WRITING ANIMATION: PIERRE HÉBERT

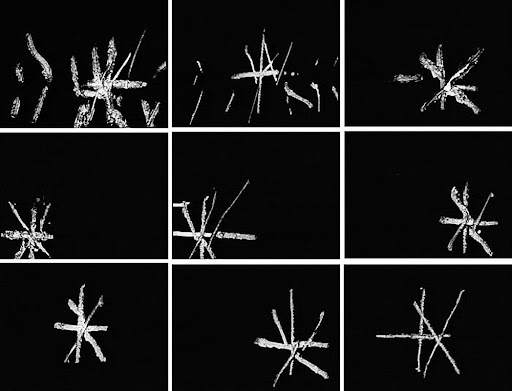

Georges Sifianos: We can start by talking about the raw material that you systematically use, i.e. the little signs that result from scratching and that could be called proto-writing. It refers to the tool, which scratches, it refers to the support, the film, and its resistance, it refers to the gesture, which can be precise or which can slip, and to the pressure exerted. Why did you fall in love with this way of doing things?

Pierre Hébert: You’ve described it very well. There are several aspects to it: the graphic nature of the lines engraved on film is very appealing to me. This raw, brutal, imprecise graphic style is full of energy and power. I’m interested in the imprecise nature of this work: we necessarily work frame by frame and, when it runs, there’s no absolute precision in the placement of the drawings from one frame to the next. I’ve always enjoyed seeing the succession of distinct images. The physicality, the pleasure of experimenting with the resistance of the emulsion and trying out different types of scraper. There’s an undeniable pleasure in the work and in the relationship with the tools and the material.

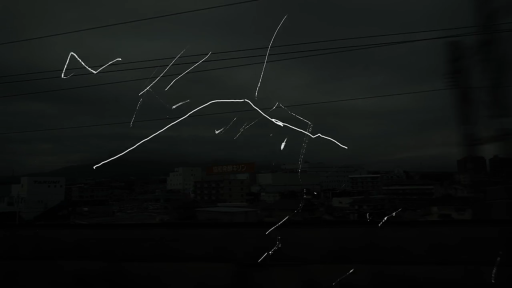

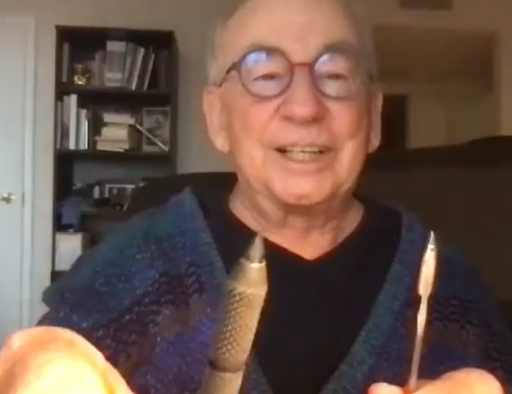

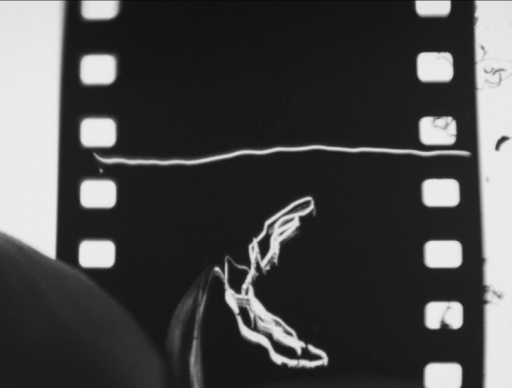

Le mont Fuji vu d’un train en marche, 2021

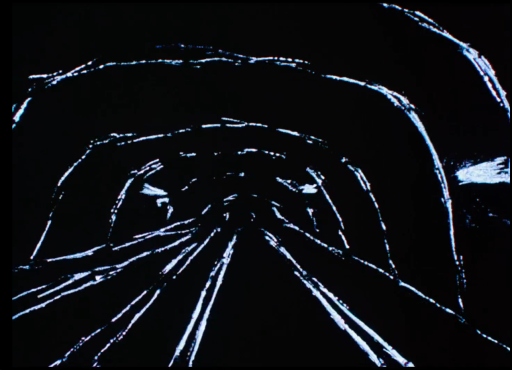

GS: From one film to the next, I see variations in approach within the same process. In Le mont Fuji vu d’un train en marche, the scratching is not exactly the same. Are these fleeting mental images at work in the film?

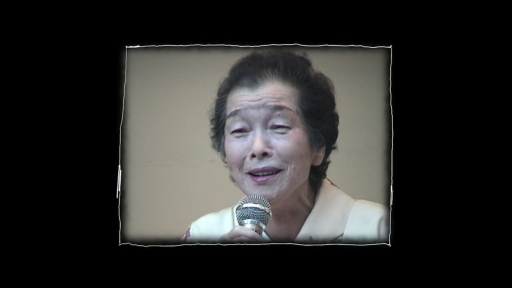

PH: What interested me in this film – and it’s a line of enquiry that I may still be following – was scratching in relation to words that I didn’t understand. The idea of proto-writing takes on its full meaning. It was a question of finding signs for words, for speech, recorded in public places in Japan, that I didn’t understand. You could compare it to Henri Michaux’s efforts to create fictitious alphabets by doing the opposite, i.e. starting from an oral expression and trying to add signs that correspond to it. The elements I could rely on were not the meaning of the words but the non-verbal dimension of language, i.e. intonation and fluidity. I have some animations in store for a film I started with a Vietnamese speaker.

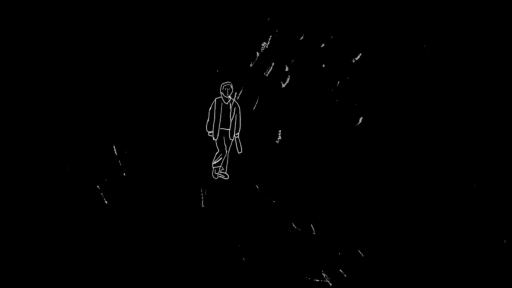

Le mont Fuji vu d’un train en marche, 2021

Zepe: What’s impressive about this film, compared to others, is the way in which these signs and features change from one situation to another. Each scene has a different, constantly evolving treatment. I saw these images in live action, interspersed with the graphic mapping, but in effect I was only following the narrative induced by the lines. This cryptography evolves in the film in a justified and powerful way, far surpassing anything I’ve ever seen in terms of engraving on film.

PH: I’m really pleased with your comment. I like the term cryptography, which I’d never thought of before. Thank you for suggesting it. I’m going to add it to my vocabulary. I don’t know how I came up with it, but it’s clear that in the making of the film there was a dynamic all of its own. I drew the different engraving segments on film in order, one after the other. There was no plan to achieve what you describe.

Le mont Fuji vu d’un train en marche, 2021

Zepe: It’s either a very intuitive approach, or the fruit of real logic. In the interview with Boris Labbé, the question of chaos is raised, and it seems to me that Pierre Hébert exploits it more than any other filmmaker. This random cryptography generates combinations that escape any form of pre-established composition, leaving great freedom to the appearance of features. The result is even a kind of persistence of vision, a parallel montage based on two different points of view evolving simultaneously, like two actions on the same screen.

PH: The first time I did live animation engraved on film was for a musical by Jean Derome, during which I interrupted the engraving and read texts. The show, inspired by the Orient, was called Confiture de Gagaku, based on Gagaku, a form of Japanese musical theatre. One of the texts, of Chinese origin, was called La mort du chaos (The Death of chaos). We presented these performances every day for a week and, at the end, I used the improvised segments to make a 15-minute montage, with which I envisaged making a film, without ever finishing it. The title of the film was La mort du chaos. This theme appeared in my performances right from the start.

Pochette du disque Confiture de Gagaku Jean Derome

GS: The death of chaos becomes the approach, the subject. How do you intend, or how have you done it in the past, to kill chaos, to organise chaos?

PH: With a point. Like these.

GS: I wasn’t speaking literally, I was thinking more in terms of modes of organisation. Looking at the films, I tried to list a certain number of motifs that you use – my list is incomplete, of course: the random dimension, the repetitive aspect, the aggressiveness of the scratch, sometimes the accumulation, the vibration, the evanescence, the parallelism of the strokes, the scratches, sometimes multiple, sometimes superficial, sometimes deep, the addition of colour, the circles, the straight lines, the presence/absence, the flashing, the displacement of the strokes or their fixity… The list is not closed.

PH: The combination of repetition and chance is decisive. The last performances I did, which I had to interrupt because of illness, consisted of working live on film with two projectors projecting at the same time onto the same screen. The two images were adjusted on the screen. I engraved alternately on the two projectors and the two loops were of slightly different lengths so that, through repetition, the adjustment between the two loops each time changed. The result was incalculable and uncontrollable. I can decide on the distribution between the two projectors of the type of strokes, and the type of patterns, but it’s impossible to control the encounters between the two streams – chance is inevitable.

Berlin – Le passage du temps, installation, 2014

The first time I used this process was with live footage shot in Berlin, in the video installation Berlin, le passage du temps (Berlin, the passage of time), I used four projectors simultaneously with four loops of different lengths. My son calculated that for these loops to return to the original diagram, the projectors would have to be left running for 1,000 years. To compose each of the strips and arrive at a form of organisation, I spread common thematic elements over the different strips, which thus have a greater probability of meeting and fitting together. In Berlin, le passage du temps, I distributed panoramic shots of the Berlin underground in one direction or another on each of the tapes, and regularly the same movements, in the same direction, appeared at the same time on all four screens. The work involved in distributing thematic elements to produce compositions that are not generated purely by chance is dizzying. Despite this effort, it continually eludes us.

Berlin – Le passage du temps, installation, 2014

Berlin – Le passage du temps, installation à la Cinémathèque québécoise, 2014

The repetitive sequence is fascinating: a 45-second loop and a 50-second loop recur continuously, but the composition produced varies all the time.

When Andrea Martignoni and I did the Scratch performance at the Louvre, I couldn’t find a way to end the projection, even though the two loops were sufficiently saturated by scratching, I was completely fascinated by observing the renewed combinations between the two loops. I made several attempts and Andrea and I would both sit in armchairs on the stage looking at the screen, letting our projectors roll on their own. I don’t think the audience really understood what we were trying to do.

Scratch, performance présentée à l’auditorium du Louvre avec Andrea Martignoni, le 14 octobre 2018

GS: Readers aren’t necessarily familiar with your work and what you describe is the culmination of an evolution. Can you describe your method of improvisation on the film loop that you scratch until the projector rips out the tape?

PH: There are several things that happen: firstly, the absence of control at different levels. I have to burn quickly because I know that the projector is going to rip the film out of my hands at some point and that puts pressure on me and the imprecision, the uncertainty from one image to the next is much greater than when burning on film in the studio. Then, to complete the loop in a reasonable time, I can’t wait and choose which part of the loop I’m going to continue to burn. As soon as the projector rips the film out of my hands, I have to immediately take the film where it is and burn it, so I burn a bit all over the loop and that produces a series of distinct segments, spread out along the length, which I will eventually splice together.

GS: How many metres of 16mm film do you work with in a loop?

PH: In metres, I don’t know, but it’s 50 seconds [NDR: 6 metres].

GS: It’s a long 50-second loop that runs permanently through a projector and you work on the free part until the projector rips the tape out and, at the same time, Andrea does the sound next to it in the same way.

Pierre Hébert et Andrea Martignoni à Area Sismica, Medola, 2009

PH: It’s conceptually very tight.

Andrea Martignoni: It makes the question of chance or the synchronisation of the audio part more complicated, because it might work very well with an image but then never again. The sound is created more quickly than Pierre obviously does, it doesn’t have to be figurative.

PH: The sound loop adds an element of chance; the three loops roll independently and combine in unpredictable ways.

GS: Do you ever try to introduce a narrative dimension?

PH: In the case of the performances with two projectors, there isn’t really a narrative element. But the performances I did with the musician Bob Ostertag included a thematic element imposed by the very material Bob used for his music. I would prepare small, more narrative segments of animation in advance. I would then stop the projector at certain points and paste these segments into the loop.

Colleuse 16 mm

GS: In Mais un oiseau ne chantait pas, you limit yourself to a specific length of time. What criteria did you use to set the duration?

PH: It’s determined by the music of Malcolm Golstein, whose violin work I find close to the texture of etching on film. After a performance and video installation with him, I decided to make a film based on a piece I really liked, Mais un oiseau ne chantait pas, But one bird sang not.

GS: I’m actually impressed by the sonic and visual match between the sound timbres and the engraved forms.

PH: In this case, I did something I don’t normally agree with, I did some extreme mickeymousing, starting from a very precise and detailed analysis of the music to which I adjusted the animation. I usually avoid this process because I feel that time does not flow in the same way in music and images and that this way of constraining the image to a precise musical organisation does not seem right to me. In this case, the very nature of Malcolm’s music allowed me to do it, but it’s a special case.

But one bird sang not, 2018

GS: In Le mont Fuji vu d’un train en marche, the singer’s hoarse voice has a similar match with the scratching.

PH: In that case too, I analysed the sound, but not everything in the film is analysed in the same way. Some passages are left to chance. And even though I don’t fundamentally agree with this process of matching, I find a certain pleasure in doing it.

Le mont Fuji vu d’un train en marche, 2021

Éthann Néon: What makes you say that musical and visual time, within an audiovisual work, are not in harmony and do not flow in the same way?

PH: Of course it’s possible to synchronise them, but I find, for example, that the value of repetition in music is not at all the same as the value of repetition in film. It’s much more restrictive and difficult to use repetition in film, whereas it’s natural in music.

Éthann Néon: And yet the loop is a common process in animation.

PH: Absolutely.

EN: Repetition is inherent in the language of animation and from that point of view animation is similar to certain musical repetitions, which is not the case in live-action cinema. In perceptive terms, you make a very clear distinction between the two. As far as I’m concerned, it depends very much from one work to another.

PH: It goes back a long way, when I started out in the early 60s, I was interested in the idea of visual music, which I eventually broke away from. I tried to animate a waltz using images alone and no matter how much I tried to distribute the accents visually, it never gave the feeling of a waltz as played by a musician. I then came to the idea that the value of the passage of time in animation, and the possibility of distributing accents and creating a certain effect, was radically different from music. I don’t know whether this experiment led to a convincing conclusion, but afterwards it was a determining factor for me, an idea that has always been present in my work. I have, however, taken great pleasure in synchronising images and sound on occasion, as in Mais un oiseau ne chantait pas, so what I say is worth what it’s worth, it’s not necessarily the truth.

Op Hop – Hop op, 1966

For the film Le métro (The Underground), I took a photograph of a man and his child in the Underground and asked myself the question of the gaze. How do you animate a still gaze and get the feeling of that gaze? So I repeated this image of the man and his child in a number of frames and applied to this series of drawings a formula that I called the staggered cycle. I printed the image from 1 to 10, then from 2 to 11, then from 3 to 12, then from 4 to 13 and so on, on the truca [a machine used to create effects in the laboratory], thinking that this would create a mixture of order and disorder that can exist in a look. It wasn’t really convincing as far as the look was concerned, but the staggered repetition that created a double rhythmic structure really interested me. The break between the sequence from 1 to 10 and then from 2 to 11 was very marked. This created an initial rhythmic structure based on ten. In addition, the recurrence of each of the images that made up the series was shorter, by one image, and shorter (9) than the temporality created by the break in the loop. A rhythm of nine opposed to a rhythm of ten. It was this shifted rhythmic structure that served as the basis for the first version of the performance software that Bob Ostertag created for me. Ultimately, this is also where the idea came from to link loops of different lengths together in my video installations and in my performances with two projectors.

Chants et danses du monde inanimé – Le métro, 1985

When my colleague Bob Ostertag programmed my image processing software, he derived it from his own digital sampling software in which there was a highly developed and complex loop system. The use of digital technology increased the possibilities of creating different types of loops, easily changing the starting and ending points of loops and creating very subtle variations. As a result, I’ve been experimenting a lot with loops, which eventually led to the idea of two-projector performances.

Special forces, performance de Bob Ostertag et Pierre Hébert à Roulette, New York, 27 mars 2008

GS: At the same time, with digital, the sensuality of the film material disappears.

PH: Yes, it was a tragedy in my life when Bob created this software. It meant that the images recorded on film had to be captured with a camera, which was impossible or very laborious. I made a few attempts to digitise the images on film but there was no way of digitising them quickly enough to fit into this process where speed was of the essence. I thought I’d just given up engraving on film. I necessarily had to move on to animating objects and painting on glass to feed the process and respond to the pressure of these performances. At the start, there are no images and the accumulation of images, the speed of the accumulation of images is an important element. But you also have to manage the composition of these images using the software and continually change the parameters for processing the images, the length of the loops, the colours and the superimpositions. I was torn between the two: making images as quickly as possible and, on the other hand, intervening on the computer to organise them. It’s similar to the pressure created in live film-engraving performances with a projector. For the painting on glass, I looked for tools, brushes or objects that were too big for the surface I was working on, in an attempt to recapture the graphic force of etching on film. My son, who is a programmer, revised and transformed Bob’s software so that it could be used with a phone and a tablet to control the computer’s functions, which was much more direct than using the computer keyboard. After several years of performing with the digital tool, I tried to reintroduce engraved images and I realised that I had lost the physical link with this practice and it took years before I found it again. What happened was that Andrea and I started doing performances, initially called Digital scratch, in which I would simultaneously do the digital work and the printmaking on film. At first I realised I’d lost my skill, but doing the show inspired by Norman McLaren’s Blinkity blank in 2015 at the Cinémathèque Québécoise, I felt like I’d rediscovered the link.

Digital Scratch à Poznan avec Andrea Martignoni le 14 juillet 2012

Ballade sur Blinkity Blank, 2014

AM: I recently prepared a masterclass based on the work I’ve done with Blu and the work I’ve done with Pierre. If you look at his website, which covers 60 years of his career, the collaboration between us only represents 10%.

PH: Andrea’s knowledge of my work is exceptional. I remember a masterclass in Sicily where Andrea was translating what I was saying into Italian for the students and I realised that he was adding a lot of information that anticipated what I was going to say at the time of translation!

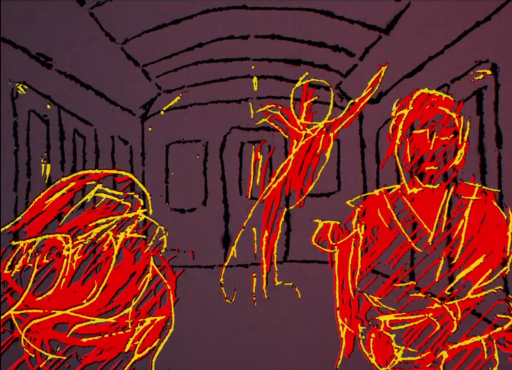

EN: You said that the move to digital, in terms of performance, had changed your way of working live, but in the films made with video, whether it’s La statue de Robert E. Lee à Charlottesville or Le mont Fuji vu d’un train en marche, there’s a different kind of writing compared to scratching on film, with a kind of rotoscoping and cropping of shapes.

PH: I had already cut out shapes by scratching an interpositive taken from a live-action shoot, like at the start of my feature film La plante humaine (The human plant). It was a bit laborious because the engraving on the interpositive produced chips of emulsion and, even if you cleaned the interpositive before developing a new negative, there were still residues of emulsion on the film and the result wasn’t clear, to which we can add the deterioration of the image caused by going from the original negative to the interpositive and then to a new negative. When I started shooting digitally for the Lieux et monuments series, I quickly acquired a Cintiq tablet, which gives me a great deal of precision without any loss of quality. Trimming in white every two images is close to the dynamics of engraving on film.

La plante humaine, 1996

EN: It’s not really a rotoscopy in the sense that rotoscopy generally doesn’t reveal the original medium and produces a new image. Clipping gives you the opportunity to catch our eye on a particular element.

PH: It’s part of a more complex context. Most of the shoots in the Lieux et monuments series took place with a fixed camera, on a tripod, with the aim of altering the real image itself, there’s a temporal reassembly of the events that occur in the image, like a sort of jigsaw puzzle, by cutting up the real image into different sections that I could recompose and change the place of the events. Trimming is part of a process of intervening in the live-action shoot with the aim of reconfiguring and re-choreographing it.

La plante humaine, 1996

GS: In Le mont Fuji vu d’un train en marche, the director’s presence is assertive, as he selects and picks with the subjectivity of his gaze. Not all the figures are identified. It could be a challenge to photographic representation that is rectified, or it could be a marriage of the resonances and vibrations of different modes of figuration, or it could simply be a feeling for which no explanation need be sought, or this vibrant outline could be the result of the debunking of individuals as in La statue de Robert E. Lee à Charlottesville (The Statue of Robert E. Lee in Charlottesville), which deals with the subject of debunking. The viewer can come up with any number of interpretations. What part do you play in raising awareness of these issues?

PH: It’s a bit like all that really, you can guess the ideas that are in my head. Your hypotheses are very accurate.

AM: In the middle of your career, in the 70s and 80s, you worked on documentaries by other directors, and the Lieux et monuments series is a return to that.

PH: Yes indeed, I worked with a number of directors on their films, in particular the films of Fernand Bélanger, which led to Love addict, based on one of his films.

Love Addict (Offenbach), avec Fernand Bélanger, 1985

AM: In these collaborations, is it a question of underlining or erasing something?

PH: In the case of Fernand’s films, the idea was to superimpose a second discourse on his editing. I chose thematic elements that were in line with the film but I reorganised them. The one-off contributions were spread evenly throughout the film, creating a continuity as if two films were being shown at the same time, one a commentary on the other.

In 2021, a symposium was organised in Paris on the work of Robert Lapoujade, a painter and experimental filmmaker from the early 1960s who worked in the research department of ORTF. One of his films made a big impression on me at the time: Prison. To prepare for this conference, Pascal Vimenet asked me if I wanted to do something related to Lapoujade. I made a film called Palimpseste sur Prison de Robert Lapoujade (Palimpseste sur Prison by Robert Lapoujade), which consists of Lapoujade’s film in its entirety and a film-commentary that adds to it without obliterating Lapoujade’s film.

Palimpseste sur Prison de Robert Lapoujade, 2021

GS: You’re also an animation theorist. To what extent do the two activities interact or not?

PH: I’ve often wondered what I was trying to achieve by writing. The two activities are in tension. The first objective is to understand what I’ve done, a commentary on previous work, while at the same time trying to be open and define what I should do next. A tension between the past and the future, never one or the other, in the knowledge that I won’t be able to fully explain what I’ve done or devise a plan that I’m going to follow. From this point of view, I distance myself from the creative work, because when I take on a new project, I never do exactly what I was able to work out when I was writing. It always takes a different direction. It’s a vital, essential activity for me.

L’ange et l’automate, Les 400 coups, 1999

Corps, langage, technologie, Les 400 coups, 2006

GS: Between a performance, a short film and a feature film, the operating methods are not necessarily the same. How did you prepare Le mont Fuji vu d’un train en marche? How much of it was improvised? Because it’s a production with a journey to plan, with a team, to achieve a result you didn’t know about in advance.

PH: No, there was no script.

There was no team with me. It was a no-budget production. I got a grant for this calligraphy course in Japan, which covered the costs.

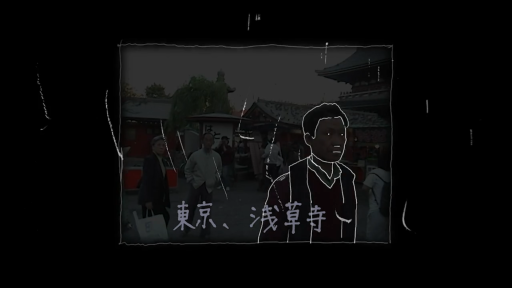

Unlike Mais un oiseau ne chantait pas, which has a fixed duration, the material was made up of all the experiences I had during the two months I spent in Japan, including travelling and filming in various places, including Nagasaki, workshops with the dancer Teita Iwabuchi, the performance at Koji Yamamura’s animation school and the calligraphy classes.

GS: You were in Japan initially for another reason and then you had the idea of collecting this material. Did you scratch the images on your return?

PH: Yes. I used a zoom recorder or an iPhone without worrying about the quality of the images and sounds. The important thing was to pick up traces of this experience that I hoped to do something with.

I shot images thinking that they could become a film, like, for example, the still shot of the main square in Nagasaki, which I thought I’d include in the Lieux et monuments series.

Then, while waiting in the café at Mishima station, I was struck by the different layers of sound, the neighbours chatting, the waitresses in the distance, the background music, and the roar of the Shinkansen trains passing by every few minutes, and I decided to record all this with the idea of making animation from these elements. When I got back, that was the first sequence I animated, which consisted of finding signs for words whose meaning I didn’t understand.

After the trip, I continued to record sounds in the hope that they would be useful, like the prayers and drumming in temples on New Year’s Eve.

I quickly put together a set, not determined by a scenario or precise planning, but by a balance in terms of duration.

Le mont Fuji vu d’un train en marche, à Nagasaki, 2021

GS: We can imagine that you now have a lot of documents collected and unused.

PH: Absolutely, particularly in Vietnam. And from all over the world. When Bob Ostertag and I were doing performances all over the world, I quickly began to accumulate material, mainly actual filming, and sound too, so I have a fairly large catalogue of footage from all over the world.

GS: How do your films, which are not ordinary or big-budget, circulate?

PH: All the films produced by the National Film Board of Canada are its property and are distributed by the NFB.

After I left the NFB at the end of 1999, I quickly got in touch with a video artists’ centre in Montreal called Vidéographe, which does distribution and used to specialise in video art, but which has started to distribute films like mine. It’s not massive distribution but occasional distribution. I regularly put together programmes of my films, particularly those in the Lieux et monuments series.

When I started doing performances, one of my aims was to have a more direct relationship with the public. The way films are shown in cinemas is impersonal and the audience obviously didn’t come to see the short film but rather the feature film it accompanied. I was quite disappointed by this form of distribution. Direct contact with the audience creates a context over which I have a certain amount of control, unlike when short films are shown as the first part of feature films in commercial cinemas.

Scratch, performance présentée à l’auditorium du Louvre, le 14 octobre 2018

GS: McLaren said that he became an animator because he liked to dance, but he was quite shy. As far as you’re concerned, you like the pressure of being on stage, with the tension induced by the fact that the camera rips the film off you. Do you feel more like an actor than a filmmaker?

PH: Perhaps yes, in particular the mixed digital and film etching performances I did with Andrea reinforced this because they required me to move from one workstation to another during the performance. This was an element of spectacle for the audience, who saw me running every five minutes from the computer to the projector and back again.

There was also the risk that the film might break or get tangled up; this apparently perilous aspect of live film engraving was almost a circus-like performance, which is why I always insisted on being in front of or in the middle of the room, and certainly not behind it, so that the spectators could see me as well as the projected image. Len Lye had described his work on Free Radicals as a dance.

GS: One of my students wrote a dissertation and examined Free radicals frame by frame (Denis Rousseau, 2004). He spotted the existence of small, almost invisible dots, from which he drew lines. He demonstrated that there was a repertoire of signs that Len Lye repeated by rotating them. Len Lye thus created a mythology about the fact that he danced…

Free radicals de Len Lye

PH: Some people who saw him animate have likened it to a dance, in connection with his idea of synesthesia, of the inner sense of movement that he talked about during an interview I had with him in Montreal in the early 60s.

In his animations, the shapes rotate in a controlled way, so it’s probably not just left to chance. Still, I like the idea that it was a dance and that the signs on the image were the result not just of the movement of his hand but of the movement of his whole body. Hence the idea of the dance.

GS: He acts as a dancer but not just as an improviser, he codifies beforehand.

Vincent Gilot: In your work, the scratching on the film is very free, with a series of small signs scattered across the image, whereas we’re used to large verticals, like curtains crossing. When there are lines in your work, they are more horizontal than vertical. McLaren had a prism built that allowed him to project the previous image and make drawings on film with the previous drawings. Is it a choice in your work that the images are distinct and unconnected with the image before and the image after?

PH: In my first film, Histoire grise ou Histoire verte, depending on which era you’re referring to, I drew large vertical lines like McLaren, but I quickly moved away from them because I wanted it to be really frame-by-frame animation and for each frame to be very distinct from the previous or subsequent ones. However, it stems from an idea that McLaren had in the series of didactic films he made about animated movement towards the end of his life. In them he talks about muscle memory, in other words the possibility of remembering the movement made to draw the previous image by the memory of the arm and hand that remember the previous gesture. This is not far removed from Len Lye’s idea of synaesthesia. This idea has stayed with me a great deal and has led me to exercise both my eye and my hand in an attempt to master the sequence of images.

Histoire grise ou Histoire verte, 1962 & 2005

In Souvenir de guerre, I used layers to place dots on the film. I drew strips of film on paper, photocopied them, cut them out, placed the film under the paper, aligned it with the drawn film and this enabled me to inscribe dots on the paper and transfer them to the film itself. This produced the highly narrative, not at all abstract, animation of Souvenir de guerre. I used this technique in several other films from this period. But I abandoned it because it killed the spontaneity and graphic force of the engraved lines. This observation led me to performance art, where, by placing myself in a dangerous situation under pressure, I developed a form of precision that did not depend on external means – such as transferring dots onto the film – but was essentially based on the memory of my eyes, hands and arms, the previous gesture and the spontaneous ability to judge the place in the black frame where I had drawn the previous image. It was a radical decision to abandon all forms of artificial location-finding methods.

Souvenirs de guerre, 1982

VG: Does this radical approach extend to the point of never replaying the film to correct what has been recorded?

PH: Indeed, I don’t correct. That’s what led me to train in calligraphy. What film engraving and calligraphy have in common is that you never correct, what is drawn is drawn. I can throw away the sheet of paper or the piece of film but I don’t correct it.

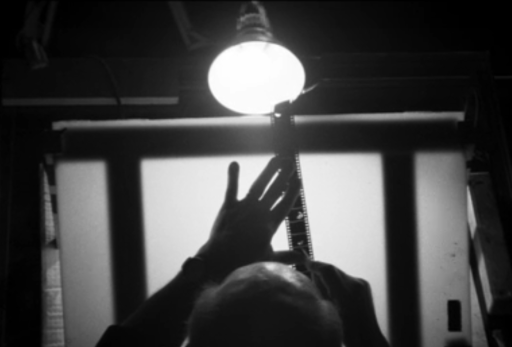

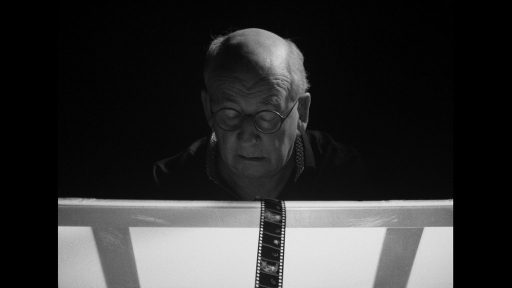

Scratches of Life: The Art of Pierre Hébert de Loïc Darses, 2024

GS: Did Japanese calligraphy inspire you formally?

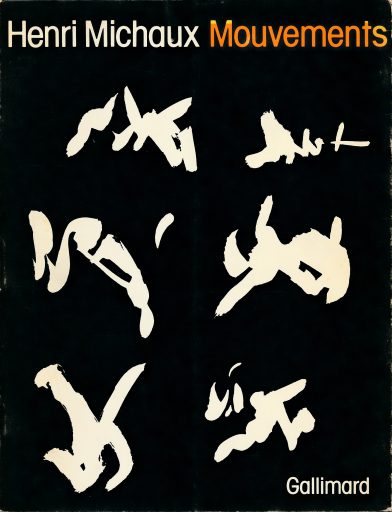

PH: I wasn’t directly influenced by the type of line in calligraphy, with its full and loose strokes. I came very close to the work of Henri Michaux, who himself referred to calligraphy on a conceptual level, as in his book Mouvements, where he proceeded by signs. His work was already important to me, but it became even more so after this experience.

After the live film engraving performance in Tokyo at Koji Yamamura’s school, my wife told me that she had seen an influence of his calligraphic work that day.

Mouvements de Henri Michaux, Gallimard, 1952

GS: You draw differently with coloured pencils in your book of portraits, which could take your work elsewhere.

PH: One of the avenues I’ve been exploring recently is freeze-framing animation on film. It shows things that you can’t see when the images are running. I make a drawing on the frozen image, a drawing modelled on this image, it’s like making two successive folds of the image: a first fold by stopping the engraving on film and a second by transferring it to a drawing made using other means.

GS: You use this process in Le mont Fuji vu d’un train en marche, with freeze-frames on engraved pictograms and other engravings moving over them.

PH: I actually started with that film.

GS: You told me that in some way the scratching on film came from your former interest in archaeology and excavations…

PH: Yes, it’s the same gesture of scratching to uncover something hidden. I like to think that was an important starting point. And the influence of McLaren and Len Lye, which was ultimately more decisive, was grafted onto this initial fantasy of the archaeological dig. Hence the dual reference to calligraphy and cave paintings, which has remained with me to this day. A double reference that I also found in Henri Michaux, who over the years has been another increasingly significant influence. Even though he wasn’t an animator, he nevertheless did a lot of serial drawings, as in his book Mouvement. I asked myself a lot about what linked these successive drawings, which were ultimately an invitation to explore discontinuity and to rely on a form of succession that isn’t necessarily expressed in terms of explicit, perceptible movements. ‘Movements in place of other movements that cannot be shown but which inhabit the mind’, as Michaux wrote.