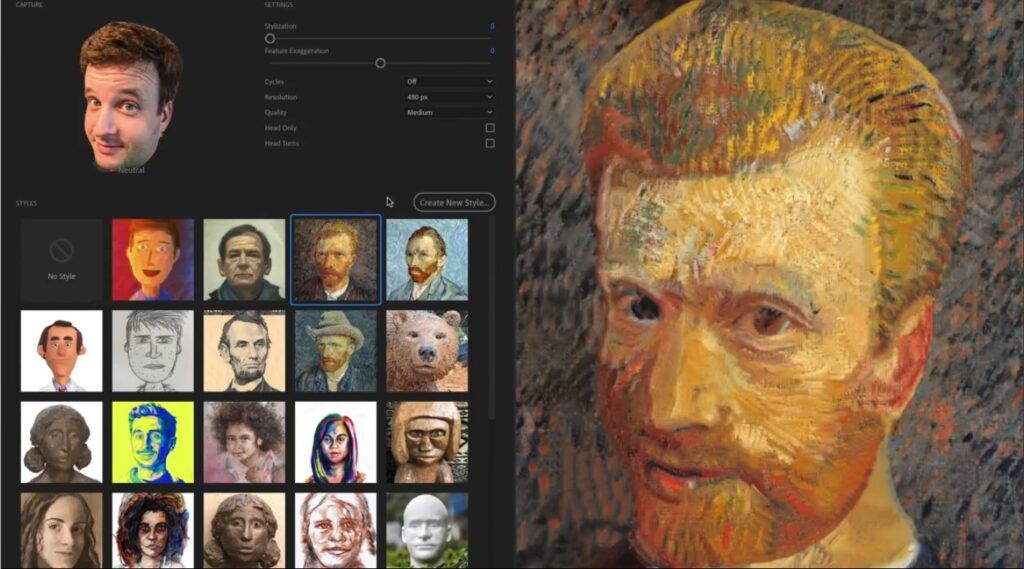

Artificial intelligence engineers are already working on the idea of reproducing a particular style (the Van Gogh “style,” the watercolor “style,” etc.) [6]

This reflects a cultural flaw in their education, which is scientific but insufficiently artistic. They approach artistic representations superficially, focusing on their appearance, their “style.”

However, style is a consequence, the result of a creative process that emerges without being planned. Style is, in principle, the culmination of a creative effort. It is not an end in itself. Style reflects the context, sources, and conditions that gave rise to it. For example, the belief that material life has no value compared to spiritual and eternal life gave rise to dematerialized, flat, Byzantine painting, unlike Renaissance painting, which placed the viewer, the human being, at the center and rediscovered perspective and the materiality of volume.

[6] A Neural Algorithm of Artistic Style, Leon A. Gatys, Alexander S. Ecker, Matthias Bethge. arXiv:1508.06576v2 [cs.CV] 2 Sep 2015. arxiv.org/pdf/1508.06576

If style becomes an objective, the work is doomed to fall into the trap of mannerism. Mannerism does not look at the world beyond its surface. It is a superficial view of a creator who, for lack of anything better, places himself at the center of the world. In this case, style resonates with individualism.

Is there an alternative path?

Certainly, if the design of algorithms sought to integrate vectors, the testimonies of history and the genesis of each form. The fact that the water molecules carrying the color pigments in a watercolor, for example, spread according to the facilities or constraints imposed by the grains of the paper. This information about the evolution of a journey is not superficial. It is the story of this journey, revealed by the materials, that speaks to us and touches us emotionally. Of course, there are other levels that testify to the knowledge, sensitivity, skill or clumsiness, effort or lack of effort of the artist. All these testimonies must be taken into account. The concept of “style” is merely an impoverishing reduction.

Algorithms are generally designed by computer engineers, who have had little education in certain areas, particularly culture, aesthetics, and aspects of sensitivity in general. Their training is based on reasoning rather than on the development of sensitivity. The strengths and weaknesses of this education are naturally reflected in their algorithms.

In addition to the “style” design we just mentioned, there are two other examples: the first concerns Adobe Character Animator CC and one of its features, which was promoted in 2017 but has since been marginalized within the software.

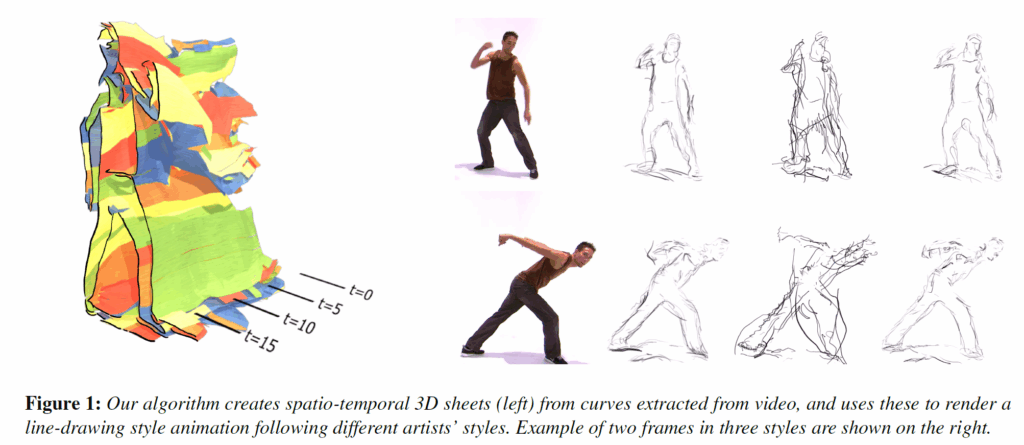

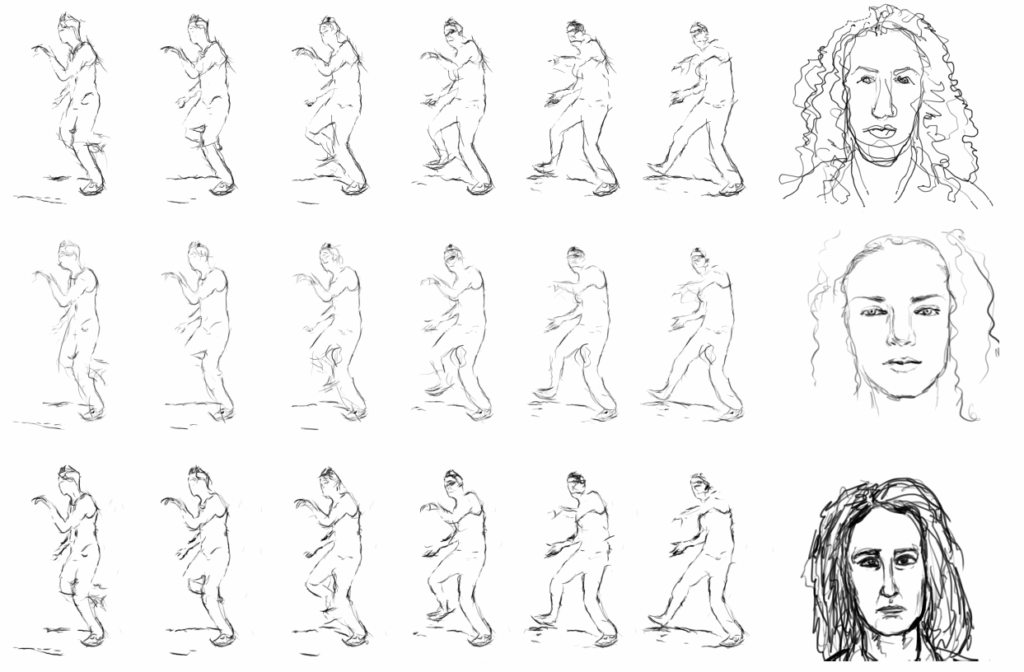

The second example is a 2015 attempt (now abandoned?) to translate videos into cartoons, according to the “style” of different cartoonists.

Artificial intelligence is capable of imitating and transposing shapes and movements. This means that a person’s figure can be made to move and speak in the form and manner of another person. (Donald Trump can be transformed into Putin and vice versa, to update the examples using Obama and the Pope…).

Adobe’s Character Animator algorithm is capable of translating your face, captured by a webcam, into an animated painting that matches a model you have submitted. This plastic translation can evolve by reproducing your movements. [7]

However, looking at the result, one does not get the impression of an animated painting, but rather a face with naturalistic proportions on which paint has been applied.

Bastien Dubois, Portraits de Voyages, Sacrebleu, TV series, 2013 (this example predates the release of Adobe’s algorithm, but shows a similar result).

The result, although impressive, is far from what was expected and certainly from the original intention. [8]

Indeed, what is the problem?

When painting, the painter takes into account the flat surface of his medium. Through the use of materials (paints, pencils, hard or soft brushes, etc.), he translates what he perceives in three dimensions into a two-dimensional form. To do this, he takes into account the local color, but also its transformation by light. When trying to apply this painting to a volume, such as a person’s head, the conventions change: the homogeneous surface of flat paper is replaced by the surface of the volume, which is revealed by light.

[8] Jakub Fišer, Ondřej Jamriška, David Simons, Eli Shechtman, Jingwan Lu, Paul Asente, Michal Lukáč, and Daniel Sýkora, Example-Based Synthesis of Stylized Facial Animations In ACM Transactions on Graphics 36(4):155, 2017 (SIGGRAPH 2017, Los Angeles, USA, July 2017), ACM, U.S. Patent No. 10,504,267.

We thus witness a conflict between two approaches to lighting, which overlap without harmonizing: lighting integrated into the flat paint and lighting that reveals the volume of the head. This conflict results in a feeling of non-integration: we have the impression that the paint is applied to the face, rather than constituting a face in paint and in three dimensions.

Contours or structure?

Research into translating videos into a drawing “style” revealed similar cultural gaps. Engineers were unable to grasp how drawing works before designing their algorithm. Their device trained the algorithm, as usual, on databases composed of pencil strokes and fragments of lines, supposed to represent the “style” of different artists. [9] A sense of an artist’s “personal touch” certainly persists in the slightest trace they leave behind, but without taking into account what has been lost.

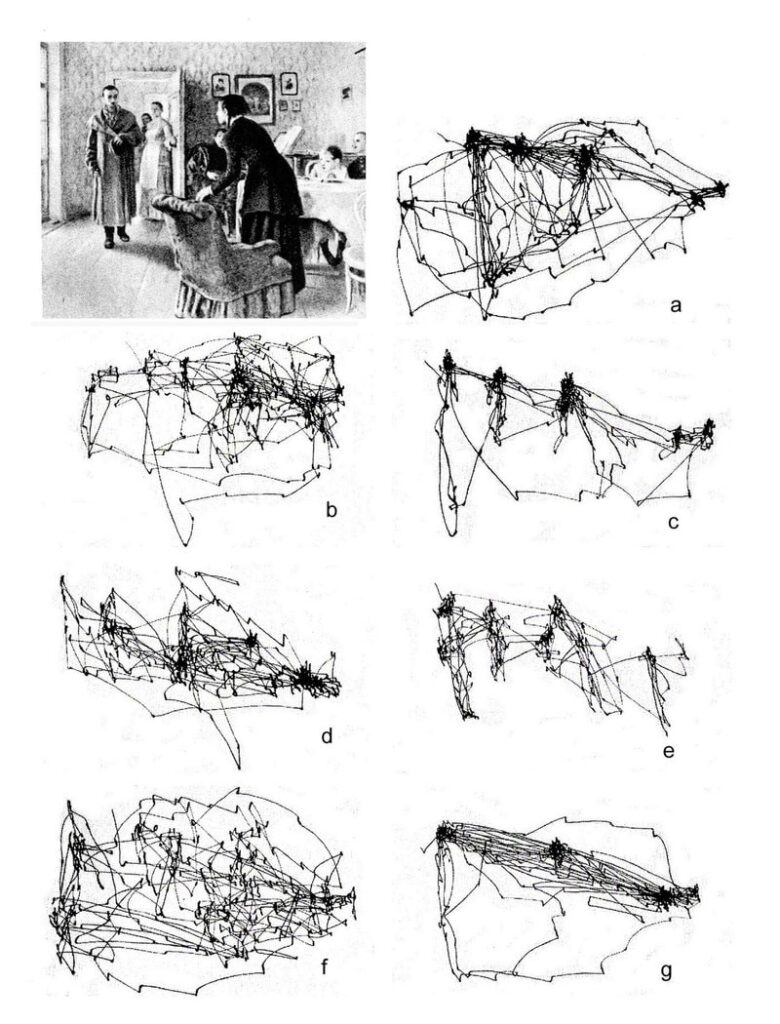

Beyond the scale, the “crumbs” of the artist’s strokes, a drawing bears witness to his gestures and his hierarchical gaze. Alfred Yarbus’s research [10] ont démontré que l’on ne regarde pas une scène toujours de la même façon, mais selon une approche qui cherche à répondre à des interrogations.

Similarly, an artist, consciously or unconsciously, emphasizes certain elements of their drawing, depending on the ideas that preoccupy them. A database consisting of drawings reduced to “bits and pieces” neglects this internal dynamic of drawing.

[9] Line-Drawing Video Stylization, N. Ben-Zvi1;2, J. Bento1;3, M. Mahler1, J. Hodgins1, A. Shamir1;4 Volume 0 (1981), Number 0 pp. 1–13 COMPUTER GRAPHICS forum. c 2015 The Author(s) Computer Graphics Forum c 2015 The Eurographics Association and John Wiley & Sons Ltd. Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd. faculty.runi.ac.il/arik/site/videosketch.asp

[10] A. L. Yarbus, Eye Movements and Vision. New York: Plenum Press, 1967.

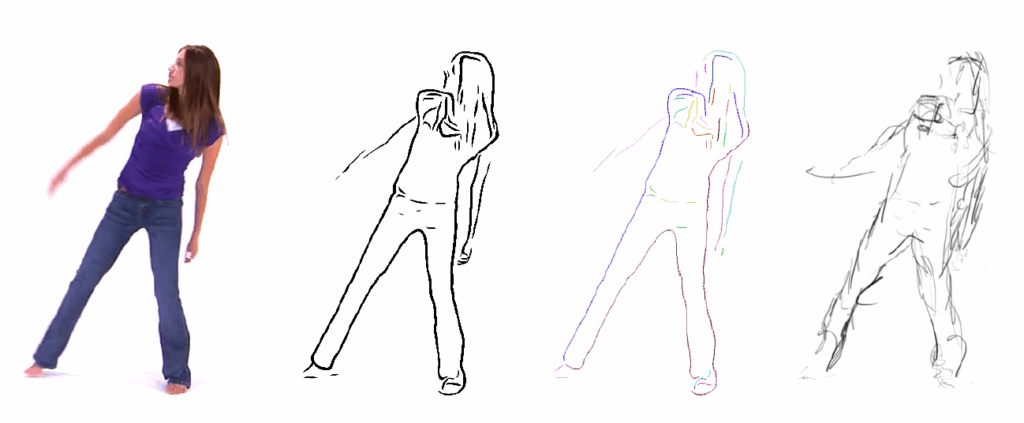

Once trained, the algorithms then identified the contours of figures from videos and proceeded to associate lines and contours, seeking to transform a video into a cartoon. However, the result gave the impression of watching magnetized “hairs” vibrating around an invisible, naturalistic figure of the dancer who had served as a model for the experiment. [11]

Indeed, when drawing, we first focus on the structure before seeking to render the details of the surface. In a quick sketch, especially with freehand lines, this is a characteristic approach. We refine the external parts as we identify the proportions and volume, and we gradually move forward by adding details. Each line reflects a gesture that interprets a vision, a feeling, provoked by the model and the mental process that triggers the gesture that creates the mark. This process is an essential component of drawing. By mechanically following the contours, we contradict the artist’s perception and mental functioning.

The arbitrary presence of a homogeneous outline, ignoring the fact that it varies depending on the light, compromises the result. This deviation becomes even more significant as the number of images used per second of animation increases. A high number of frames per second (25, for example) adds precision to the details and reveals the formal conflict between the design of the algorithm and the artist’s overall vision. This problem is well known in animation, particularly with the results of rotoscoping when tracing videos.

I let the artificial intelligence of the “Chat” draw its own conclusions:

Conclusion

«Artificial intelligence algorithms, often designed by computer engineers, reflect the skills and shortcomings of their training. Better integration of cultural and aesthetic aspects could enrich the results and avoid the pitfalls of mannerism and the loss of the history of forms.

Algorithms based on prompts and databases often reduce the expressive richness and internal dynamics of artistic works. By focusing on contours and surface features, they neglect the underlying structure and overall vision of the artist, which are essential to artistic creation.

Current approaches, by imposing conceptual and statistical models, risk transforming art into a “ready-made,” thereby impoverishing human creativity. To overcome these challenges, it is crucial to develop algorithms that integrate the historical and contextual vectors of artistic forms. Interdisciplinary collaboration between engineers, artists, and cultural specialists is essential to enrich databases and algorithm training processes.

By acknowledging the limitations of current approaches and seeking to integrate artistic sensibility, AI could open up new creative possibilities that respect the essence of art and human perception. This approach would preserve the emotional richness and depth of works of art while exploiting the technological potential of AI. »

My comment on the conclusion:

This summary highlights an optimistic view of the future possibilities of AI in the arts. “AI could open up new creative possibilities…” Certainly, it could. But my point of view in this text is neither pessimistic nor optimistic. It is education, a prerequisite for this AI (Le Chat, by Mistral), that leads it to draw conclusions in one direction. Vigilance is therefore required: the database terrain in which AI is trained is not neutral; it is also conditioned by ideologies.

20 février 2025