THE DEFINITION OF ANIMATION, A LETTER FROM NORMAN MCLAREN

Georges Sifianos

In 1986, when I was writing my doctoral thesis on the subject of ‘Language and aesthetics of animated film’, I spent a lot of time trying to understand in depth the meaning of the term ‘animation’. Definitions existed, but they weren’t always satisfactory. In most cases, the main problem was that people tried to define this cinema in terms of its techniques, whereas identical results could be obtained using a variety of techniques. There were no clear boundaries. If, for example, we take the classic definition of animated cinema, ‘frame by frame cinema’, it very quickly proves to be limited, as we can see if we film an immobile element, a wall for example, at different frame rates: at 300 frames per second, at 24 frames per second or frame by frame: the result remains identical.

For me, the property of animation was not inherent in an object, but was attributed to it. This quality depended more on the era, the culture and the historical period, than on the technique.

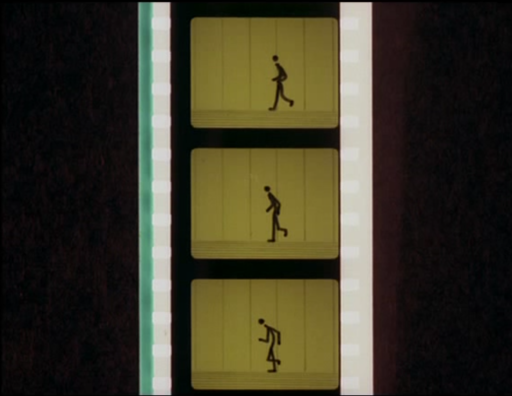

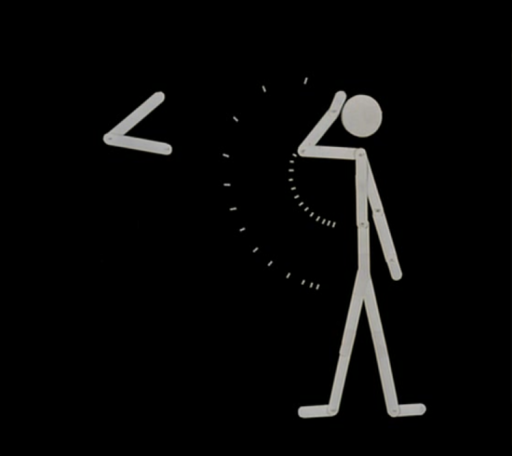

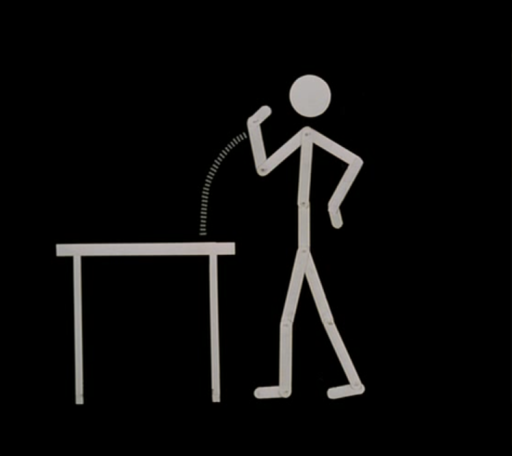

Animated motion by Norman McLaren & Grant Munro (1976)

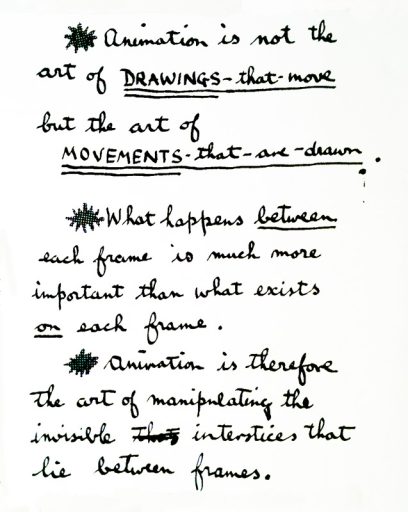

One of the best-known definitions of animation was that of Norman McLaren, who made the following three statements [1]:

- “Animation is not the art of DRAWINGS-that-move but the art of MOVEMENTS-that-are-drawn.

- What happens between each frame is much more important than what exists on each frame.

- Animation is therefore the art of manipulating the invisible interstices that lie between frames.»

I had noticed on many occasions that the desire to enhance the status of a cinema unfairly considered as ‘children’s cinema’ led to the adoption of impressive but questionable ideas. I wondered whether Norman McLaren’s enigmatic definition did not also create a mythology for animated cinema (the expression ‘the art of manipulating invisible interstices’ suggested the idea of a magical power…). Different translations of McLaren’s definition developed the metaphysical dimension further, which made me curious about what he meant exactly. [2]

Animated motion by Norman McLaren & Grant Munro (1976)

Various answers had already been given to the question of how to ‘draw’ movement: for example, Géricault, in his painting ‘The Epsom Derby’, combines two different moments in a horse’s gallop to create a sensation of movement. The Futurists’ solution was to multiply the number of legs of an animal, for example, in a given painting. But what was McLaren’s point of view? What did he mean by ‘drawn movements’? Was his expression literal or figurative? Literally, movement cannot be drawn. Metaphorically, the meaning wasn’t clear either. On the other hand, I wondered why ‘what happens between the images’ was so important. If it had value for a scientist, how could it be valid for an artist whose work appears on each photogram? Why are the images on the photograms less important?

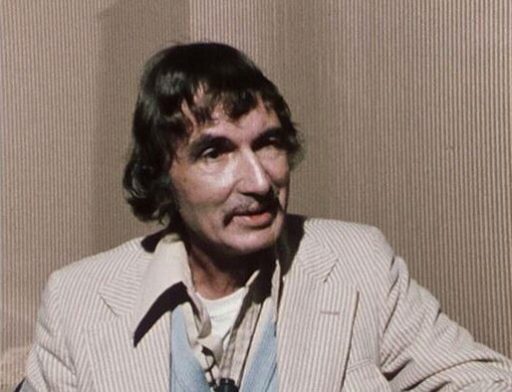

Of course, I understood that McLaren, as an animator, preferred movement to static images. However, I had questions about his definition of animation, so I wrote to him to ask for clarification. Below is the letter I received in response to my questions, in which McLaren modifies his initial definition.[3]

[back to text]

[2] André Martin, for example, translates ‘what happens’ between each photogram as ‘what there is’, which is far from McLaren’s thinking. A similar translation can be found in Cinéma 57 14 (1957).

[back to text]

[3] Extracts from this letter were published for the first time in English in the magazine « Animation journal, Spring 1995 » and on several subsequent occasions. The letter in its entirety is also published in my book Esthétique du cinéma d’animation, Paris, Cerf-Corlet, 2012.

[back to text]

Animated motion by Norman McLaren & Grant Munro (1976)

THE LETTER FROM NORMAN MCLAREN

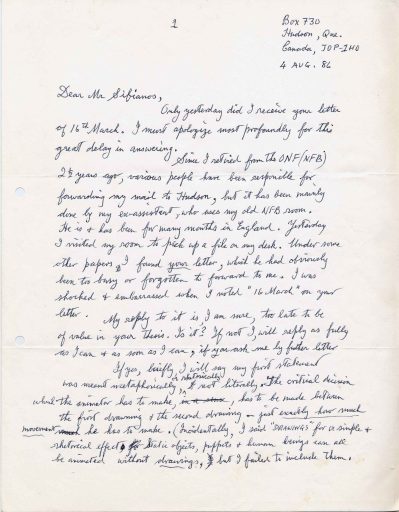

1

Box 730

Hudson, Que.

Canada, JOP-1H0

4 AUG. 86

Dear Mr Sifianos,

Only yesterday did I receive your letter of 16th March. I must apologize most profoundly for this great delay in answering.

Since I retired from the ONF (NFB) 2 ½ years ago, various people have been responsible for forwarding my mail to Hudson, but it has been mainly done by my ex-assistant, who uses my old NFB room. He is and has been for many months in England. Yesterday I visited my room to pick up a file on my desk. Under some other papers I found your letter, which he had obviously been too busy or forgotten to forward to me. I was shocked and embarrassed when I noted “16 March” on your letter.

My reply to it is, I am sure, too late to be of value in your thesis. Is it ? If not I will reply as fully as I can and as soon as I can, if you ask me by further letter.

Animated motion by Norman McLaren & Grant Munro (1976)

If yes, briefly I will say my first statement was meant metaphorically or rhetorically, not literally. The critical decision which the animator has to make has to be made between the first drawing and the second drawing – just exactly how much movement he has to make (incidentally, I said “DRAWING” for a simple and rhetorical effect. Static objects, puppets and human beings can all be animated without drawings, but I failed to include them.

Animated motion by Norman McLaren & Grant Munro (1976)

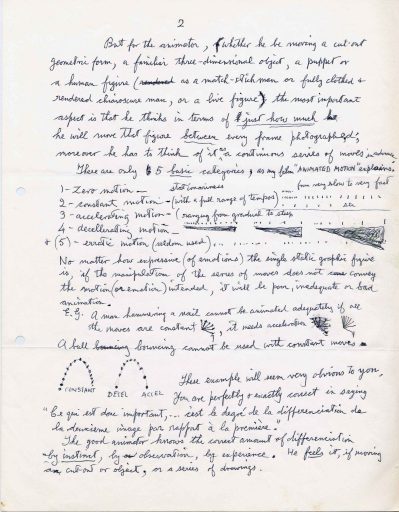

2

But for the animator, whether he be moving a cut-out geometric form, a familiar three-dimensional object, a puppet or a human figure (as a match-stickman or fully clothed and rendered chiaroscuro man, or a live figure) the most important aspects is that he thinks in terms of just how much he will move that figure between every frame photographed, moreover he has to think of it as a continuous series of moves in advance.

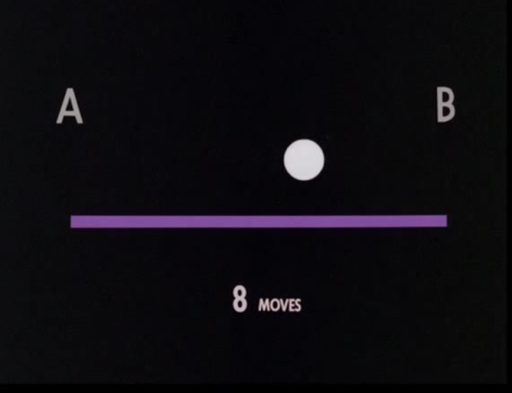

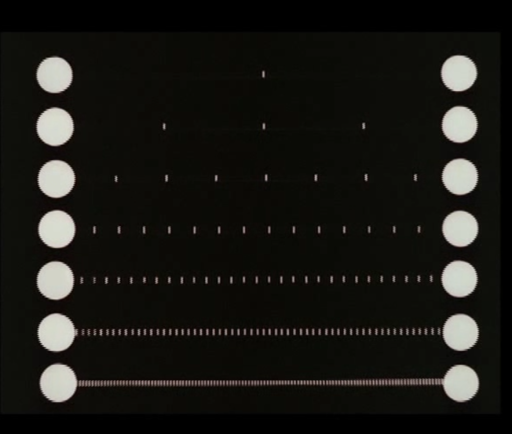

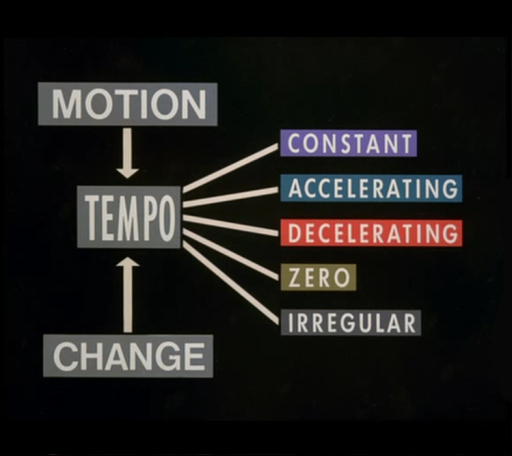

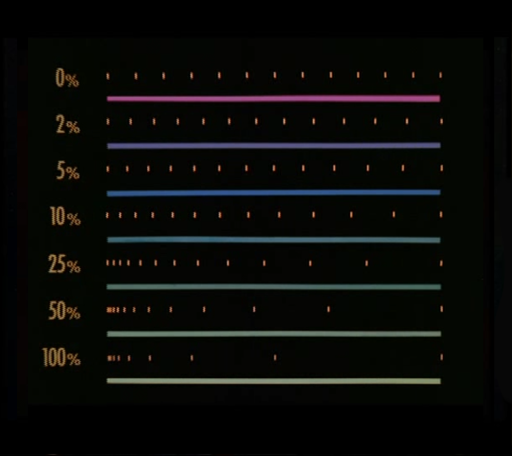

There are only 5 basic categories, as my film “ANIMATED MOTION” explains:

1 – zero motion – stationariness

2 – constant motion – (with a full range of tempos)

3 – accelerating motion – ranging from gradual steps – from very slow to very fast

4 – decelerating motion

5 – erratic motion (seldom used)

Animated motion by Norman McLaren & Grant Munro (1976)

No matter how expressive (of emotions) the single static graphic figure is, if the manipulation of the series of moves does not convey the motion (or emotion) intended, it will be poor or bad animation.

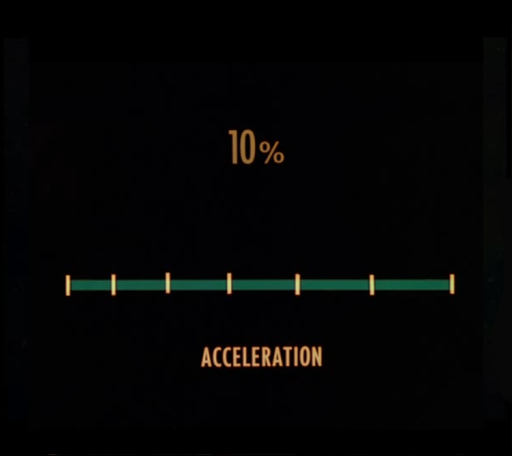

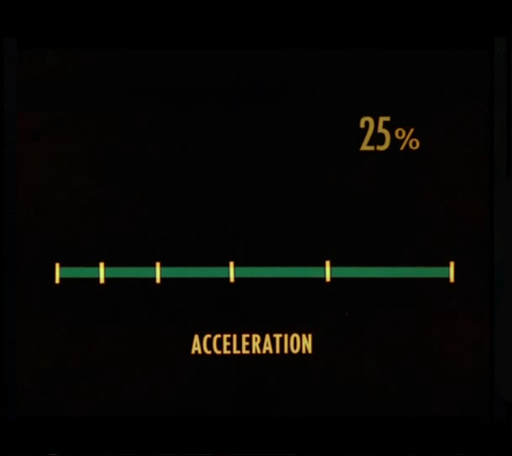

E.G. A man hammering a nail cannot be animated adequately if all moves are constant, it needs acceleration.

A bull bouncing cannot be used with constant moves.

CONSTANT DECEL ACCEL

Animated motion by Norman McLaren & Grant Munro (1976)

These examples will seem very obvious to you. You are perfectly and exactly correct in saying “Ce qui est donc important, … c’est le degré de la différenciation de la deuxième image par rapport à la première”.

The good animator knows the correct amount of differentiation by instinct, by observation, by experience. he feels it, if moving a cut-out or object, or a series of drawings.

Animated motion by Norman McLaren & Grant Munro (1976)

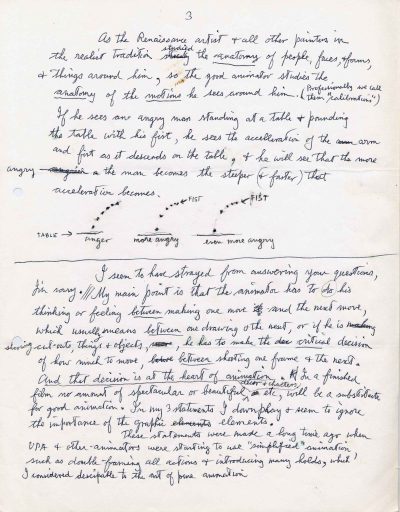

3

As the Renaissance artist and all painters in the realist tradition studied the anatomy of people, faces, forms and things around him, so the good animator studies the anatomy of the motions he sees around him (professionally we call them “calibrations”).

If he sees an angry man standing at a table and pounding the table with his fist, he sees the acceleration of the arm and fist as it descends on the table, and he will see that more the man becomes the steeper (and faster) that acceleration becomes.

TABLE > anger more angry even more angry

Animated motion by Norman McLaren & Grant Munro (1976)

I seem to have strayed from answering your questions, I’m sorry. /// My main point is that the animator has to do his thinking or feeling between making one move ad the next move, which usually means between one drawing and the next, or if he is shooting cut-outs, things and objects, he has to make the critical decision of how much to move, between shooting one frame and the next. And that decision is at the heart of animation. In a finished film no amount of spectacular or beautiful decor and characters, etc., will be a substitute for good animation. In my 3 statements I downplay and seem to ignore the importance of the graphic elements.

These statements were made a long time ago when UPA and other animators were starting to use “simplified” animation, such as double-framing all actions and introducing many holds, which I considered despicable to the art of animation.

United Productions of America (UPA)

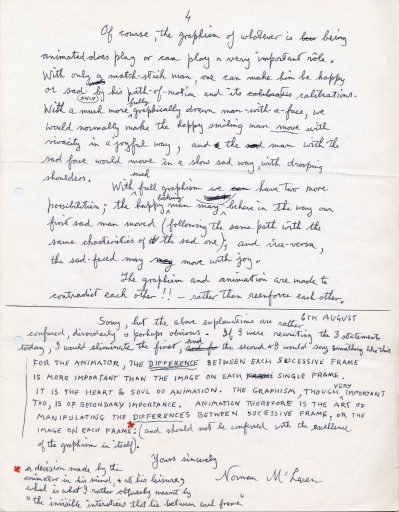

4

Of course, the graphism of whatever is being animated does play or can play a very important rôle. With only a match-stick man? one can make him happy or sad ONLY by his path-of-motion and its calibrations. With a much more fully graphically drawn man-with-a-face, we would normally make the happy smiling man move with vivacity in a joyful way, and the man with the sad face would move in a slow sad way, with drooping shoulders.

With such full graphism we have two move possibilities; the happy looking man behave in the way our first sad man moved (following the same path with the same characteristics of the sad one); and vice-versa, the sad-faced may move with joy.

The graphism and animation are made to contradict each other!! – rather than reenforce each other.

6th AUGUST

Sorry, but the above explanations are rather confused, disorderly and perhaps obvious. If I were rewriting the 3 statements today, I would eliminate the first and the second and I would say something like this

FOR THE ANIMATOR, THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN EACH SUCCESSIVE FRAME IS MORE IMPORTANT THAN THE IMAGE ON ACH SINGLE FRAME. iT IS THE HEART AND SOUL OF ANIMATION. THE GRAPHISM, THOUGH VERY IMPORTANT TOO, IS OF SECONDARY IMPORTANCE. ANIMATION THEREFORE IS THE ART OF MANIPULATING THE DIFFERENCES BETWEEN SUCCESSIVE FRAME, OR THE IMAGE ON EACH FRAME*: (and should not be confused with the excellence of the graphism itself).

Yours sincerely

Norman McLaren

* a decision made by the animator in his mind, and at his leisure, which is what I rather obtusely meant by “the invisible interstices that lie between each frame”.

Norman McLaren died on 26 January 1987.

Click to enlarge.